What Can We Learn from Michigan?

A state with well established school choice programs has a lot to teach us about the future of K-12 education.

In February 2017, if you turned on your TV to any news station or scrolled through your Facebook newsfeed, you saw the polarizing appointment of Betsy DeVos as the 11th U.S. Secretary of Education. For many K-12 leaders, this nomination was alarming.

Usually, these appointments fly under the political radar. However, due to DeVos’s lack of education experience and pro-school-choice work in Michigan, she was faced with a barrage of heated questions in her confirmation hearing. When asked if she was committed to protecting public schools, she said:

“Not all schools are working for the students that are assigned to them ... We can solve those issues and empower parents to make choices on behalf of their children that are right for them."

The message was clear. A major priority for the DeVos Department of Education would be to spread school choice across the country.

It’s no surprise that Michigan, DeVos’s home state, has a history of school choice. DeVos and other wealthy donors have donated millions of dollars to influencing policymakers and voters to support vouchers, charter schools, cyber schools, and district transfers.

Michigan became one of the first states to allow charter schools in 1994, only a year after Minnesota passed the first charter school law. In 1996, the state created a district transfer program in which students could transfer between districts without interference from their zoned school. In 2011, a DeVos-backed bill removed a cap on the number of charter schools, allowing for rapid growth in the charter sector. The state has also jumped at the opportunity to roll out cyber schools, with mostly for-profit companies taking on students.

The goal of these reforms, whether stated publicly or not, is to increase competition in the education sector so that school systems operate more like a market. The best schools win the most students as well as the funding that goes with them, and the worst schools are not able to support their operation and gradually close down. This dance of supply and demand is supposed to dramatically improve the quality of education.

Whether you agree with this theory or not, the reality is that many states have rolled out market-based reforms in the past few decades. For example, Illinois, a state that was largely protected from choice programs, just launched a new scholarship program earlier this year that will provide public money for private school tuition.

In the private sector, we use a competitive market analysis to understand what risks a company faces from other players in the market. It educates leaders about their competition, and helps marketers craft a focused message for consumers who might choose another firm. In this report, we give a detailed market analysis of choice programs in Michigan to inform leaders across the country how they might market themselves against their competition.

Michigan is an ideal state to conduct this type of analysis. The state’s well-established school choice programs allow us to see the effects of choice policies over several decades. Michigan has a wide variety of districts, from major cities to small rural communities.

To conduct this research, we first looked to the Michigan Department of Education. They collect detailed records of how each school district is gaining and losing students to choice programs. We combined this data with demographic information from the U.S. Census, as well as school funding data from the Michigan Department of Education. We then ran a regression analysis on these data points to determine what characteristics, if any, stand out for districts that lost or gained students from these programs.

While this research is immediately relevant to school leaders in Michigan, the basic mechanics hold true across state lines. School choice is a reality across the country, and knowing the programs that put each district at risk can help school leaders build a marketing strategy that highlights their schools’ strengths against the competition.

Click a section to jump to it!

