Dr. Martin Bates: School Culture and COVID

We spoke with Dr. Martin Bates of Utah’s Granite School District to learn how he’s preserving school culture amid our current crisis.

This year has been a whirlwind of epic proportions. You’ve had endless meetings on crisis communications, fielded phone calls from confused and scared parents, and become an amateur virologist—all while moving your schools online for who knows how long. It has no doubt been stressful and sometimes exhausting. That said, many school leaders we’ve talked to have seen silver linings throughout this unexpected ordeal.

For Utah’s Granite School District, the transition has been a vital learning experience—in terms of meeting student needs and maintaining a strong school culture.

Granite is the third-largest school district in Utah with around 67,000 students in 90 schools. Since 2010, the district has been led by Dr. Martin Bates, whose focus on high standards and knack for connecting with his community earned him the title of Utah’s 2016-2017 Superintendent of the Year.

We caught up with Dr. Bates to find out what he’s learned through this experience and how he’s maintaining a strong culture of connection as we all prepare for an uncertain return to school this fall.

Can you tell us about the culture in Granite?

Some years ago, we adopted what we call The Granite Way. We teach the curriculum in instructionally sound ways, measure kids and involve them in their own learning, and have systems in place to catch kids who are falling. That’s just the way we do our business. And over eight or nine years, we’ve really been able to build that culture. We’ve worked to incorporate that into all of our conversations. I’ve heard that some of the schools have betting pools on how many times the term Granite Way will be used in a faculty meeting.

The Granite Way

- Fidelity to the core

- Use of instructional framework

- Use of instructional and assessment tools

- Professional learning communities

- Multi-tiered systems of support

I also make sure to personally interview all applicants for administrative positions—upwards of 90 people who are competing for what may turn into only eight or so positions. And that’s just because, again, I think school leadership is the most important part of all this.

I also make it clear to my administrators that they represent me in the schools, and that helps. They feel that weight on their shoulders; they are an extension of me. And that’s not because I’ve got a big head, but because that’s how you keep everybody together on the same page, moving in the same direction. I work hard to help people see where they fit—not what their job is, but what their role is—and then empower them to do that.

How do you establish culture in the district?

I really think the superintendency, as a position, has changed over the last decade. I’ve got to establish the culture, and I can’t do that by memo—at least not the culture I want. I want to establish a culture of engagement, of communication, of back-and-forth. To do that, I’ve got to make myself available.

Specifically, we’ll do Walk-In Wednesdays. When we started doing those a decade ago—on the first Wednesday of every month—we’d have a line of people. Nowadays, nobody comes. People will frequently call to ask if I’m still doing it, but they don’t sign up. It hasn’t been a packed house in several years, but knowing it’s available is enough for many of them. It speaks to a culture I’m trying to model for my principals, who are modeling for their teachers. Most parents don’t have teaching licenses or administrative licenses, but they all know their kids and their communities better than we ever will. So it’s really a partnership. We bring pedagogical expertise to the table, and they bring knowledge of their children and community. We’re not in charge. We don’t have the corner on this market. We’ve got to work together on these things. To have that kind of expectation, I’ve got to model things the way I do.

We also hire 300-400 new teachers every year, and at the beginning of the year, they all get together and I spend an hour with them. I tell them a folksy story, and I introduce them to the Granite Way—This is our mission, our direction, and where we are going. They get that from me firsthand. I really meet with every teacher and lay down what I expect.

Every year we also have an administrative kick-off where I spend an hour in front of all of our 180 administrators. We talk about where we’ve been and our focus for the coming year. And they’ve finally figured out that my mid-year evaluation questions are typically based on what I talk about the first week of August, so they pay more attention now. Because this really is the direction that we’re going. We mean this.

It doesn’t sound like a big deal until you work out the logistics, but I also spend an hour with every one of our principals in their offices, going over their data. We send out ahead of time what questions I’ll ask, and then I go in and spend time with them on their turf. Usually, we spend 30 minutes or so talking about different things—it’s not just a look-at-the-charts kind of talk. I get to know them personally a little bit. And then, in the last 20 minutes or so, I say, Who deserves or needs a pat on the back? They pick a few teachers, and we step into their classrooms so I can whisper into the teacher’s ear that their principal says they’re doing a fantastic job. I tell them two or three specific things, and then they just glow. Some of them even cry. That’s a way I try to establish our culture.

How do you build support for teachers in your district?

I talk about them as experts—the very things I’ve said to you, I say in these town hall meetings. For each of our eight high schools, I’ll go spend an hour without an agenda and take questions. When we’re talking about teachers and collaboration, that’s the way I talk about it. I say, Your teachers really are the pedagogical experts in the equation—but it is an equation. You guys are the experts in your children and community. When we add those two things together, we have the best outcome for your kids.

