Dr. Deborah Gist: Radical Collaboration

How Dr. Deborah Gist is empowering families to rebuild the high school experience.

On a hot Florida day in the 1990s, several school buses rolled up to Northwest Elementary. On the pavement outside, a troop of second-graders stood alert—visors on, clipboards in hand—to welcome busloads of their peers from all over the city.

Dr. Deborah Gist’s students had been training for this moment for weeks. One of the visored second-graders looked up at her in awe, squealing, “They’re really coming!” As the visitors unloaded, Gist’s class sprang into action, welcoming students to an immersive field trip of the Tampa Bay Wetlands. They’d been planning this event all year.

It all started years earlier when Gist’s principal led her behind Northwest Elementary to a huge expanse of land: a mess of marshlands filled with tires and old mattresses, all surrounded by a tall chain link fence. “Just look as far as you can see,” he told her. “All that land belongs to the school.”

What happened next would start a trend for the Tulsa native; she took the opportunity and ran with it. “We restored the land over a couple of years and turned it into an environmental center,” she explains. Gist then led her second-graders to research the marshland and create the field trip experience, all by themselves—complete with trail markers and a full itinerary for their guests. The field trips were wildly successful.

During her eight years teaching in Florida and Texas, Gist was a champion for this type of experiential learning. In Texas, she led her elementary students to plan and execute a young authors conference serving 1,000 patrons. Students were responsible for the budget, the catering, the venue—and they stepped up to the plate. Gist recalls walking in on one of her second-graders negotiating with a vendor. “This little bitty thing was on the phone saying, Well, our budget is only $350,” she tells us. “She was totally negotiating with a grown-up!”

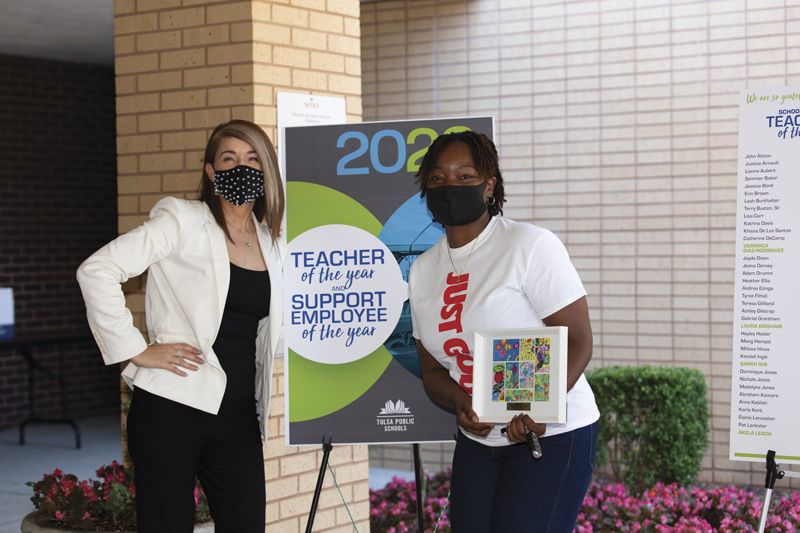

After her success in teaching—winning Teacher of the Year for her schools in both Fort Worth and Tampa—Gist went on to become Washington, D.C.’s very first state superintendent for education. In 2009, she landed a role as Rhode Island’s Commissioner of Elementary and Secondary Education, scoring a doctorate from the University of Pennsylvania along the way. In 2010, after just a year in Rhode Island, Gist was honored alongside Steve Jobs and Elon Musk as one of Time Magazine’s 100 Most Influential People.

Today, Gist is reimagining the process of making change in education. Back in Oklahoma, she’s currently leading the district she grew up in: Tulsa Public Schools. From elementary teacher to education commissioner to superintendent, she keeps the same unwavering focus on student success—always looking for ways to give her community ownership over their schools.

Organic Leadership

While Gist was in Rhode Island, the state’s education system managed to secure a Race to the Top Grant under the Obama administration. This $75 million grant took up a sizeable chunk of the state’s focus. “But we also had this little bitty private grant to do blended learning,” says Gist. It would be this grant, not Race to the Top, that put Rhode Island on the map.

To distribute the grant money, the state held a competition between schools. Only one school won the funding, but even schools who lost the competition kept experimenting with blended learning. “It became this grassroots movement,” Gist says—so much so that the state started hosting a conference to connect educators. “Teachers, school leaders, and students were teaching each other. It was the most beautiful, organic, true movement, led by people in the state who were passionate about that work.” In about two years, Rhode Island went from having very little blended learning to leading the movement nationally and even internationally.