- Schools of Choice

- Public School Academies: Charter Schools

- Cyber Charters

- The Big Picture

- Craft Your Story

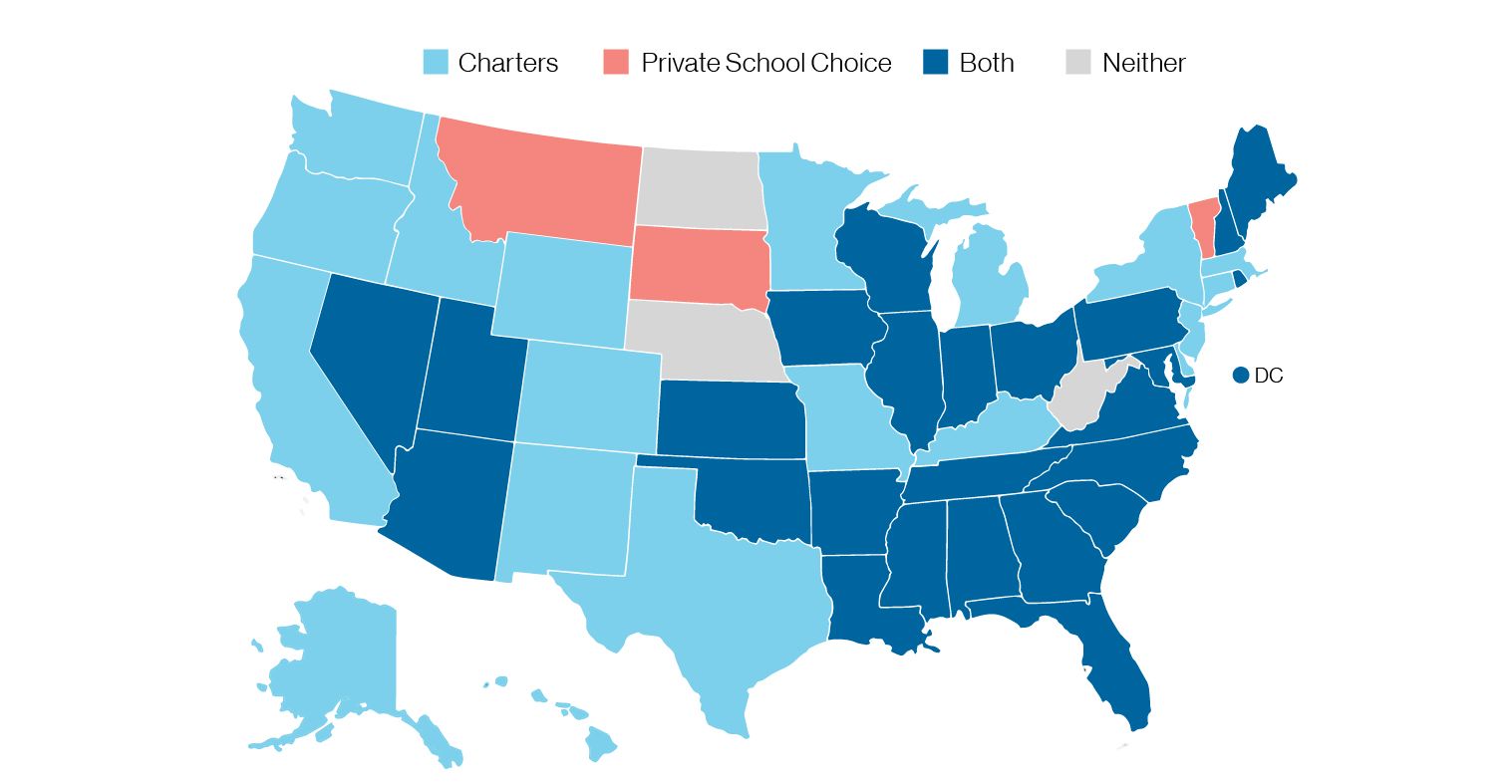

School Choice Laws 2018

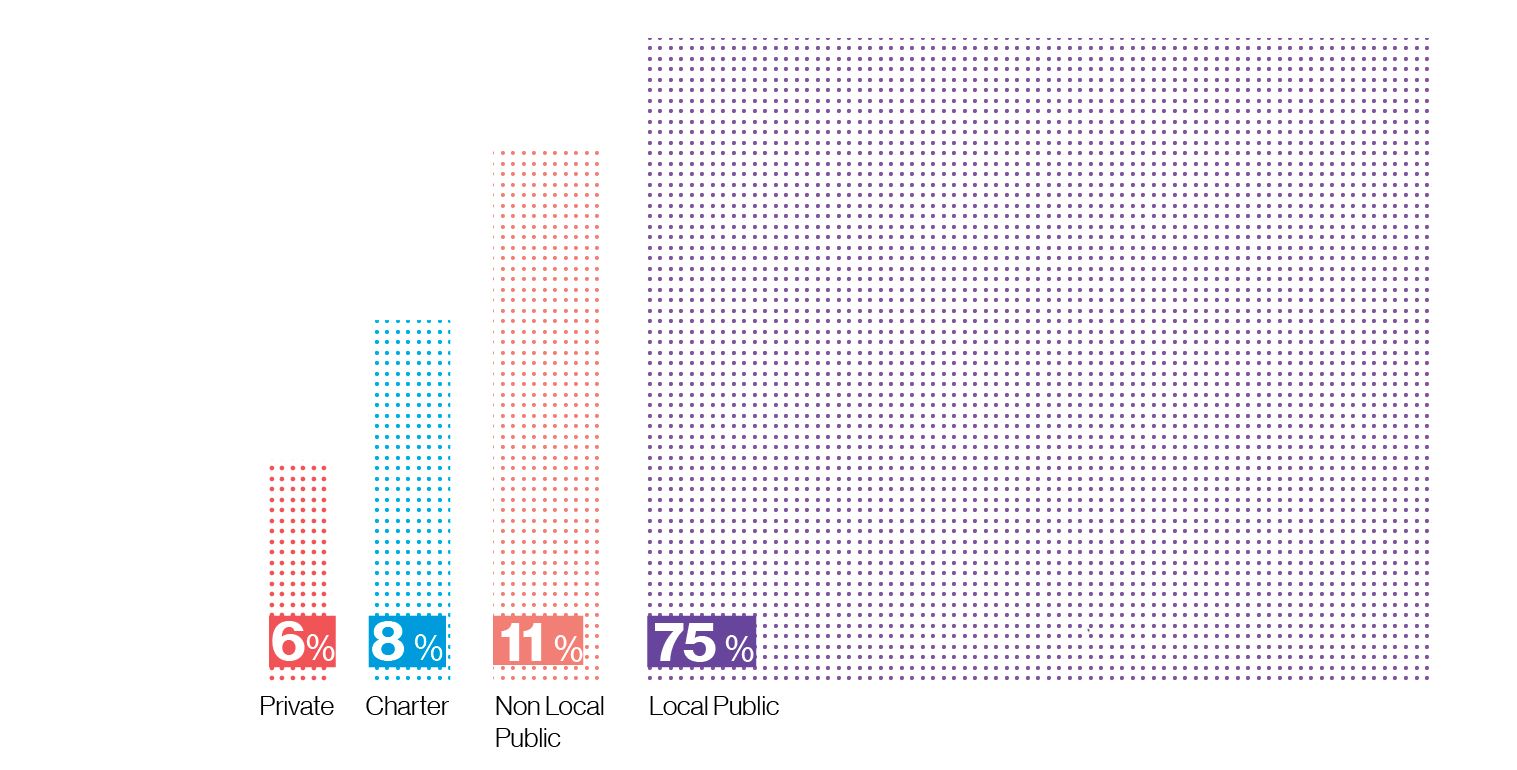

Student Enrollment by School Type

Schools of Choice: Public School Transfers

What it is: A school transfer program that allows student to transfer either to other schools in the district or between neighboring districts.

How it works: Each district has the option to accept transfer students from other districts. This includes both interdistrict transfers within an Intermediate School District or intradistrict transfers from one ISD to another contiguous ISD.

Number of Students: Roughly 11% of students attended school in a non-resident district during the 2016 17 school year.

Who can use it: Any student may transfer to a district that has announced it will take transfer students, subject to capacity. Under this program, a student’s resident district does not have to approve the transfer.

Scope: Statewide

Origin: Section 105 and Section 105c of the State, amendments to the School Aid Act of 1979, allowed the first transfers in 1996.

Schools of Choice is the most commonly used choice program in Michigan — even above the state’s charter program. Around 11% of students utilized the Schools of Choice framework during the 2016-17 school year. The program allows students to transfer to other public schools either in their district or outside of their district, what is referred to as either intradistrict or interdistrict transfers. In Michigan’s system, districts can decide whether or not they would like to accept students, but families do not need to alert their zoned district if they choose to enroll in another public school.