But then I really need principals to talk with their teachers that way, and I need teachers to step up and actually act the part. I share pointed examples with people from time to time, because angry parents will send me things teachers have sent them. And I’ll say, This can’t be the way we portray ourselves. When you send something out to parents with spelling or grammar errors, you can’t call yourself a pedagogical expert; you’ve just lost credibility. You’ve got to live it, you’ve got to do it, you’ve got to be it. Then, you’ll get the respect that you deserve.

What's your role as a leader, especially during a crisis like COVID-19?

You’ve got to be upbeat. You’ve got to be optimistic. This too shall pass, you know. It’s my observation that you can walk into a school and know what kind of leaders they have just based on the feel and the ambiance of their schools—whether this is a positive, constructive, happy kind of place or an oh my gosh, we’re dragging kind of place. It’s all about leadership; it’s all about the attitude and culture that flows right out of the leader. I see that in schools, and I try to do that same kind of thing at the district level. I try to communicate a lot, too. And I try to be positive and fun and have a can-do attitude. We’re the professionals, we know how to do this, but also we can rely on one another and have each other’s backs.

You've built a great repuation with in-person interactions — how have you maintained that through remote learning?

One of the problems about making yourself accessible is that people access you. I get lots of emails and communications from lots of people that I try to respond to myself, but I farm some things out to my staff when I need to.

