Report: The State of Cyber Schools

There's trouble in one of the fastest-growing trends in education.

Trouble in one of the fastest-growing trends in education.

“Can you see me?” asks a little girl with braids in her hair, sitting outside on her picnic blanket. It’s a sunny day. Uplifting music plays in the background. The clip cuts to a boy flipping through books in a library. “What do you see when you look at me?” he asks.

As the music builds, kids of all ages play outside, model clay sculptures, or laugh with friends. All of them ask variations on the same questions: “Do you see what makes me unique? Do you see what makes me brilliant?”

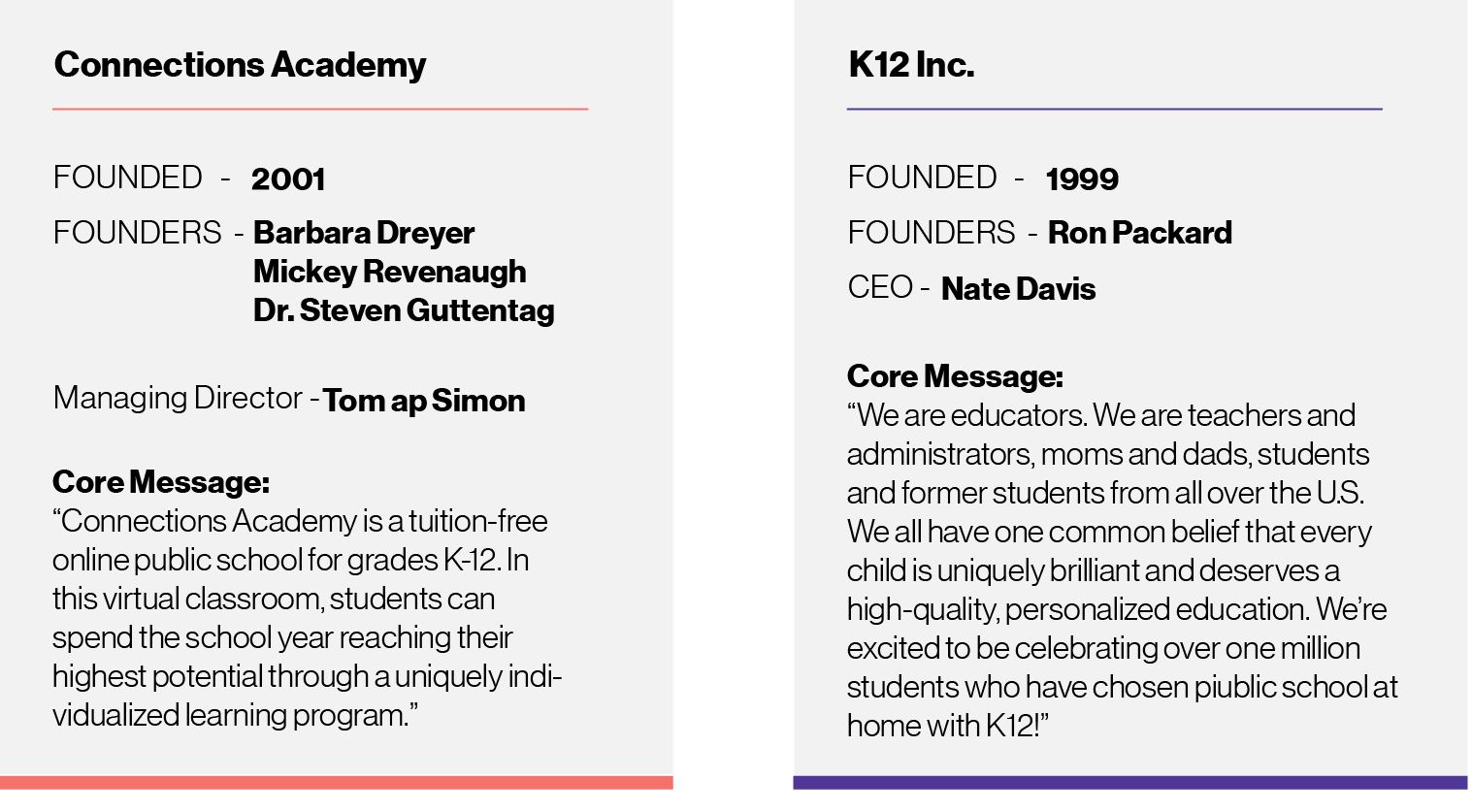

In this commercial, K12 Inc., the country’s largest cyber education company, paints a compelling picture. Asking the audience to consider what makes each child “uniquely brilliant,” they offer up their tuition-free, online public schools as a space for that brilliance to thrive. With its abundance of sunshine and smiles, the ad makes virtual education look like an experience worth buying into.

Ads like this one seem to be working. In the 2016-2017 school year, full-time online learning programs enrolled around 300,000 students nationwide.

Virtual School Growth 2011-2016

Almost half of those students are enrolled in schools powered by two for-profit companies: Connections Academy (owned by Pearson Education) and K12 Inc. Obtaining charters from the state, these education management organizations, or EMOs, operate their online schools, hiring principals and making calls on curriculum.

Virtual Schools' Enrollment Share by Provider for 2016

But the true picture of cyber schools may not be as sunny as their advertising suggests. While the most recent academic reports show improvement in their ratings, cyber schools have proven ineffective for the vast majority of enrolled students.

A 2015 report published by three independent research institutions, including Stanford’s Center for Research on Educational Outcomes (CREDO), indicated that some online students were essentially losing “72 days of learning in reading and 180 days of learning in math, based on a 180-day school year.” In other words, these students were performing as though they hadn’t attended math classes for an entire year. Virtual students spent the same amount of time with a teacher in a week as traditional public school students did in a day.

K12 Inc. issued a statement contesting CREDO’s methods, but the research on full-time cyber schools is damning. In their annual report on the national landscape of cyber schools, the National Education Policy Center (NEPC) consistently records poor academic results. According to the NEPC, only around 37% of full-time cyber schools received acceptable performance ratings in 2017.

Dr. Gene Glass, a research professor at the University of Colorado at Boulder, summed up the issue in an interview with SchoolCEO. “The impersonal laptop on the kitchen table is just not delivering an adequate education,” he said.

The Promise of Online Schools

For some students, online learning is essential to their education. Lexxus, a girl who developed an aggressive bone disease in elementary school, attends a virtual charter in Oklahoma. Without the opportunity to take classes online, she would have struggled to graduate; her parents needed the extra support provided by the charter program. Isaac, a student with autism, had trouble navigating class changes. The online format allowed him to continue his education without interference.

