The Cultural Lens: Snapshots From Districts Doing the Work

Snapshots of school leaders creating strong cultures in their districts through careful, deliberate effort.

From private sector companies to public school classrooms, culture has become the topic on everyone’s hearts and minds. Of course, that’s because it can make or break any organization or community. Think of culture as your district’s roots—the beliefs, values, and assumptions tying everyone in your school family together. Planting and nurturing a strong culture allows students, faculty, and staff to flourish as individuals and as a community.

Here are four leaders who have instituted positive, empowering cultures in their districts—unifying students, staff, and community members around one central goal.

Dr. Yolanda Cargile was fighting for kids long before she became a school leader. Prior to her career in education, she was a practicing social worker, serving teen mothers and investigating childhood abuse and neglect. “My background is unique, but I think it makes me a better educator,” Cargile tells us. “Those experiences provided me with a framework for connecting with families to bridge the gaps between school and home.”

Since February 2020, Cargile has been superintendent of Center School District in her home state of Missouri, where she’s helping create a culture of inclusion and equity for every student and staff member. “We know that across the nation, there’s an academic achievement gap where our white students are outperforming our Black and Brown students,” she says. “That’s an issue.”

“For so many years, race has been a topic that’s not even discussed for fear of offending or sounding ignorant,” Cargile tells us. “I like to create spaces where we can have those conversations, provide opportunities to discuss biases, and gain a better understanding of white privilege. Equitable education only happens when your teachers have the tools that they need to better serve children. Luckily for me, I’ve joined a district and community that sees the importance of this work.”

Cargile begins every district meeting with a quote focused on racial equity; staff then discuss how it resonates with them on professional and personal levels. “For my predominantly white team, that creates this level of comfort for them to be able to talk about race,” she explains.

But Cargile isn’t just starting conversations about race; she’s working to create an actively anti-racist community, both in and out of schools. Last May, when the killing of George Floyd intensified the national conversation on police brutality toward the Black community, Cargile and the district knew they couldn’t stay quiet. “We released a statement to our community with a stance that promotes anti-racist beliefs and actions,” she tells us.

The district is also leading a community book study in partnership with the Center Education Foundation—a local nonprofit that awards grants to Center teachers. The Center community is currently reading Unconscious Bias in Schools: A Developmental Approach to Exploring Race and Racism by Tracey A. Benson and Sarah E. Fiarman. “It’s written by a white woman and a Black man,” Cargile explains, “and their dialogue in this book is absolutely fabulous. They are able to have genuine and real conversations around their own biases and beliefs about race and how they show up for children. So reading this book allows us to see what the actual dialogue can look like in a healthy way.”

For Cargile, good leadership is about creating these kinds of environments, “where people can engage one another and learn from experiences,” she says. But it’s also about making sure every voice is heard. “When we’re making big decisions in the district, I always ask my team, Who else needs to be at this table?” she tells us. “The white people in the district shouldn’t be making all the decisions when we serve predominantly Black and Brown children.” In fact, Cargile has promoted the need for diverse voices on every committee and project the district has started since her tenure began. “When we roll out new initiatives or release big documents like our strategic plan, we’re really forcing our team to ask, Is it diverse?” she adds. She also got the school board behind CSD’s mission of anti-racism; they currently begin all board meetings with quotes on racial equity as well.

While Cargile acknowledges the collective effort necessary to create and nurture an inclusive culture, she understands the importance of showing up, too. “I’m a firm believer in the idea that what you permit, you promote; what you measure, you get more of,” she says.

To build crucial relationships with students, Cargile leads a group of middle and high school girls called Sisters Inspiring Sisters (SIS). Once a month, the group meets with Cargile and a guest speaker to talk about topics like education, community, self-esteem, and college and career readiness. Although SIS is specifically designed for girls, the district is working on launching a similar group for male students. “I want to model for my staff that this is how you make connections with children,” she says. “The only way you’re going to know them by their name, needs, and strengths is to create opportunities to build those relationships.”

You could view Sisters Inspiring Sisters as a perfect microcosm of the equity work taking place across Center School District—a diverse group discussing their needs and perspectives to better understand and serve one another. “It’s important that I have a diverse group of young ladies because it allows them to interact with me as a Black female,” Cargile tells us. “To have that positive relationship tears away those misconceptions that the media often presents about Black and Brown women and men. I want to leave a positive image for all students so that I serve as a role model, a person they see in a positive light.”

