Dr. Steve Webb: Building Community Trust

How Vancouver Public Schools earned long-term community confidence—and leveraged it to win big with their bond

“There is a reason I do this work,” Dr. Steve Webb of Vancouver Public Schools tells us. “I know something first hand about generational poverty.” Neither of Webb’s parents graduated from high school, and neither set of his grandparents did either. As he speaks of his students’ challenges, you can hear the passion in his voice. “Poverty is not a learning disability,” he says, “but it presents real barriers to student success in too many classrooms in our country.”

Webb is currently serving his 12th year as superintendent of VPS, which sits on the north bank of the Columbia River, just across the water from Oregon. This large Washington district, serving about 23,400 students, has experienced rapid growth and diversification over the last decade as a result of nearby Portland’s rising costs of living. Families are relocating to Vancouver for more affordable housing, which has caused a shift in the district’s demographics; around 43% of students now qualify for free and reduced meals, and roughly 14% need English learning services across the district.

Fortunately, they have a school leader whose mission is as personal as it is professional. “If we’re serious about getting more kids across the finish line—Black and Brown, differently abled, second language learners—rather than focus on the symptoms, we need to get to the root cause,” Webb says. “And decades of research demonstrates the correlational relationship between poverty and student learning.”

Needless to say, Webb’s 35-year career in education has centered on students who need more wraparound support from their schools. His leadership specializes in the juncture between education, communications, and community building—earning him not only 2016 Washington State Superintendent of the Year, but also one of four finalist spots for AASA’s national title. He’s been featured as one of EdWeek’s Leaders to Learn From and received NSPRA’s 2018 Bob Grossman Leadership in School Communications Award.

When Webb took the helm in 2008, he partnered with Chief of Staff and Chief Communications Officer Tom Hagley, who’s now in his 28th year at VPS. Together, they renewed the district’s focus on community support for students. But instead of just implementing new programs, Webb gave the community the impetus to design their new schools. “What you help co-create, you own and support. That, in and of itself, is a standard practice here in the system and in the community,” he says.

Webb invested heavily in communications: not just sending stories out, but asking the community for feedback. Over time, this two-way communications work built the connection between the community and their schools. So as the need for a bond surfaced around 2015, the VPS team knew they’d need to build on the momentum of their community connections and story-driven communications. Since many schools needed to be completely replaced, the district’s bond would also come with a hefty price tag. Fast-forward to 2017, and the district would pass their $458 million referendum with overwhelming support. The long-term trust and personal connections the district had built within the community had more than paid off.

It’s clear that strengthening community trust and buy-in is an everyday focus for VPS. “Sometimes you have to go slow to go fast,” Webb advises. “It isn’t about getting out, identifying a set of projects, and then just launching a campaign. If you try to microwave the process, you’ll likely not get the kind of result that you had hoped for.” Instead, VPS stays focused on gaining supporters along the way. “That will net the kind of results that you need at the ballot box,” Webb says.

The Community Approach

Long before their 2017 bond, Webb and his team committed to operating and maintaining community schools. The fact that these programs would garner more support for the district was a bonus, but not the focus of their efforts. The focus, as always, was the students—especially those with the greatest needs. For Webb, education is a pathway out of poverty. “It’s not a hand-out; it’s a hand-up,” he says. “It’s about reducing the barriers that present challenges for kids to learn in school. If a child is hungry, if they don’t know where they’ll sleep tonight—it’s going to impact their ability to learn.”

According to the Coalition for Community Schools, these facilities provide expanded learning opportunities outside of the classroom, offer essential health and social services, and engage families and communities as assets in the lives of their children and youth.

As of 2018, VPS was spending about $1.7 million of their own resources annually on the community schools initiative, with community partners providing another $3.8 million in funds and in-kind support, according to Phi Delta Kappan.

One reason for the initiative’s success, however, was that Webb wasn’t spearheading the movement alone. “In the 2007-2008 school year, the district engaged in a strategic planning process that involved hundreds of internal and external stakeholders,” Webb tells us. “That series of conversations resulted in identifying strategic goal areas. One of those goal areas focused on family and community engagement and about how we can leverage partnerships and relationships in such a way that improves student achievement.”