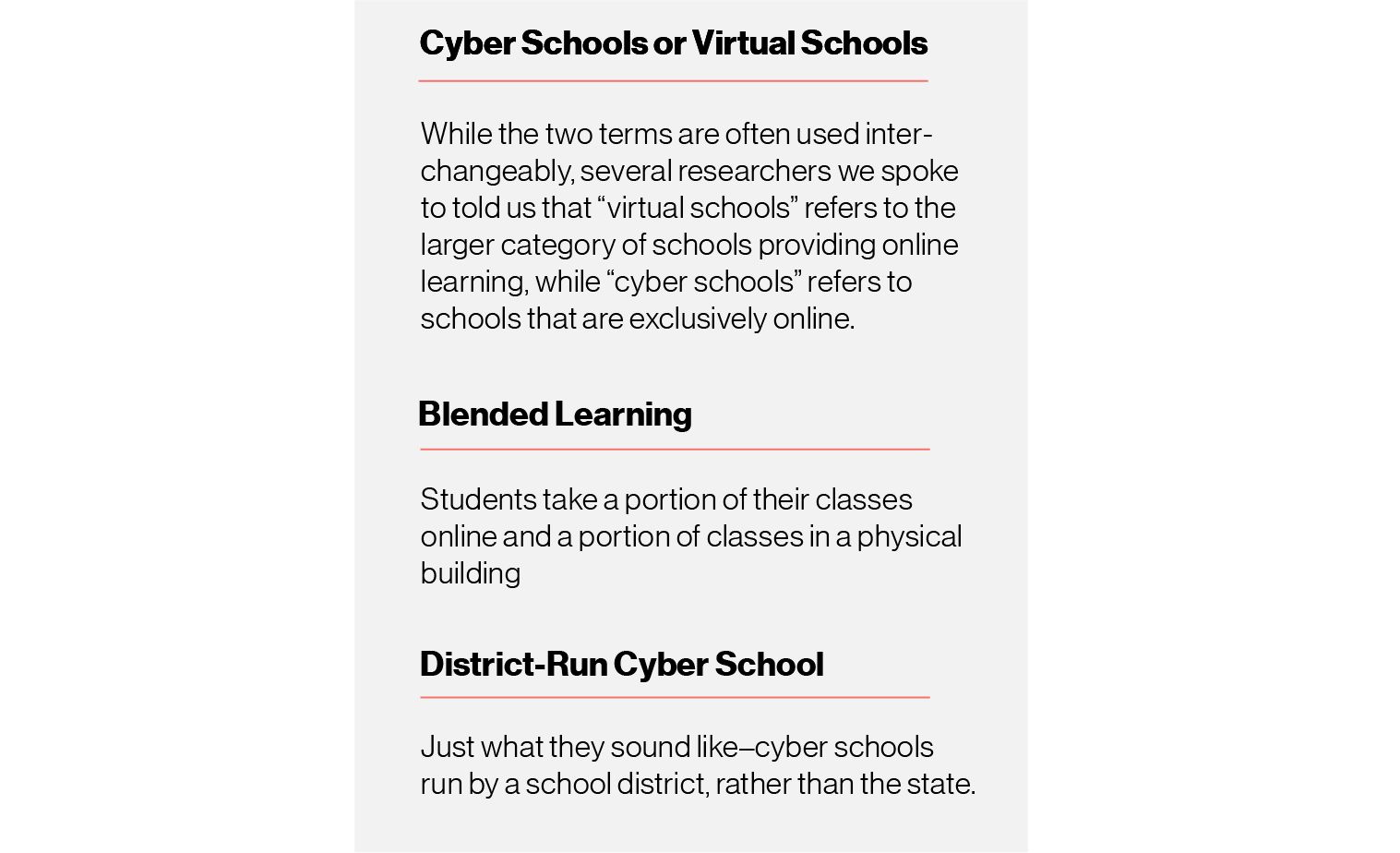

And over the years, more successful models of online education have emerged. The blended learning model, in which students split their days between online work and time in a physical classroom, earns moderately higher academic results than cyber schools alone.

For example, Dr. Michael Barbour, Associate Professor of Instructional Design at Touro University California, mentioned a blended learning facility in Michigan that is successfully serving a previously overlooked group of students: those who have been incarcerated. Teens in the Virtual Learning Academy have a few key advantages over traditional cyber students. Before enrollment, prospective students get certified in online learning skills, which also allows faculty to determine the type of online learner they are—and if online learning is indeed for them. Since the program’s base of students often requires extra academic support, teachers are available on campus throughout the week to answer questions and offer help. The school assigns only two courses at a time instead of the traditional six in order to reduce cognitive strain, which better addresses the needs of their population of students.

As a result, dozens of students who might otherwise have fallen back into the criminal justice system are receiving their diplomas. All it took was focus on students’ needs. Some of the best blended learning programs can match—or in some cases, even surpass—results from brick-and-mortar schools.