When he first came to Oregon CUSD 220 fourteen years ago, Dr. Tom Mahoney faced some unique challenges. “I discovered that our entire district was a decade behind in technology infrastructure and instructional technology,” he tells SchoolCEO. “Not only that, but our social studies textbooks still had East and West Germany in them. For 20 years, there had been limited purchasing of new instructional resources.”

Along with facing financial troubles, Mahoney’s new district had seen 23 different district administrators and five superintendents in just 10 years. Prior to that time, OCUSD 220 had undergone a forced consolidation with Mt. Morris, a neighboring school district, which left many feeling unwanted and unheard. Soon after the consolidation, a fire resulted in the destruction of a Mt. Morris elementary building. While no one was injured, the loss of the building forced two staffs to merge into one at the remaining elementary school. “There was a cultural disruption because there was little work done to integrate staff and develop a shared vision,” says Mahoney. “The impact of these incidents resulted in resentment and, at times, strife within our district community.”

With his work cut out for him, Mahoney made it a priority to get everyone on the same page. “We first affirmed our mission statement with the board and community, making sure that our focus was on fulfilling that mission,” he tells us. “We identified four pillars—academics, activities, service, and leadership—and those became our focus as we deconstructed and reconstructed every system in the school district. This work laid the foundation for where we are today.”

Mahoney also worked to bring both halves of the consolidated district together. “I made an intentional effort to serve in both communities, and I spent as much time as I could in Mt. Morris,” he says. “They were concerned they would lose their one remaining school building, but the board and I were able to reassure the Mt. Morris community that we would do everything in our power to keep the building open for as long as possible. It wasn’t any one event that brought us together—it was a combination of students being accepting of the change and the district being intentional in serving both communities.”

While rebuilding OCUSD 220 from the inside out, Mahoney learned early on that vulnerability was a key part of being an effective leader. “At my first superintendent meeting in our region, there were probably about 22 superintendents talking about Common Core and how they were implementing it in their districts,” says Mahoney.

“Every superintendent before me was saying that it was going great,” he tells us. “No one was talking about the problems they were having. So when it was my turn, I just said to them honestly, I think I’m screwed—because I knew that the work in my district was hard and often did not progress in a linear fashion.” This experience showed Mahoney the importance of being vulnerable. By admitting his own struggles, he could learn from others and get the help he needed.

After the meeting, he intentionally started growing his own network to learn from and connect with other superintendents, as well as lean on them for support and guidance. “Every year I build a group of four or five superintendents to get together once a month and just be honest,” says Mahoney. “Every time there’s a new superintendent in our area, we invite that person to join us. It helps me share problems and gain insight, as well as remember what it was like when I first started in the position.”

The experience of being vulnerable with his peers about failure showed Mahoney how important it was to extend this same grace to his teachers, board, and staff. By acknowledging areas where you can grow, he learned, you can reach success quicker. “My message to new teachers every year is to fail faster. We can’t innovate and change unless we embrace failure,” he says. “I have a fantastic board that understands this, too—we celebrate the failures. If we try an initiative and it fails, we look at the results, see what we can learn, and then look to what’s next. We recognize that to succeed, you have to fail quite often.”

While the pandemic has brought unforeseen challenges to OCUSD 220’s staff, Mahoney and his team have built a culture of vulnerability that has stayed strong and helpful. “Remember, most teachers were good students and enjoyed school. They enjoyed primary school, went to college to study school, and left college to work in school. They’re not used to failure,” says Mahoney. “Since January I’ve been encouraging my team to have those hard conversations, sharing with our staff that it’s okay that they’re in a crisis, and we’re going to help them.” Mahoney understands that this change doesn’t happen overnight, but if they’re willing to be vulnerable, teachers can be what he calls comfortably uncomfortable. “By having these tough conversations, we’re getting back to the place where our teachers are facing new challenges, but not so much that the challenges feel unbearable.”

With an environment that fosters this type of vulnerability, OCUSD 220’s faculty and staff are thriving. “It takes courage to have these conversations, and the culture that has been previously built with your team will determine your success in inviting vulnerability,” says Mahoney. “Culture is extremely fragile—it takes one poor decision to break it. You have to cultivate it, be careful with it, and behave in a way that builds it over time.”

“My message to new teachers every year is to fail faster. We can’t innovate and change unless we embrace failure.”