As part of their move toward community schools, Webb, Hagley, and their team began to open more Family-Community Resource Centers (FCRCs) across the district. These on-campus facilities “remove barriers and connect families with available community resources” to increase student success. FCRCs conduct a needs assessment of the families in their neighborhoods and serve as local centers to “build collective capacity within the neighborhood to bring those resource supports to bear.”

Several years ago, when one of the district’s most impoverished neighborhoods faced a crisis, FCRCs came to the rescue. “Just a few weeks before Christmas, there was a landlord who issued letters to vacate an apartment complex,” Hagley explains. The apartments were home to several of the district’s families, so the local FCRC stepped in to help. “Our partners were able to wrap support around those families who were impacted,” he adds. Not only did the FCRC provide food and shelter, they also paired families with legal services and housing experts. Within two weeks, the Washington neighborhood FCRC raised nearly $100,000 for families in need. “These families could’ve been put out on the streets at Christmas,” Hagley says. “But they had a place to go.”

And the impact didn’t stop there. It also opened up a broader conversation in the community around local housing policies that eventually resulted in a new city ordinance giving residents more time to vacate their homes in the event of an eviction. The conversation also led voters to approving a housing levy to build affordable apartment complexes in the area. “It speaks to the transformational power that schools can have in communities,” Webb says.

In 2008, VPS was just opening their second FCRC. Now, they operate 18 centers and aim to provide resource services in all of their schools by the end of 2020. They even have two mobile units that serve students in the north end of the district. And they’ve also established partnerships with more than 750 outside entities—from local businesses to faith communities—to ensure these FCRCs can continue to meet community and student needs.

The district also funds full-time FCRC coordinator positions in all 18 of their centers. “That person’s job is dedicated to mobilizing partnerships—that’s their full-time work,” Hagley explains. “It sends a message to the broader community that the district’s doors are wide open.” Hagley says that having coordinators has also “provided a conduit for collaboration at the school level that goes beyond the principal.”

The VPS team believes that by investing in the lives of their students and families, they’ve won the trust of their community. The data seems to back this up. “In the voting precinct results over time, we’ve seen dramatic changes as schools have been rebuilt with these Family-Community Resource Center connections and partnerships,” Hagley tells us. “The areas of town that were previously poverty-affected and had low levels of connections with their schools—those precinct results have increased dramatically when it comes to people supporting levies and bond measures.”

Building on Momentum

By 2015, several schools in the district desperately needed repairs or replacement. Fortunately, the trust VPS had established with their stakeholders gave them the confidence to start planning a bond campaign. But in order to earn and maintain the kind of buy-in needed for success, the district knew they’d have to keep communicating their vision.

“People tend to focus more on getting the information out and trying to persuade voters to pass a measure,” Hagley says. “But, oftentimes, voters can’t see exactly what they would be benefiting from. They don’t have a clear vision of what the district wants to accomplish.”

VPS, however, had laid most of the groundwork before the official bond campaign ever began. They’d made it hard not to see their vision for community schools that care for the whole child. “Without question, I am absolutely confident that a decade’s worth of work translated into additional support for this bond program request,” Webb tells us.

To determine what shape a potential bond package should take, VPS stayed focused on their stakeholders. They turned to their community for help in “rethinking, reimagining, and rebuilding schools for the future” by hosting 10 formal community meetings—they call them “symposia”—and 37 onsite meetings at individual schools. Over the last decade, the district has hosted over 50 symposia on various topics related to their schools and community. With these bond symposia, specifically, VPS wanted to make sure they acknowledged every community need and concern.

And they do mean every concern—especially those of underserved demographics. “We have to design focus group conversations in very targeted ways,” Webb explains. “We might not necessarily hear from our Spanish-speaking families unless we invite them to the table. So by deliberately reaching out to historically under-represented audiences or stakeholders, we’re making sure they’ve got a voice.”

VPS’s two mobile FCRCs are proof that this district listens to their community. “Mobile units surfaced in a conversation through one of our symposia,” Hagley tells us. Because VPS doesn’t have the budget or need to hire more FCRC coordinators, these mobile resource centers are able to serve students in the northern part of the district who wouldn’t otherwise have access. “We’re enlisting great minds to co-create solutions,” Webb adds.