Some superintendents are opening district-run virtual programs as another developing alternative to full-time cyber charter schools. Chalkbeat reported on a small school district in Indiana that was close to shutting their doors—until they added a cyber school option. Within a year, they tripled enrollment, saving the district.

Alternatives to cyber charters' full-time online learning model are gaining traction across the educational community. Anya Kamenetz, the head blogger for NPR Education, mentioned that schools might evolve to accommodate “work from home days,” implementing a more blended model. Many teachers are already “flipping the classroom,” says Barbour. Students watch a video of their professor's lecture at home and work on activities in class.

That being said, both district-run and blended learning programs are still often operated by larger companies like K12 Inc. and Connections Academy. And while blended and district-run virtual options show promise, the most common online school option is still full-time cyber schooling, which accrues the worst academic ratings.

Problems and Profits

So what keeps cyber schools from providing a quality education to the majority of their students? The first issue may be the nature of full-time online learning in general; few students are actually well-suited to be virtual learners. Dr. Gary Miron, Professor of Educational Leadership, Research, and Technology at Western Michigan University, explained that successful virtual students share several key characteristics: they are self-motivated, have a supportive adult in the household, and work in a structured learning environment. However, many cyber students don’t share these skills and advantages.

Breakdown of Cyber Schools' Enrollment, 2016-2017

But it would seem that cyber schools could adjust to accommodate different learners—by lowering student-teacher ratios, for example, or providing more personalized instruction—but most for-profit programs have gone in the exact opposite direction. As a result, schools operated by for-profit management companies are consistently racking up the worst academic scores.

Is there a link between the problems and the profit model? As we’ll see, some of cyber schooling’s largest weaknesses, like high student-teacher ratios and false claims of personalization, seem to be directly related to the push toward greater profits.

High Student-Teacher Ratios

According to the NEPC’s research, the average student-to-teacher ratio in nonprofit cyber schools in 2017 was around 34-to-1. Compare that to the average ratio for traditional public schools, which is 16-to-1, skewed slightly by low student-teacher ratios in remedial classes. The average ratio in for-profit cyber schools? 44-to-1.

“Their so-called teacher actually does the monitoring, and they will intervene if the child hasn’t done any work in two to three weeks. They’ll try to send a personal email,” Miron told SchoolCEO. "It’s just no personal contact.”

With the cost savings the online model provides, cyber schools could have some of the lowest student-teacher ratios in the country. Instead, they move in the opposite direction. “So not only are they saving money on facilities, transportation, lunch programs, student support services— they also save money on teachers, which is the biggest budget item right now,” Miron concluded.

The Myth of Personalization

Most online schools market personalization—it’s on the front page of K12 Inc.’s website. A look into online programs’ structure, however, reveals a fairly standardized instructional model.

Barbour took us through the organization of a typical lesson in a cyber charter program. Students start with a multiple-choice test on the material for the day. The instruction they’ll receive in the lesson depends on which questions they miss on this test. For example, a student who misses two questions about reptiles in a biology lesson will then receive material about reptiles. Another student who misses questions about both reptiles and mammals will spend their lesson on not just reptiles, but also mammals.

The material doesn’t change per student; students just get more or fewer questions depending on what they get right and wrong. The differentiation only takes into account students' prior knowledge—not their unique needs or learning styles.

“For all of the talk of the personalization or the individualization or the customization, these programs are fairly standard,” concluded Barbour. “You, as a student, are just a widget on this instructional assembly line.”

Like their high teacher-student ratios, cyber schools’ lack of genuine personalization goes back to a push towards cost-efficiency, and by extension, higher profits. Accommodating student needs in an individualized, meaningful way would demand more staff and differentiated curriculum tracks—both of which come at a cost.

Staying Alive

How are cyber schools continuing to grow when their students are historically unsuccessful? The success of virtual schools comes down to three factors: their high student turnover, their accountability structures (or lack thereof), and their marketing strategies.