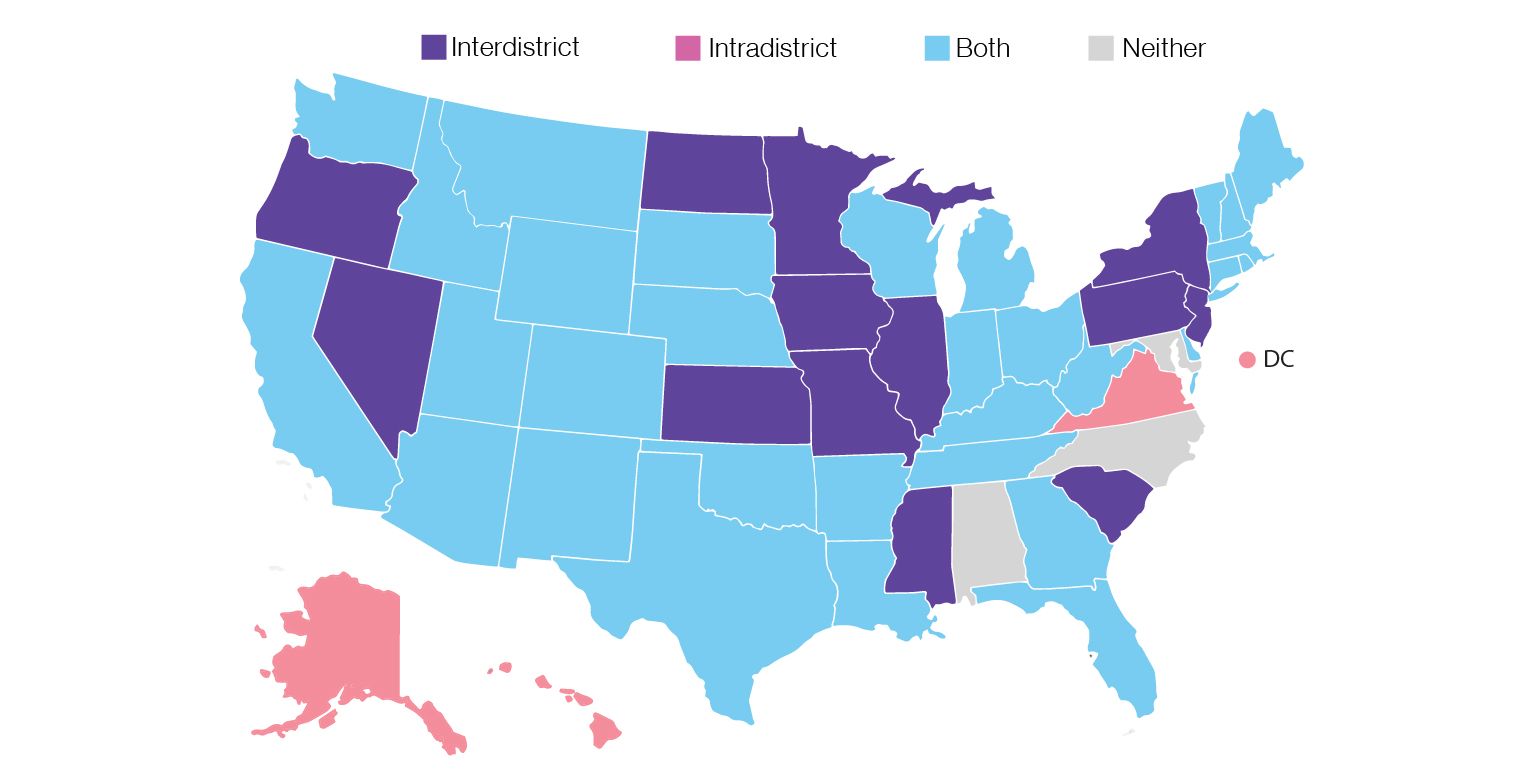

School Transfer Laws by State in 2018

Michigan isn’t alone in providing parents with the option to transfer schools. While students stay within the traditional public school system with Schools of Choice, the intention of the program is to increase parental choice as well as to introduce more competition in schools. The option to transfer schools, whether interdistrict or intradistrict, is available in almost every state.