But Gist learned more from the experience than new information about technology and personalization. “For me, the lesson was about who needs to be in the driver’s seat,” she says. “I’ve always been someone who believes in engagement. But there’s engagement, and then there’s more organic leadership—there’s a difference.”

Wow Moments

Coming from Rhode Island to Oklahoma, Gist was in for a bit of a shock. “I knew Oklahoma underfunded education, and teacher salaries were low,” she says. In 2020, Oklahoma’s per-pupil funding was about half of Rhode Island’s. “But I didn’t fully appreciate the depths of that, how competitive salaries are in neighboring states. And I didn’t expect for there to be additional cuts.”

The year before Gist took the role of superintendent, TPS started the school year with 75 vacancies. At best, classes were taught by substitutes; at worst, they were combined or cut altogether. “It was just unsustainable,“ says Gist.

At TPS, she’s done whatever she can to fill in the gaps. One year, Gist even drove to the house of a teacher who planned to retire, holding a fistful of balloons. “I told her, You can’t walk. We need you,” she says. “It’s that kind of effort.”

Throughout her time in Oklahoma, Gist has been a fierce supporter of teachers. When they walked out of classrooms to protest school funding in 2018, Gist marched with them. “They need to be paid like the professionals they are, and we are never going to stop advocating for them,” she tells us.

This kind of radical support is part of a larger cultural shift she’s leading in the district’s central office. “We are here to serve,” Gist explains. “That is the only reason this whole office exists.” To keep tabs on the district’s organizational health, Gist’s team conducts surveys focusing on her staff’s experiences: Are you supported? Do you have what you need? “We are not here to be roadblocks,” Gist says. “We want our educators to know that they’re supported.”

Over time, the data reports growth in district leadership. In 2017, central office administrators at TPS scored a 64%. But in the most recent year, teachers scored them 80%, and principals scored them 90%. For other superintendents wanting to make a similar shift, Gist recommends asking for frequent feedback from staff. At first, the TPS team conducted regular surveys, but then staff reported survey fatigue. Now, the team holds pulse checks: quick check-ins with employees that don’t add to their workload. However, Gist notes, a critical part of any sort of measurement is the leader’s response. “Use that information; respond to it; talk about it so people know that it matters,” she says.

But to Gist, really changing the culture of the team means going beyond service. “It’s not enough that we understand that we’re here to serve—take it a step further,” she says.

The TPS team has started practicing what they call wow moments. Say, for example, that you get a call from a teacher who’s having an issue with payroll. While they’re explaining the problem, they mention that it’s their birthday. You’re listening and helping solve the problem; that’s to be expected. But the next morning, you stop by their school on your way to work with a birthday card. “That’s the wow,” says Gist. “It’s going so far above and beyond that it surprises people.”

From Stakeholders to Changemakers

From the outside, one might expect Oklahoma’s budgetary restraints to restrict TPS’s ability to innovate, but Gist has seen the opposite. “They say that necessity is the mother of invention,” she says. “When you’re scrambling to run a system that’s underfunded, it can be hard to think about adding one more thing—but there’s actually more of an opportunity to innovate in those moments than in places where you have more adequate resources.”

Early on in Tulsa, Gist made a point to welcome all of her stakeholders as expert changemakers. “Too often, engagement becomes, Here’s an idea we came up with. Give us some feedback, and maybe we’ll tweak it—as opposed to authentic participation and ownership of the process,” she says.

Around three years ago, for example, TPS began to realize that its seventh-grade center wasn’t working for students. With only about a hundred kids in the building, the program was financially unsustainable. Students weren’t in the building long enough to build significant relationships, and cost restrictions meant that they didn’t have access to the same resources as their peers across town. Luckily, there were several solutions. Gist initially proposed that seventh-graders move to the 8th-12th grade secondary school to give kids stability and access to more programs.

The community’s reaction, however, was fiery: “This is a terrible idea. You’ve already made up your mind. It’s not safe,” Gist recounts. But there’s a larger reason families were mistrustful. “North Tulsa is a part of our city that has historically been oppressed—not represented in decision-making,” she explains. “There’s a lot of mistrust, because we have not served their children well for a very long time.”

Instead of forcing a solution forward, the TPS team turned to the experts: the North Tulsa community. The district formed a task force of community leaders, and TPS promised, in advance, to implement whatever solution the task force proposed. Gist calls the process “radical collaboration.”