Virtual School Performance by EMO Type, 2011-2016

High Student Turnover

It's difficult to track enrollment demographics for cyber schools—partially because students who drop out are often quickly replaced by new ones.

According to Dr. Luis Huerta, Professor of Education and Public Policy at Columbia University, some schools have churn rates of up to 50%. But in K12 Inc. call centers, Personal Admission Liaisons (PALs) usher new students through the door. “They're able to replenish these kids very, very fast,” Huerta said. “The churn rates of kids coming in and dropping out is astonishing.”

While cyber schools manage to keep their enrollments up, this high churn rate weighs down the traditional public schools who deal with the aftermath. The Milwaukee Journal Sentinel reported that 40% of students enrolled in virtual schools in Wisconsin eventually withdrew, got kicked out, or dropped out during the 2016-2017 school year. Many students were reabsorbed into brick-and-mortar schools, putting strain on their zoned districts. We see this same story repeated across the country.

This high turnover rate once again indicates that profit is taking priority over student success. These companies don’t seem to care whether they’re filling minds as long as they’re filling spots.

Lack of Accountability

ECOT’s story, while extreme, highlights many of the central problems with the cyber school sector, including its lack of meaningful accountability. Because the sector is relatively new, legislators haven't developed accountability systems to correspond with cyber charters’ unique structure, an issue which played into the scandal. Since Ohio's legislation concerning online student attendance was muddled, ECOT was able to claim not to have attendance records when the state eventually demanded them.

These gaps in accountability are particularly glaring when you consider the amount of funding cyber schools receive. In 2011, the Virtual Public Schools Act became law in Tennessee. Written by the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), a prominent conservative policy organization, the Act ensures that cyber schools are "provided equitable treatment and resources as any other public school." This means that cyber schools receive the same funding as brick-and-mortar schools—without having to pay for the proverbial bricks or mortar.