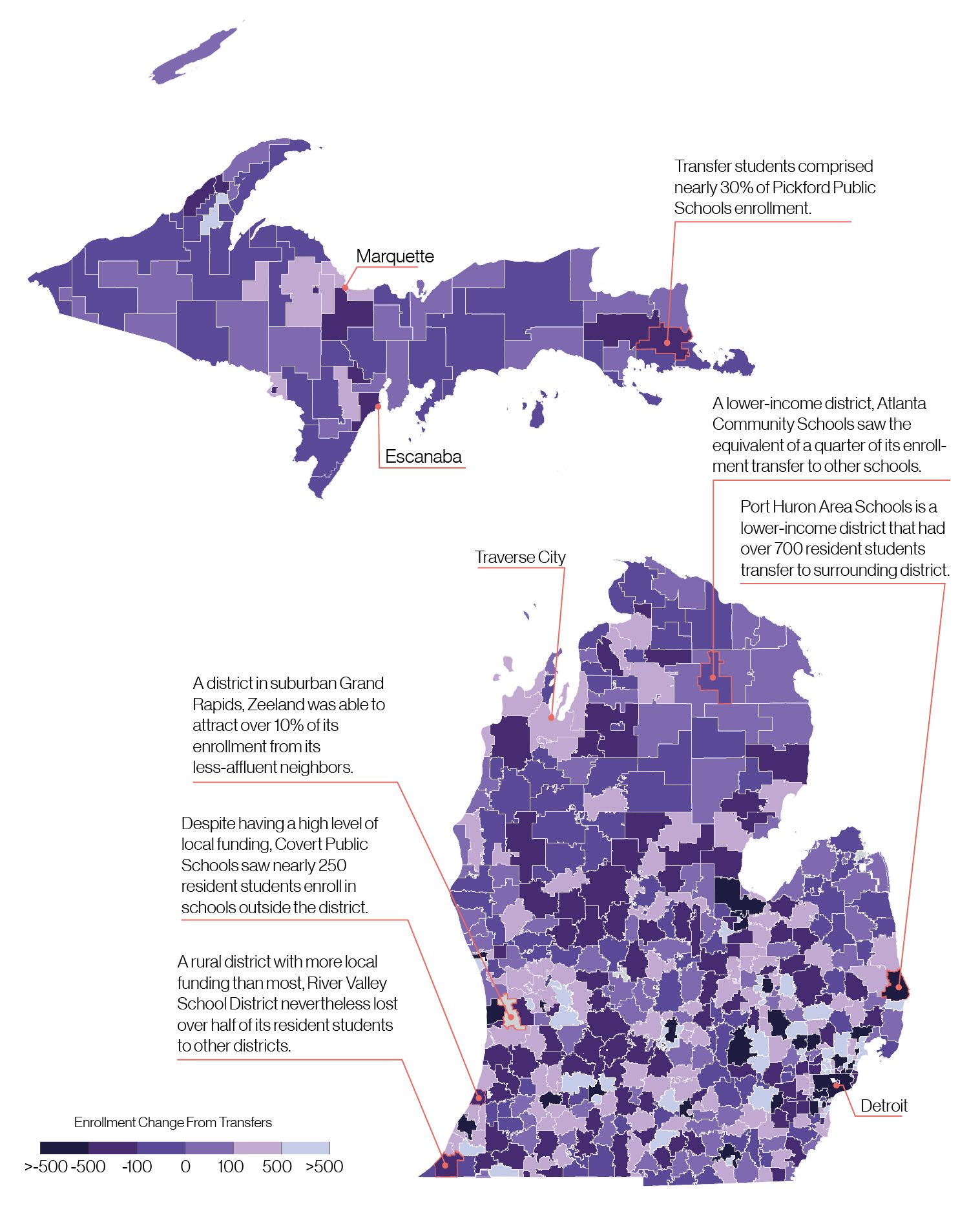

Schools of Choice is used by families across the state, but the effects of the program vary based on the location of each district. While urban districts are seeing the most dramatic losses in students, with large urban districts like Detroit losing thousands of students to school transfers, rural districts are losing a higher proportion of students across the state. Nearly 19% of students in rural areas took advantage of the Schools of Choice program in the 2016- 2017 school year. Urban districts lost a lower percentage of students to the program with only 15.6% of students taking advantage of school transfers. Still, more students in urban areas are using the Schools of Choice program than are enrolling in charters.

Michigan Radio conducted an interview with Dr. Gary Miron, professor of evaluation, measurement, and research at Western Michigan University. Miron has followed Michigan's education system for decades, and mentioned the special strain placed on urban districts:“Suburban Detroit schools are doing better because they can still fill their places through the Schools of Choice program, pulling students out of the urban areas, but our urban schools are suffering.”

In rural and suburban areas across Michigan, high-performing schools are attracting students from neighboring districts. We looked into one district in West Michigan, Zeeland Public Schools, that was gaining hundreds of students from school transfers. Data from Michigan’s Center for Educational Performance and Information put Zeeland in Michigan’s top 15% of districts in terms of attracting Schools of Choice students.

A graduate of the district said that some students—“and they weren’t rare” — drove for over an hour to get to school. Zeeland is larger than most of the rural districts that surround it. That means great sports teams, a gamut of AP classes, and excellent after-school activities like dance and theatre. As the former student mentioned, “Zeeland had the dollars.”

Upper Peninsula or Lower Peninsula, rural or urban, the impact of the Schools of Choice framework is felt around the state.

We found two factors that were statistically significant when it came to district transfers: poverty and high local funding. As poverty increased in a district, more students transferred out. As local funding increased in a district, more students left as well. Generally, we don’t see students transferring into high-poverty areas. But with high levels of local funding, usually associated with wealth in the district, it seems counterintuitive for students to be transferring out. However, higher income families are more able to take advantage of school transfers. They have more time to research programs as well as to transport their students to neighboring districts. These families have more flexibility, allowing them to take advantage of school transfers.

The Takeaway: Schools that serve the highest or lowest income populations can expect families to consider surrounding districts. A student’s zoned school, however, has an advantage over any neighboring districts — the student is ingrained in their community. Marketing the connection between the community and their schools can highlight a zoned school's unique value as compared to neighboring districts.