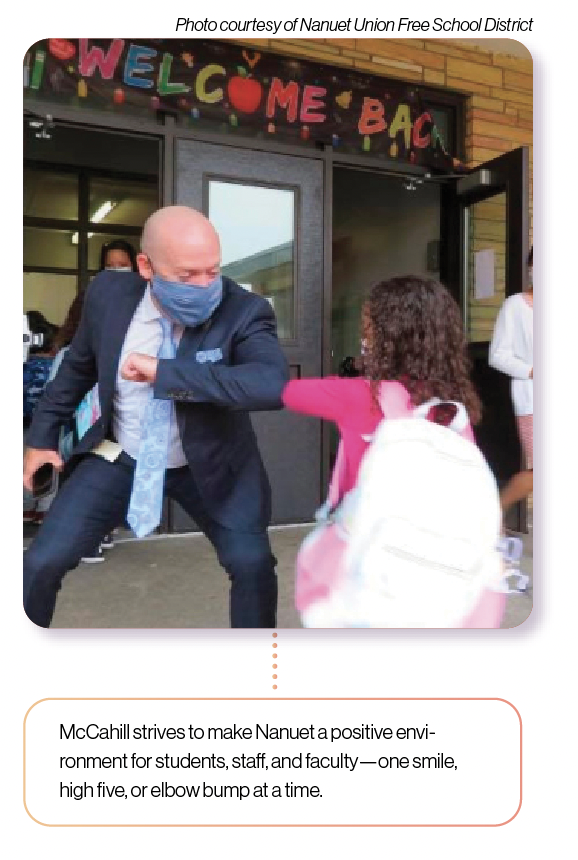

It’s not unusual to see a knight in shining armor walking the halls of Nanuet Union Free School District’s elementary schools. If you see him, don’t be alarmed—you haven’t traveled back in time. It’s just Superintendent Dr. Kevin McCahill, proclaiming his Nanuet pride.

McCahill’s road to Nanuet started on Wall Street, where he began his career as a bond broker. Despite making good money and using his love of math and finance, he was left unsatisfied. “In my time in the corporate world, we were very goal-oriented about metrics and profits—not so much celebrating people’s efforts, acknowledging people, being proud of what we were doing,” he tells SchoolCEO. “I just felt like something was missing.”

As it turns out, the missing piece was right in front of him. McCahill’s sister was a teacher. So was his fiancee, now wife. “They would tell me about their days, and I’d say, This is amazing,” he recalls. “You’re making a living but you’re also providing service.” Before long, the wheels in McCahill’s head started turning. “The education world checked two really big boxes for me,” he says. “I started thinking to myself, Why look any further?”

McCahill began his career as a math teacher, eventually working his way from an assistant principalship at Pearl River School District to a curriculum coach position at nearby Nanuet. From the classroom to the administrative office, he was known for his over-the-top enthusiasm—and he’s brought that positive energy into his superintendency. “Especially since I left something and took a risk to do something new in this field, I think I would be cheating myself if I buttoned up just because I think that’s what I’m supposed to do,” he says. “Now, as a superintendent, I refuse to let up on the positivity and the enthusiasm, on being a cheerleader for the great work that schools do. I have the opportunity to be an ambassador for public schools, to scream at the top of a mountain with a megaphone how amazing schools are. I wear that with pride."

And he does wear his Nanuet pride—literally. “We’re the Nanuet Knights, so I dress up like a knight for the kids,” he says. “I go down to the elementary schools in full Knights gear and give high fives.” The kids, of course, love it. Seeing McCahill clunking around in armor amps them up, getting them just as excited about school as their superintendent is.

We’ve all heard it before: Culture flows from the top. And in Nanuet’s case, McCahill’s enthusiasm is indeed contagious. “Are you a champion for the service of education?” he asks.

“If you are, the teachers and the children that you serve will trust you. They will feel it in your soul. They will feel it in your voice. And then they will allow you to push them out of their comfort zones.” It’s just like teaching, he says. Kids will follow the lead of an enthusiastic teacher; a district will follow the lead of an enthusiastic superintendent.

McCahill is quick to point out that enthusiasm doesn’t mean what he calls toxic positivity—pretending everything is going great when it’s not. “Just saying that everything is great and awesome—that becomes tone deaf after a while if there’s no substance behind it,” he explains.

So McCahill works hard to make sure his enthusiasm is specific—that he’s not spreading vague platitudes, but celebrating the unique qualities that make Nanuet shine. “We value these traits, the Knights traits, that make us something special,” McCahill says. “I believe superintendents should be able to rattle off a million reasons to be excited about the community they serve, if asked at any moment in their career. I better be able to explain what makes it so special to be in Nanuet.”

Of course, from a leadership standpoint, that also means making sure there are victories to be excited about. A culture of enthusiasm needs a strong foundation of pedagogy, communication, and excellence if it’s going to thrive. “But I believe equally as important as sound research-based practices is making your school community a place of creativity that connects people beyond just a dissemination of content and curriculum,” he says. “It’s the enthusiasm for community, for something bigger, that connects us. That’s the glue.”