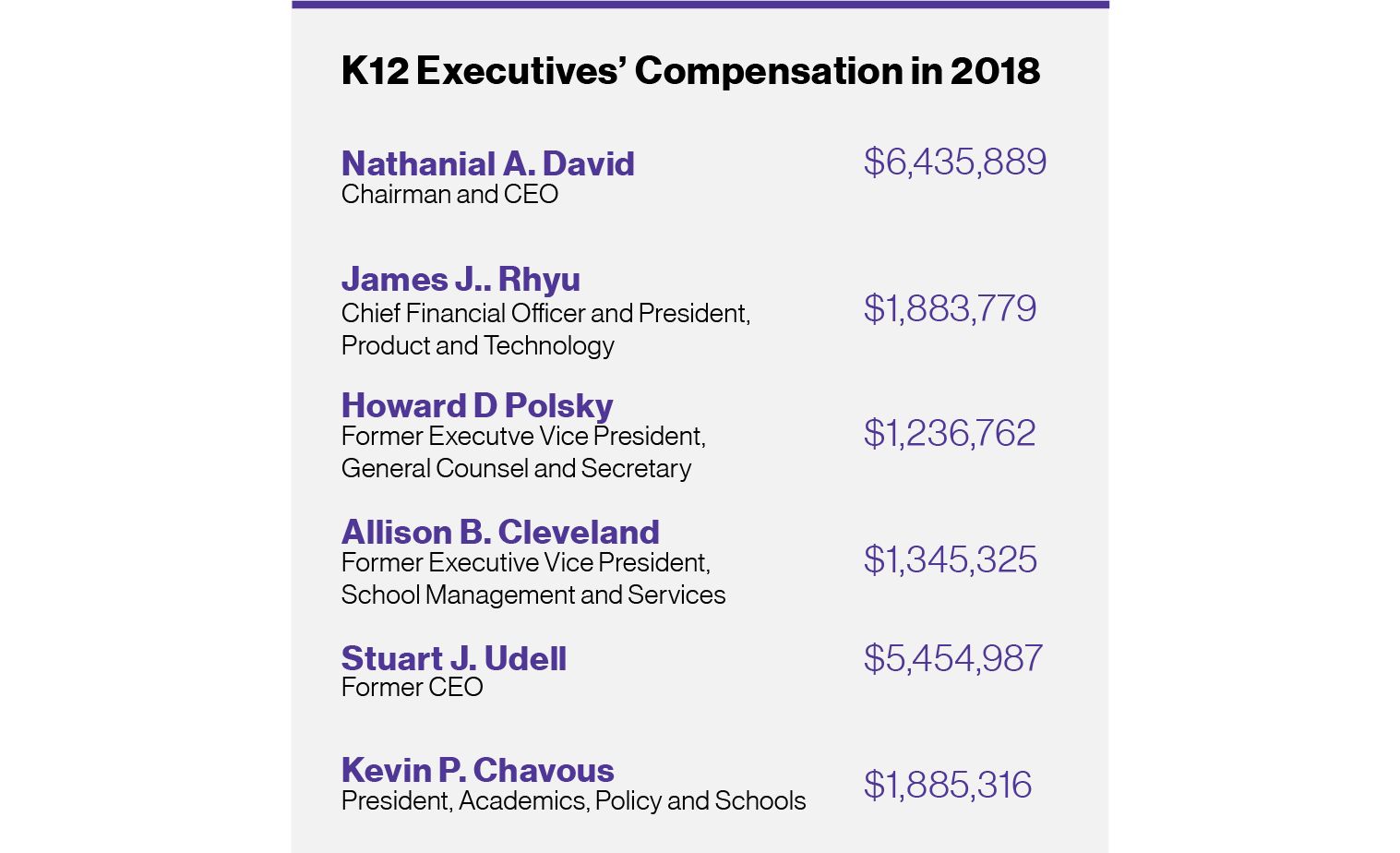

So how are they spending that money? K12 Inc., for one, paid their executive team a total of more than $18 million in 2018, according to its annual proxy statement to the SEC. They're also spending money buying out shareholders. In May 2018, K12 Inc.'s board of directors authorized a buyback of 1.83 million shares, at a purchase price of $27.5 million. They funded the buyback with cash on hand.

As Miron put it, “it’s hard to serve the interests of taxpayers when, at the same time, you’re serving the interests of stockholders.” With few accountability structures in place to keep cyber schools in line, it's easy for them to focus more on their business interests than their students.

Experts like Huerta point out that the huge differences between brick-and-mortar and cyber schools—from their teacher-student interactions to curriculum—should demand that they answer to different policies. “These distinct mechanisms require the development of new accountability systems if policymakers are going to continue promoting virtual schooling,” Huerta said.

At least publicly, K12 Inc. and Connections Academy appear to agree. They have each called for more specific accountability structures for virtual programs. Some of the researchers we spoke with, however, weren't convinced of their sincerity. Glass, who’s been covering virtual charters since their creation, was incredulous. “These companies are just running a scam,” he said. “They don't care about whatever the kids want; they just want to collect money from the state.”

Looking into financial reports and investigations on for-profit cyber schools, his point is difficult to contradict. In 2011, the Washington Post reported that K12 Inc. consistently sets up headquarters in a state’s poorest regions. This allows them to collect the highest possible funding amount per student, even if the students themselves are zoned to higher-income areas. On a quarterly earnings call in 2018, K12 Inc.’s Chief Financial Officer told shareholders that for each student enrolled, the EMO earns an average of $7,183 in revenue. Again, these are tax dollars.

Lucky Charms Marketing

In our interview with Miron, he asked us a puzzling question: Why do Lucky Charms keep flying off the shelves? If you’ve ever tasted one of those rainbow marshmallows, you know the brand’s popularity has nothing to do with its nutritional value. In Miron’s view, Lucky Charms’ success comes from its marketing strategy.