Net Change in Enrollment from Transfers, 2016-2017

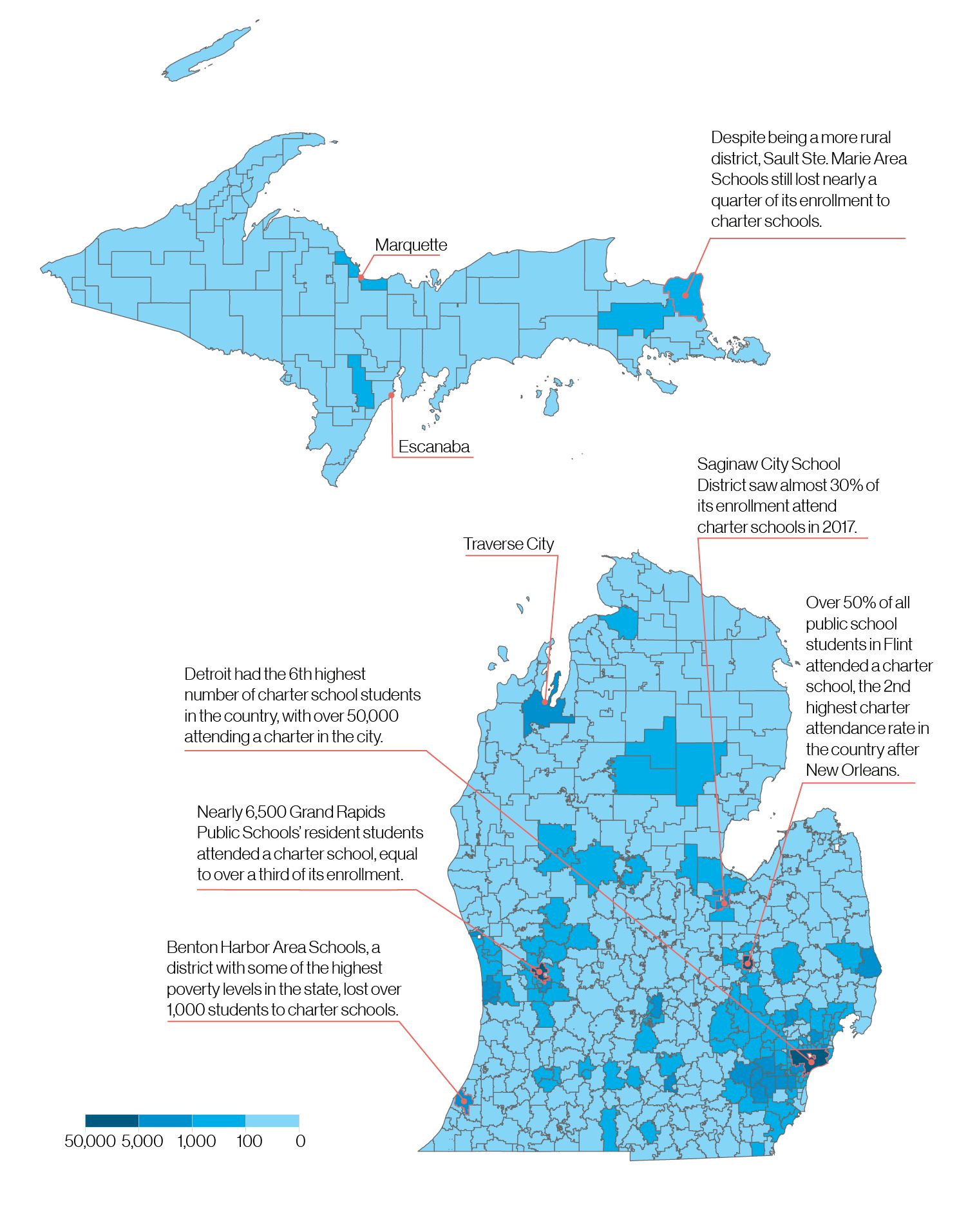

Loss in Enrollment from Charters, 2016-2017

Public School Academies: Charter Schools

What they are: Michigan’s classification for charter schools that can operate under the authority of authorizing bodies, such as a state university, a local education agency, or an intermediate school district.

How they work: A student has to apply to a charter school, but cannot be denied entry on any basis other than capacity. There are three subcategories of charter schools in Michigan:

1. Schools of Excellence - This category applies to either replications of a high-performing charter school, a cyber school, or the conversion of a regular charter based on a strong academic record. These schools may not be located in districts with a graduation rate of 75% or higher during the previous three years.

2. Urban High School Academies - These schools can only be authorized by public state universities, with the goal of increasing high school graduation rates. There are currently 3 Urban High School Academies, all in Detroit.

3. Strict Discipline Academies -These types of charter schools serve suspended, expelled, or incarcerated young people. Michigan currently has seven Strict Discipline Academies across the state.

Number of students: An estimated 146,100 students attended a charter school in 2016-17, according to the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools.

Who can use them: Under Michigan law, charter schools are open to any student.

Scope: Statewide, although charter schools are much more common in urban areas

Origin: Part 6A of the Revised School Code was passed in 1993, authorizing the first Public School Academies in 1994.

Michigan has one of the highest charter concentrations in the country. According to a National Alliance for Public Charter Schools report, over half of Flint and Detroit’s students are enrolled in charters, placing the two cities behind New Orleans in terms of highest charter enrollment in the country.

In total, Michigan enrolls a little more than 8% of their students in charter schools. Once authorized in the mid-90s, the number of charter schools in Michigan skyrocketed, increasing to more than 300 charter schools in just two decades.

Unlike district transfers, charter programs are largely concentrated in Michigan’s larger cities. According to data from the 2016-2017 school year, urban areas enrolled 10% of their students in charters while rural districts only enrolled around 4% of students.