The task force worked hard to produce a set of expectations—and they spanned beyond the seventh-grade center. Though many Tulsa middle schools are merged with the district’s high schools, the community requested that the district form a comprehensive 6th-8th grade middle school. They also requested high-quality extracurricular experiences and a resource center for families.

The recommendation came in February, and the task force challenged administrators to implement dramatic changes by August. And, somehow, they did. Today, the school offers a swimming pool, chess, debate, boxing, dance, and a parent resource center. Going into their third year, the same task force is still active and engaged, holding administrators to the highest standards. “It was beautiful and amazing, but it was also very daunting, and truly, I didn’t think it was possible,” Gist admits. “But you know what happens when you believe in impossible things? You can actually do impossible things—and we did.”

Making Innovation the Tradition

While it has been a strenuous project, the new middle school isn’t the only kind of innovation taking place at TPS—far from it. “We also have a small team of super amazing people who carry out a number of different efforts in the district,” Gist tells us. “We call it our design lab.”

One of the design lab’s most ambitious initiatives is Tulsa Beyond, a program that aims to redesign the high school experience. “I really believe that high schools have not worked for most kids for a long time,” Gist tells us. “There are far too many students, thousands and thousands right here in Oklahoma, who drop out every year. The ones who do finish school aren’t leaving with all the skills they need to be successful. The structure is not working.”

In Tulsa, Gist has had the opportunity to do something about it. “What we wanted to do was reimagine the high school experience. And we didn’t want it to come from administrators—we wanted high schools to be designed by the people who knew those schools the best.”

The team started with what’s known as discovery work: empathy interviews, focus groups, and surveys to gather data about high school. Though they cast a wide net—interviewing parents, community leaders, higher education professionals, and local business owners—they kept their focus on students.

Discovery work took about a year. “It’s a lot of manpower,” Gist explains. Each interview takes about two hours: 30 minutes of prep, an hour-long interview, and 30 minutes of data synthesization—plus travel time. To make sure interviewees felt comfortable, the district had them choose the location. In all, the team conducted about 150 interviews, and received additional input from around 5,000 stakeholders through surveys, focus groups, and student shadowing.

After the discovery work, the TPS team went into design—but not alone. “We took that information to the experts,” says Gist. Design teams were filled with students, parents, teachers, and school leaders at each of the high schools. For a year, teams pored through the data and constructed different school models. While each model needed to include a few basic factors—like academic proficiency and college and career readiness—design teams had the power to build the schools they envisioned.

Teams worked for six months on design and implementation plans. Finally, in the fall of 2019, they launched three brand new high school models. Each is anchored to a different focus, from project-based learning to life coaching.

At Hale Beyond, for example, students work in a room similar to a coffee shop, prioritizing self-directed learning. Some students meet one-on-one with a teacher; others work individually or in small groups. After students plan their days, they tackle different sections of the curriculum, organizing meetings with classmates and teachers.

Another high school, Tulsa Learning Academy, centered their model on both project-based learning and life coaching. Every teacher in the program has been trained formally as a life coach, and they mentor kids both one-on-one and in small groups.

Across the city, Webster Beyond emphasizes personalized learning. Students are placed in houses, Harry Potter-style, and participate in out-of-school volunteer work twice a month. “Already, in that first year of implementation, they were seeing really great results,” says Gist with a smile.

Constructive Turbulence

Gist’s innovation in Tulsa, while remarkable, isn’t a new topic of conversation for her. “I started teaching in 1988 in a city with a lot of need, and we were asking the same question: How is our school district going to serve kids who aren’t being served well by the system?” she says. “I refuse to leave this planet without having changed that conversation to: Look what we’ve done. What else can we do?” With any kind of innovation, things are bound to go wrong, but as Gist sees it, that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t take the chance.

Years ago, Gist boarded a tiny plane on the way to a meeting. “All of a sudden, there was this crazy turbulence—the worst kind, where the plane drops,” she tells us. Soon the bumps were too big to ignore. “At one point, the pilot came over the speaker to check in. He said, This turbulence is coming from a massive tailwind, so it’s actually constructive turbulence. We’re going to get there faster in the end.”

That short plane ride gave Gist a lesson she would take with her throughout her career. “When you do things that are new or when you’re striving for more, you’re going to have bumps along the way,” she says. “But at least it’s constructive turbulence. Those bumps are moving you forward.”

SchoolCEO is free for K-12 school leaders. Subscribe below to stay connected with us!