“You don’t market Lucky Charms to parents, you market to children,” he said. “And that’s the same with these for-profit companies.”

When a student goes through a breakup, gets in a fight with a friend, or embarrasses themselves in class, the opportunity to finish school at home becomes more and more attractive. K12 Inc. and Connections Academy, ready with hefty budgets and experienced marketing teams, pounce on those insecurities.

According to a 2012 study by USA Today, some for-profit cyber companies leverage millions of dollars in advertising budgets—and they spend that money targeting students. The study noted commercials on Nickelodeon and Cartoon Network, as well as ads on social networking sites for teens.

Today, advertisements for cyber education run on the radio, on Facebook, in the margins of websites, even on tour buses. And they work. “The marketing instruments of these organizations have been extremely successful in enticing a lot of applicants to enroll in virtual schools,” said Huerta.

The “Lucky Charms” approach is powerful, but it’s not the only marketing tool at cyber schools’ disposal. To give public school leaders an idea of who they're up against (and which ideas they can use themselves), we've analyzed the largest cyber charters' marketing strategies in "How to Out-market Cyber Schools.”

The Takeaway for School Leaders

Unfortunately, cyber charters aren’t just failing to provide their students with a quality education; they’re detracting from the experience of traditional students as well. Cyber schools play into an issue facing public schools nationwide: increasing competition due to school choice policies.