Not only did engaging with the community in these ways guide the district’s planning, but it also created “a cadre of really enthusiastic champions for each of those projects,” Hagley says. “There’s always this energy in the room when we get people from different backgrounds together to talk about how we could make this the best possible school district. It creates a buzz in their local community. If they’re a teacher, they go back and talk with their colleagues. Students talk with other kids. It builds momentum toward the bond effort.”

And even after the bond has been passed and a facility built, this initial engagement process gives students and parents a sense of ownership over the finished product. “When you directly engage students and staff members, parents, and others from the community, you create a lasting source of pride for those folks,” Hagley says. “They often come back and point to certain aspects of the school after it’s been built and say, That was my suggestion!”

For Webb, building that sense of community ownership is paramount—not just for bond elections, but for everything the district does. “These aren’t my schools,” he says adamantly. “They’re not the board’s schools. These are community schools, and our community invests in their children like no other in the country.”

Telling Stories

Superintendent Webb sometimes refers to himself as his district’s “storyteller-in-chief”— a moniker he wears proudly. “I’m absolutely committed to a year-round communications program and have invested significantly in our communications teams,” he tells SchoolCEO. “At the end of the day, I can’t do everything from this office, but I can continue to communicate our great work, our strategic priorities, our results. That equips everyone in the organization—from a custodian to a board director—with the same sense of purpose, vision, hope, and aspiration that we want for our children in public schools. People need to feel invested. They need to feel empowered to act. That’s why it’s incumbent upon us to tell those stories.”

Being chief storyteller involves not only communicating Vancouver’s vision, but also spotlighting past and current successes—FCRCs, for example—especially when the district needs community support for efforts like bonds and levies. “All of our communication efforts are imbedded with our strategic work,” Webb explains. “It’s about telling our story related to our strategic work in such a way that helps inform and shape prospective work.”

Like most school systems across the country, VPS also faces legal limits as to how they can market their bond measures. “Any advocacy where we’re encouraging people to vote Yes will have to come from volunteer groups,” Webb tells us.