There are a lot of questions about whether or not charter schools improve student outcomes. Studies in cities where the majority of students are enrolled in charter schools, like Detroit, are inconsistent when reporting on the benefits in student achievement. Traditional schools have not done a good job of drawing attention to the negative aspects of transferring to a charter school. Along with the innovation that charters promise comes a risk of failure, especially with newer programs.

Our analysis showed that, as poverty and federal funding increase, the number of students lost to charters follows suit. Because federal funding is largely distributed based on poverty levels, these two factors go hand in hand. Urban districts are more likely to lose students to charters than rural districts because of their concentration in cities.

The Takeaway: Schools in low-income and urban areas are more at risk of losing students to Public School Academies. Charter schools are often seen as more innovative, so publicizing the innovation in your own schools can help show people the great options in their local district. While we don’t recommend focusing solely on other programs’ negative qualities in marketing, knowing the potential risks and benefits of the charters in your district can be helpful when planning your messaging.

Michigan Charter Schools, 1995-2017

School Choice Usage in Michigan, Urban vs. Rural

Cyber Charters

What they are: Full-time online charter schools that may or may not enroll students statewide.

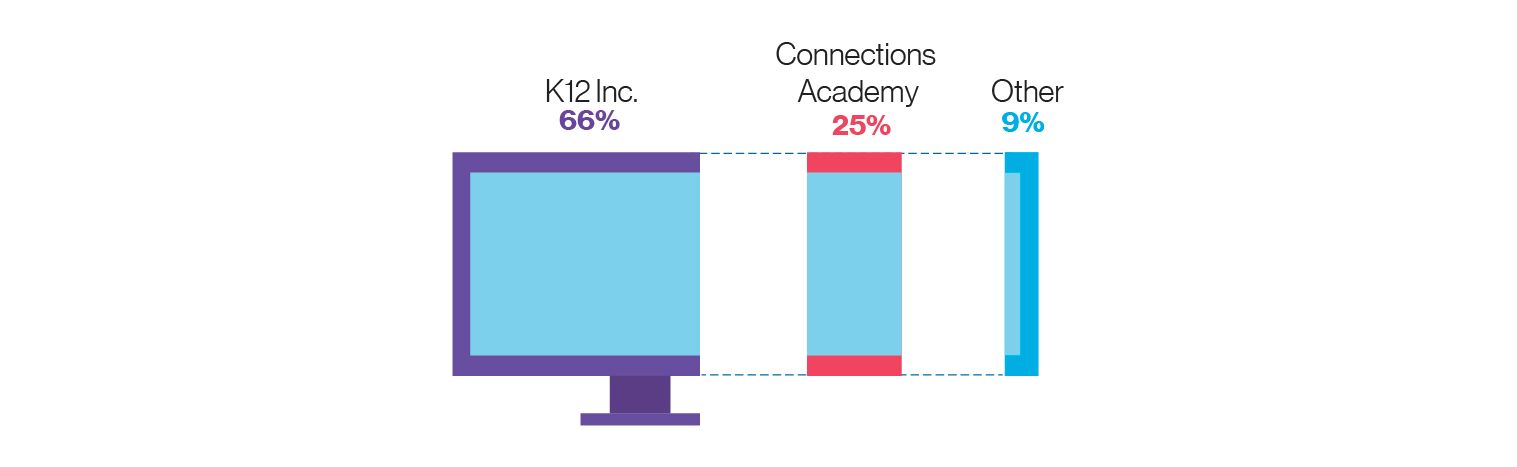

How they work: There are both nonprofit and for-profit cyber schools in Michigan, with the for-profit schools operated by national education management organizations, or EMOs, like K12 Inc. and Connections Academy. Statewide cyber schools can only be authorized in Michigan by state public universities or Bay Mills Community College.

Number of students: Around 9,500 students attended a cyber school in the fall of 2017. There is a cap in place both in terms of statewide enrollment (2% of Michigan’s statewide K-12 enrollment) and in individual schools' enrollment (2,500 in the school’s first year, 5,000 the second, 10,000 the third).

Who can use them: The enrollment process in a cyber school is generally the same as other charter schools in Michigan.

Scope: Statewide

Origin: Cyber schools in Michigan were established in 2009 under Part 6E of the Revised School Code.

Cyber schools are some of the fastest growing programs in the school choice movement, enrolling nearly 300,000 students nationwide. Michigan Virtual Charter Academy and Michigan Great Lakes Virtual Academy have the highest enrollment numbers of any charter school in Michigan.

Both schools are powered by K12 Inc., the biggest player in for-profit cyber education management. Secretary DeVos was an early investor in the company, which provides a state-funded online school option for students from kindergarten through high school.