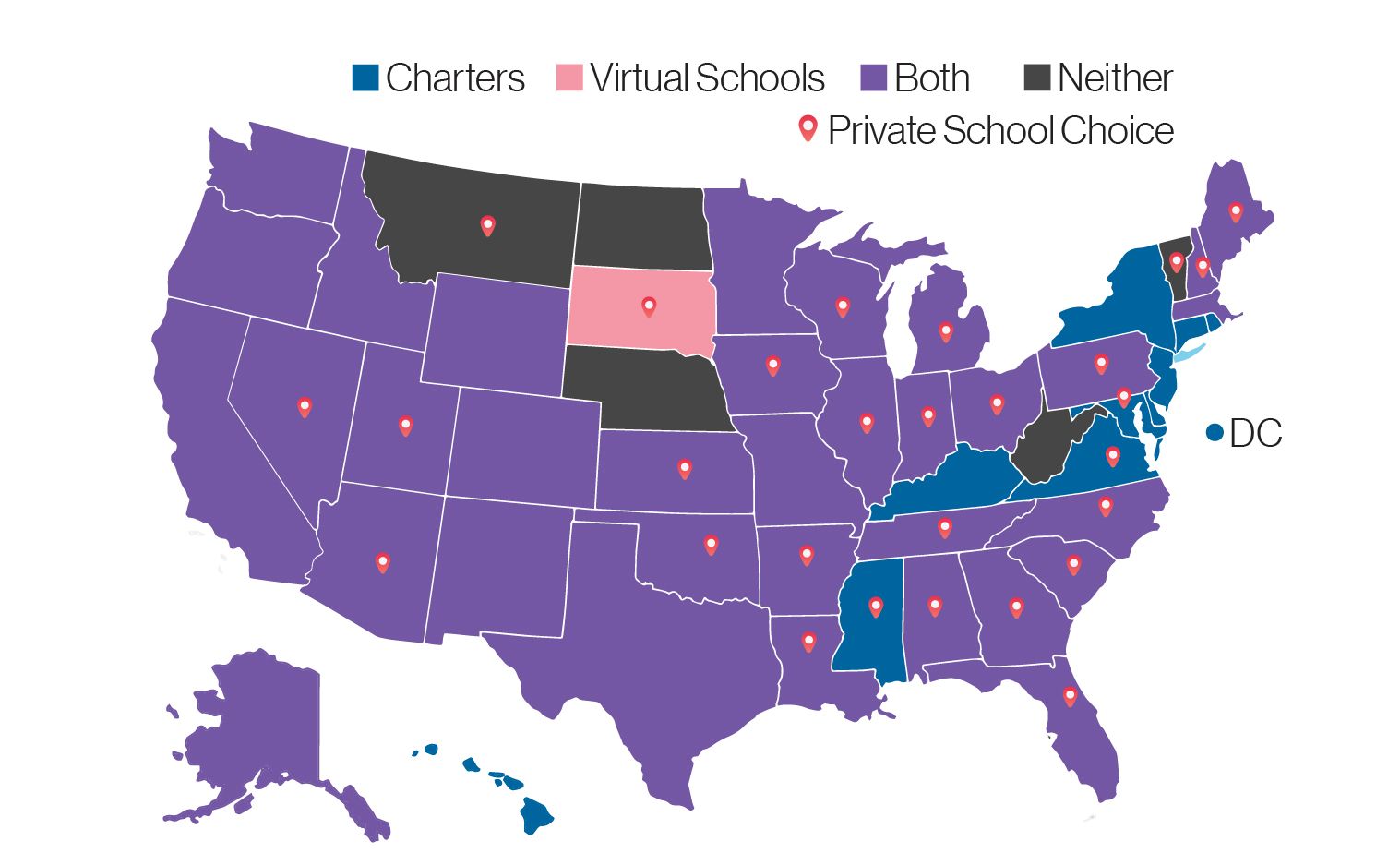

School Choice in the United States

When students transfer to the next district over—or a cyber school—they can pull as much as $20,000 in funding with them. Of course, it costs just as much to keep 350 students in an air-conditioned building as it does 400, but a lower enrollment means less money to pay for that air conditioning.

Keith Richards, a former superintendent from Newark, Ohio, lost an average of $350,000 each year to students enrolling in ECOT. “We actually broke that down,” he told Mother Jones. “And we’re talking about four teachers [for each of those years]. We’re talking about whether we have aides for special-needs kids.” The district ended up canceling high school busing and implementing pay-to-participate activities.

We consulted experts in cyber education on how they would advise school leaders to respond. Their answers varied from debunking the myths about cyber charters to exploring alternative online learning opportunities. The most prevalent advice, however, was to market the community aspect of brick-and-mortar education.

The Public School Advantage

Traditional public education is rooted in community. From the first public schools—one-room schoolhouses built and run by community members—to our current districts, a great school is the centerpiece of the neighborhood, even the town.

“Your strongest weapon is always going to be your community and your relationships,” said Kamenetz. “In rural communities, the schools are really important hubs.”

In a brick-and-mortar school, children sit side-by-side with next-door neighbors or friends from church. They meet kids from different backgrounds than themselves, broadening their horizons. They learn to socialize. They become invested members of their local community.

“We do a lot of things in public schools,” said Miron. “Our goal is not just to educate [students] in terms of math and reading, but to socialize them. It’s also to prepare them for productivity; it’s also to prepare them as citizens.”

Cyber schools, as they currently stand, not only fail to provide quality education—they offer fewer opportunities to connect. Without these opportunities, these kids aren't learning the crucial interpersonal skills they'll need in their adult lives. Of course, as we've mentioned, some children genuinely need an online option, whether because of chronic illness or other factors.

Perhaps over time, cyber schools will adapt to provide more civic and social engagement. As we've seen, blended learning programs might offer both the online option some circumstances demand and the social engagement that students need.

K12 Inc. and Connections Academy offer after-school activities and clubs online, but participating in a "virtual puppy club" like the one marketed by K12 Inc. won't offer the same growth and learning opportunities as the teamwork of an after-school sports program or a quiz bowl club.

At its best, cyber schools’ marketing put students at the forefront of their campaigns. By focusing on the experiences afforded by public schools—the community, the relationships—school leaders can offer the unique competitive advantage of public education.

SchoolCEO is free for K-12 school leaders. Subscribe below to stay connected with us!