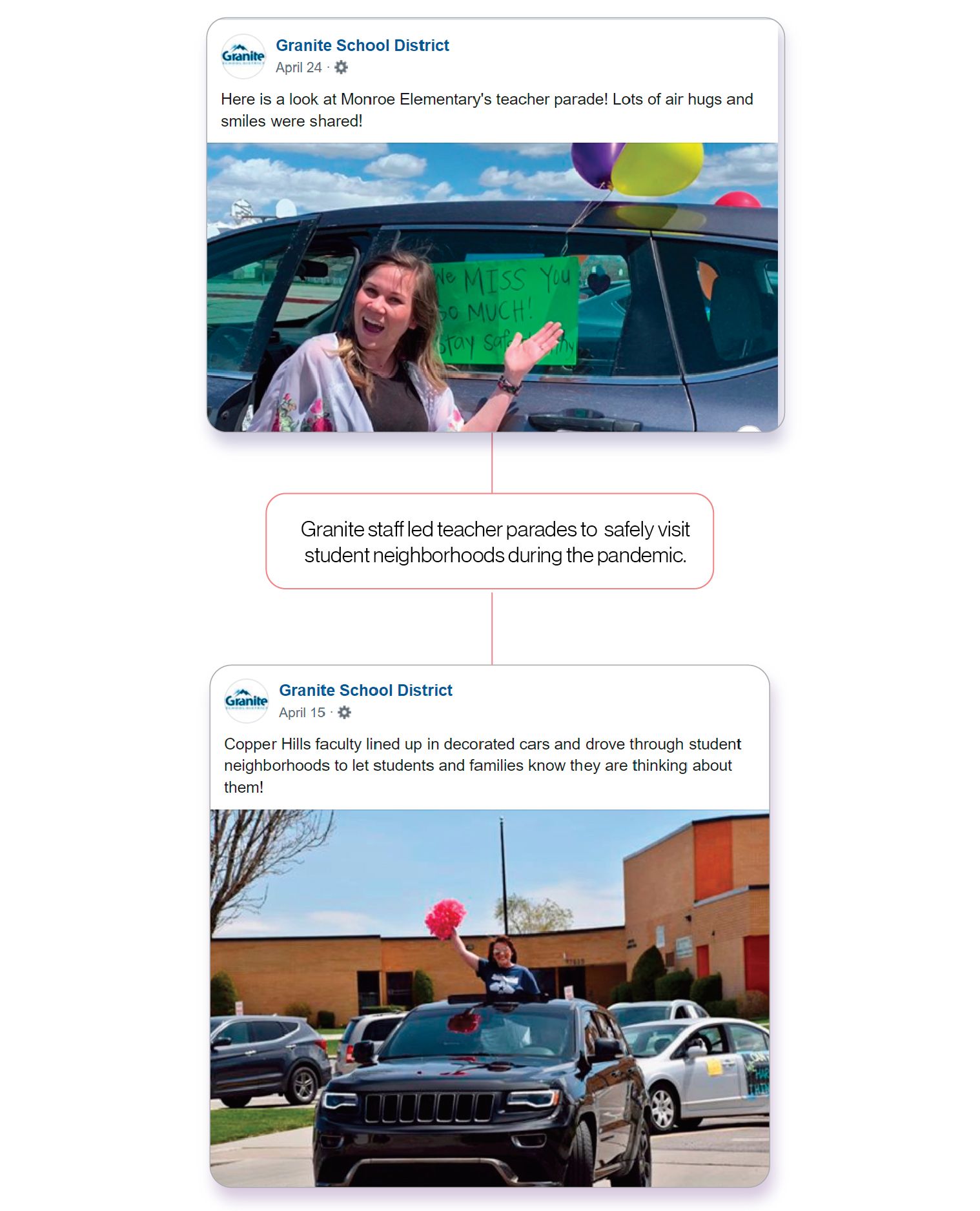

We’ve also been utilizing more of our social media platforms and trying to be a lot more responsive in those places. We’ve beefed up a lot of those avenues as well to try to have that two-way communication that we don’t get in the more traditional platforms. Our communications director, Ben Horsley, does all of that work. He’s a wizard with that. If there’s a message to superintendents, it’s this: get somebody confident, someone you trust, to run communications. I don’t have to look over his shoulder and worry about him. He’ll ask me from time to time what I think about this or that, but mostly we’re on the same page. I trust him. That kind of help is such a benefit for a superintendent.

Can you describe the experience of scaling a school system online?

Utah’s really lucky—the state funds an internet infrastructure, so all of our schools have had a lot of connectivity for years. Right now we’ve got more devices than we have students. We sent Chromebooks home, but more than 60% of our kids qualify for free lunch, so there were concerns about connectivity and equity. So we sent buses that were mobile hotspots out to different neighborhoods. We really worked to give all of our kids access. During those last two months of school, almost all kids engaged online at some point.

I’ve argued with our legislature for years—they’ve said, We just need to buy the right computer programs, and that will resolve any class size or teacher shortage issues. Now, I don’t think we’re going to hear those voices for a long time, because parents and families have found out that 100% online learning is not the most effective tool for the vast majority of kids. I know there are some—we’ve had a distance education department for several years that gets utilized quite heavily—but very few want to be 100% online. Online learning is a great supplemental tool and a great communication tool, but kids learn best in a classroom with peers and an engaging teacher guiding them.

I anticipate that we’ll be back in the fall, but I bet 15-25% of families won’t send their kids back yet. We’re talking through different models depending on different possible situations.

How do you advise your teachers on maximizng time with students online?

I don’t think that conversation is any different in a compressed, COVID environment than it would be in a regular one. Another lesson we’ve learned is that when people are focusing on the standards and objectives, it’s freeing. They find all kinds of time because they aren’t doing the extraneous things.

The counterpoint is that teachers may say: Then we don’t get to do our beloved activities. And I appreciate that. But, let’s say November is coming up and we want to do all these Thanksgiving activities that we’ve always done—that’s the wrong way to think about this. The right way to think about it is: what standards and objectives do we want to teach in November? Now, having identified those standards and objectives, how can we use Thanksgiving activities to teach those objectives? We do the same beloved activities we’ve always done, but they’re just much more targeted. We’ve got to start with the standards and then overlay activities based on those. You start getting flexibility and time and freedom because you’re focusing on what we’re here to do, rather than just filling the time.

How are you preparing for school's return in the fall?

We fully anticipate both in-person and distance instruction for all students. Whether we have a staggered schedule to increase social distancing or a full-time schedule with other restrictions in place, we are hopeful for as much in-person instruction as possible.

Many of our kids live in poverty, and it’s important for them to eat at school, because when they don’t eat there, they sometimes don’t eat at all. So maybe that means alternating morning and afternoon schedules, with an overlap at lunchtime so everybody can get a meal as well as class time. But that starts to play into our state’s required number of hours and days. There have been waivers for this year, so we’d need those for the next school year, too. We’ve got to think that through and see how it works, but I’m confident the state will work with us.

What will make some of this interesting is Granite School District being so large. We have seven municipalities and an unincorporated county, so we work with eight different governmental entities. We’ve got eight schools—high schools and their feeders —and six of them are in what Utah calls the Yellow Phase, which means they are low-risk, and the other two are in the Orange Phase, meaning they’re at moderate-risk. So, what happens there? We are in the midst of a formal survey of our parents on a variety of options that we are considering for this fall and hope to publicize some firm plans in the next few weeks.

We’re going to have fun with this—we can do it.

SchoolCEO is free for K-12 school leaders. Subscribe below to have a digital copy of the most recent edition of SchoolCEO sent to your inbox.