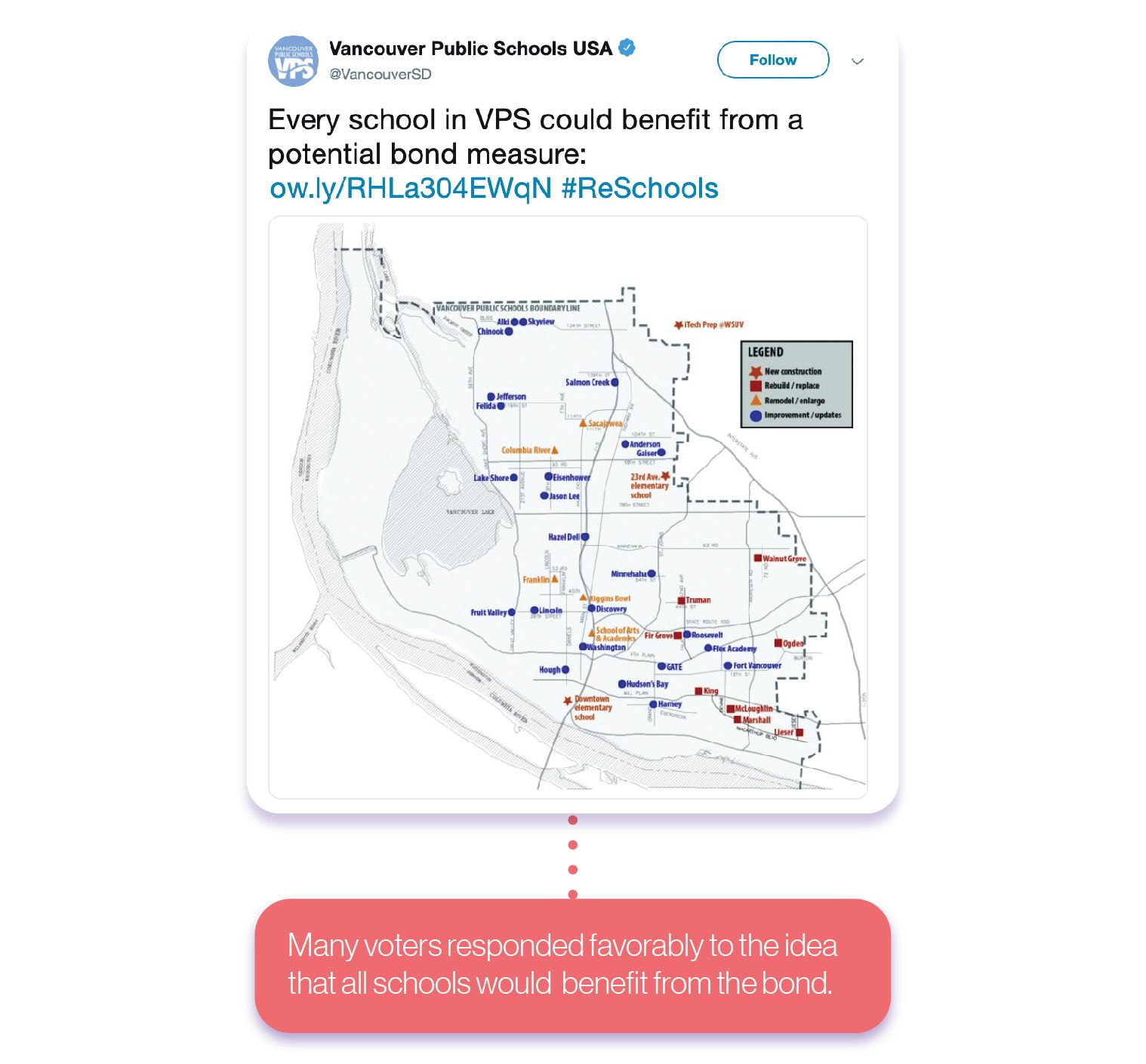

Initial community surveys prior to the bond planning process helped the district get a sense of how to reach their stakeholders. “That enables us to test some messages,” Hagley says. “Then we know what statement of facts would be most compelling to cause people to support the measure before the campaign.” After testing around 10 themes in those first few surveys, VPS found that a few stuck out to the community, like new HVACS and increased safety and security. Voters also responded favorably to the idea of “a chicken in every pot,” adds Webb—“the fact that all schools

would benefit.”

Once they determined which messages resonated most with the public, VPS hammered those themes home.