The appeal of full-time virtual schools is understandable. The option to work from home provides students with chronic illness or disability greater flexibility in their education, which might not be an option in a traditional school building. Many of the programs were originally designed to provide curriculum support to homeschool families, who could join an online program with no additional cost for materials. As the companies have grown, they’ve expanded their audience to target a wide variety of students enrolled in traditional public schools, from Olympic athletes to students seeking asylum from bullying in class.

While online schools are certainly meeting a need for flexible education, full-time virtual schools have a negative reputation in the press. The New York Times, Edweek, MLive, The Washington Post, and USA Today have all shed light on issues with for-profit cyber schools, citing companies using the cyber school model to siphon money from the state, research on schools’ effectiveness, and several companies’ outrageous advertising tactics. One 2015 study from Stanford’s Center for Research on Education Outcomes reported that students in cyber schools lost about 180 days in math over the course of a year — it was as if students hadn’t attended school at all.

If these schools are getting so much bad press, how are they continuing to expand? There’s a growing consensus that the companies’ heavy sales and advertising campaigns are attracting students. K12 Inc. and Connections Academy both advertise on television, radio, website banners, and social media. A study from USA Today revealed that K12 Inc. has historically targeted children by buying ads on television networks like Cartoon Network or Nickelodeon.

As a means to compete, districts are opening their own cyber schools. The National Education Policy Center reported that the schools “have typically been small, with limited enrollment.” However, there’s no question that districts around the country are adapting to meet the needs of students enrolling in cyber charters.

The Takeaway: Districts that serve high poverty areas are more likely to lose students to cyber charters. Online schools are marketing their flexibility and free programming, but they lack proof of academic performance. Traditional public schools can market their extracurriculars, students’ academic achievements, student-teacher relationships, and school traditions as a means to highlight their strengths in comparison with cyber schools’ weaknesses.

2017 Michigan Cyber Charter Enrollment by Education Management Organization

Growth in Michigan Virtual Schools Over Time

The Big Picture

At the end of the day, the numbers that really matter are how many students a district gains or loses in total. A family who chooses to enroll their kindergartener in cyber schools for the entirety of their elementary education means the loss of tens of thousands of dollars in funding for the district.

During the 2016-2017 school year in Michigan, the average number of students lost per district was around 269 students, skewed by some of the larger districts’ losses. The median Michigan district lost 23 students to school choice. In many cases, such heavy drops in enrollment meant the loss of hundreds of thousands of dollars in state funding.

When comparing the total change in enrollment with a variety of demographic and funding statistics, our analysis returned two seemingly conflicting results. Districts with a high concentration of poverty as well as districts with high levels of local funding are more likely to lose students to choice programs.

Concentrated Poverty

It’s not surprising that concentrated poverty correlates with students leaving a district. Research on academic performance shows a direct connection between poverty and low school performance. At the risk of simplifying a complicated issue, children in poverty often need more resources from the school, which can put a strain on the district’s budget. As a result, parents in these areas make heavy use of choice programs.

We spoke to a teacher from a suburb of Flint about her experience with Michigan’s choice programs. She noted the same idea, “We did see an exodus of the ‘better families’ in our district.” If public schools are perceived as low-performing, and parents have another option, they’ll take it. Whether this is the best move for the child — or for the neighborhood’s schools — is a harder question to answer.

High Local Funding

On the other end of the spectrum, districts with more local funding are also losing students to choice programs. Local funding can be a measure of the area’s wealth as it is most often derived from local property values. At first, this idea seems counterintuitive. Why would students leave schools with higher funding? While schools in the area might not have as significant of academic problems or budgetary strain as schools with high poverty levels, they face a different competition concern: parents who are willing and able to utilize school choice programs to their fullest extent.

Upper middle class parents have more flexibility to pull their child out of public schools if they think there is a better option for their education. They have the resources to travel to a school miles away, to enroll in a private school, or to stay at home to monitor their student’s cyber education. If your community has more high-income families, it’s more likely that you could lose students to choice programs.

Craft Your Story

The reality is that, once competition is introduced into a market, it is hard to remove. If school choice programs haven’t spread through your state, it’s likely that those days are coming sooner rather than later.

Schools who want to succeed in a world of school choice need to find ways to respond to the specific concerns of their local community. This means understanding why families are leaving their zoned schools and what they are seeking in other options.

The first step in any marketing effort is clearly articulating your unique value proposition. How can your schools meet students’ needs in a way that others cannot? Forming a clear and focused message about your district’s unique value, then continually spreading that message across communication channels, can shift perceptions of your district, ultimately helping your schools thrive in a competitive K-12 market.

SchoolCEO is free for K-12 school leaders. Subscribe below to stay connected with us!