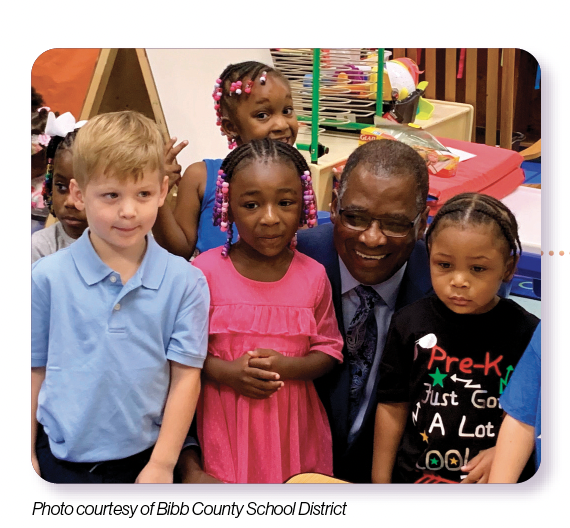

Dr. Curtis Jones took a roundabout path to the superintendency. After graduating from high school, Jones joined the United States Army and served in the Infantry for 20 years. He then returned to his alma mater, where he became a junior ROTC high school instructor. Now, in his 12th year in the superintendency and his sixth at Bibb County, he recalls how the military shaped his idea of leadership.

“I believe my military experience helped me in being an administrator by showing me how important it is to be a leader,” Jones tells us. “Leaders have to demonstrate that they’re here for something bigger than themselves—that they are here for the organization. People will follow you if they believe in you, if they trust you, and if they believe in your mission.”

This type of leadership has created a culture of growth at Bibb County. “Our belief is that when teachers join us, we’re going to help them grow and get better,” says Jones. “The best teachers want to work in the best environments with great coworkers. So we encourage teachers and staff to develop cultures where they are willing to grow and trust one another.” This environment has allowed teachers not only to feel confident in the classroom, but also to grow professionally. The district offers several programs to help teachers develop their leadership skills, whether they’re aspiring to leadership roles or already serving in them. “We believe that when we hire our teachers, we have to make sure we know where they want to grow,” Jones tells us.

Not only does Bibb County offer support to seasoned teachers, but they also make it a point to mentor and grow new educators. The district works with local universities to invite senior College of Education students to teach in Bibb County as teachers of record. Once they complete their bachelor’s degrees, they’re offered full-time positions. “We pay them a stipend, and we pair them with a master teacher who supervises them,” says Jones. “We want to give new teachers the opportunity to take on responsibility and to share what they’re thinking. And, in some cases, it helps us keep them in our system because they like where they are, and they see the support we give.”

All of these programs fall under Bibb County’s mission of being a Victory in Progress, or VIP. This idea is ingrained in every aspect of Bibb County, from the district’s strategic plan to the pin Jones wears on his lapel. “Our strategic plan is called Victory in Our Schools, but everyday we are a victory in progress,” he says. “Victory in Our Schools isn’t just a strategic plan—we talk about our goals every year and we meet with staff throughout to brief us on how they’re implementing it. We’re always looking at what our needs were, what we’ve actually accomplished, and what we can do to improve.”

This culture of improvement and growth has helped Bibb County’s staff understand the importance of their work in and outside the classroom. “For us, culture is the experiences people have and the beliefs they get from those experiences, which determine the actions they take,” Jones tells us. “If you have students who are not learning, you have to look at the experiences you’re providing them.” He believes that once staff see a problem, they must first own the solution and then solve it. “This allows teachers and administrators to be proactive,” he says. “It’s a continuous process that we expect teachers to do, but in some ways want students to do as well.”

The VIP mentality is not only growing among staff, but also inspiring students. “When we started passing out our VIP pins to our teachers, I had a third-grade student ask me, Are you a VIP?” Jones says with a smile. “I said, Well, I guess I am. And he looked at his friend and said, He’s a VIP! Then he looked back at me and asked, How do you get to be a VIP?”

It’s those small interactions that prove to Jones that the district’s culture of growth is thriving. “These moments remind me of when we were first trying to change the culture in Bibb County,” he reminisces. “And I think we’re getting there.”

“Leaders have to demonstrate that they’re here for something bigger than themselves—that they are here for the organization. People will follow you if they believe in you, if they trust you, and if they believe in your mission.”

SchoolCEO is free for K-12 school leaders. Subscribe below to have a digital copy of the most recent edition of SchoolCEO sent to your inbox.