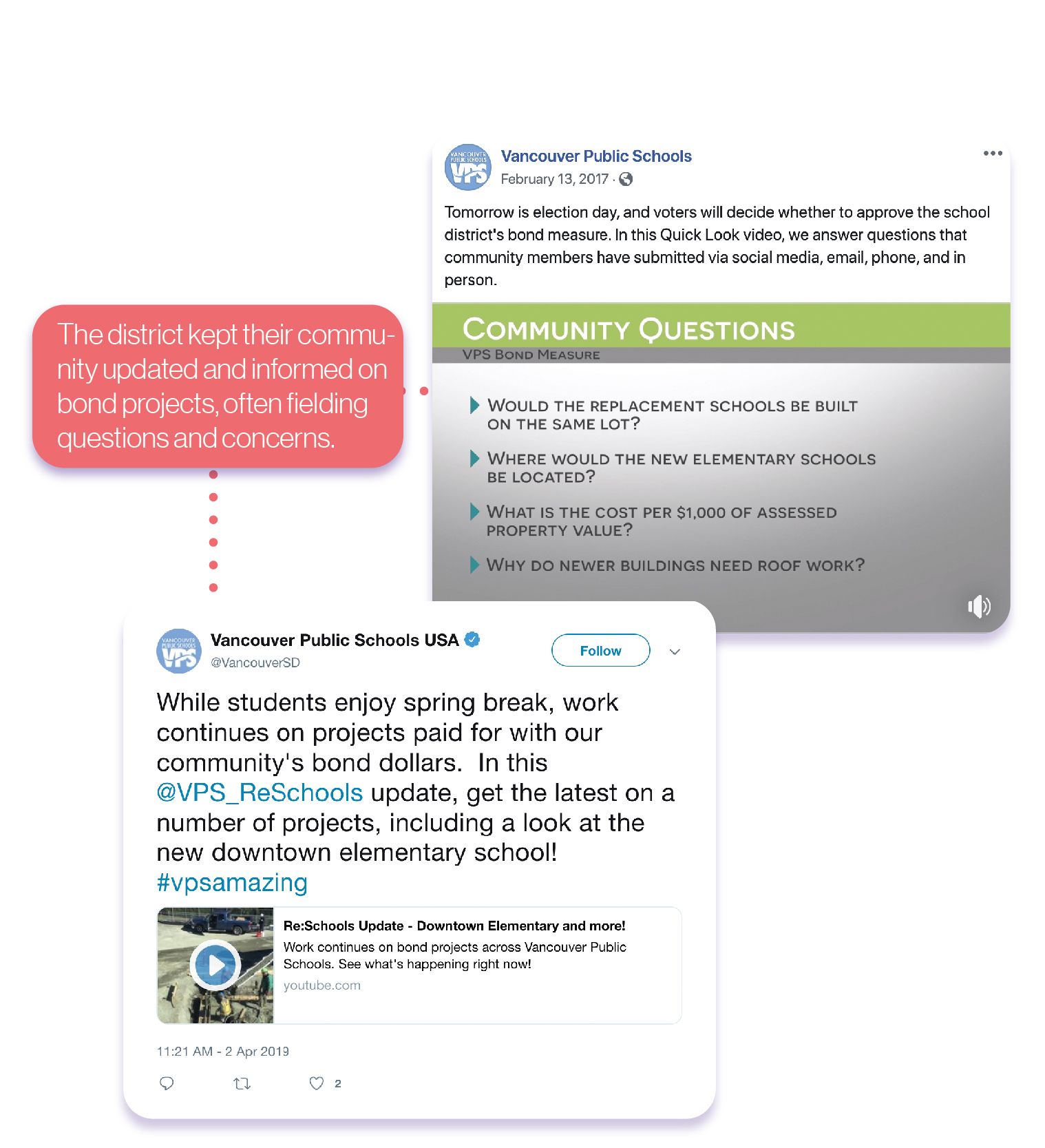

“We just repeated those over and over and over again in different ways,” says Hagley. He cites the Rule of Seven—the idea that people have to hear marketing messages at least seven times before they’ll take any action. “We’re mindful that we need to repeat the information at least six or seven different times in different ways in order to break through all of the other information that people receive every day in their regular lives.”

To deliver their message to as many stakeholders as possible, VPS implemented a whole laundry list of approaches: “pretty much everything, except for skywriting,” Hagley tells us. “We did 90 presentations to staff and community groups. We also did open houses in each neighborhood that was going to benefit from a project school, and we used our website and social media to drive people to the site.” Outside of these tools and a mobile app, the district also used more traditional methods to reach voters.

“We used outdoor signage—sidewalk signs and banners—to draw attention to passersby that this was a site of a future bond project,” Hagley adds.

Listening to the Kids

Just as they do everyday, VPS kept students at the center of planning and marketing for their bond. “We always start with student learning and the kind of outcomes we want to achieve,” says Webb. “How do we backwards-map from those outcomes in order to achieve the kind of learning environments kids need?”

And here’s something crucial—the district doesn’t presume to know what those needs are. They ask the kids themselves. “Frankly, sometimes students have a different perspective than the adults in the room,” Webb says. “Inviting those voices to the table makes sure we don’t construct schools that don’t make sense to the kids we serve. I think it’s critically important that we empower students to tell us what they need and what their aspirations are.” Of course, that means getting input from a diverse group of students. “We want to make sure we listen to our second language learners and to the different populations that make up an entire student body,” he says.

The same emphasis on student needs and success districtwide that drove the bond package itself also anchored the district’s marketing. Telling the VPS story means consistently maintaining that focus on their greatest asset: the kids. “Visually, in all of our communications, we would always have students front and center, focusing on what’s good for them,” Webb says. “And not only students today, but generations of students. These schools are an investment the community makes to build assets that will last for 50 years or more.”

For Webb—and for VPS—it all goes back to working together to give every student their best shot at a promising, successful future. “It does take a village,” he adds, “of schools, families, and community partners interacting to strengthen opportunities for kids to learn and grow.”

SchoolCEO is free for K-12 school leaders. Subscribe below to stay connected with us!