Multipurpose Schools

How community schools in California consider the needs of every student

For a hundred years or more, the American schoolhouse was the center of each town. These spaces did more than just educate children; they were anchors of their communities. Civic meetings, potluck dinners, spelling bees, you name it—they all took place within the confines of the local school. Today, however, schools don’t always hold quite the same space in their communities.

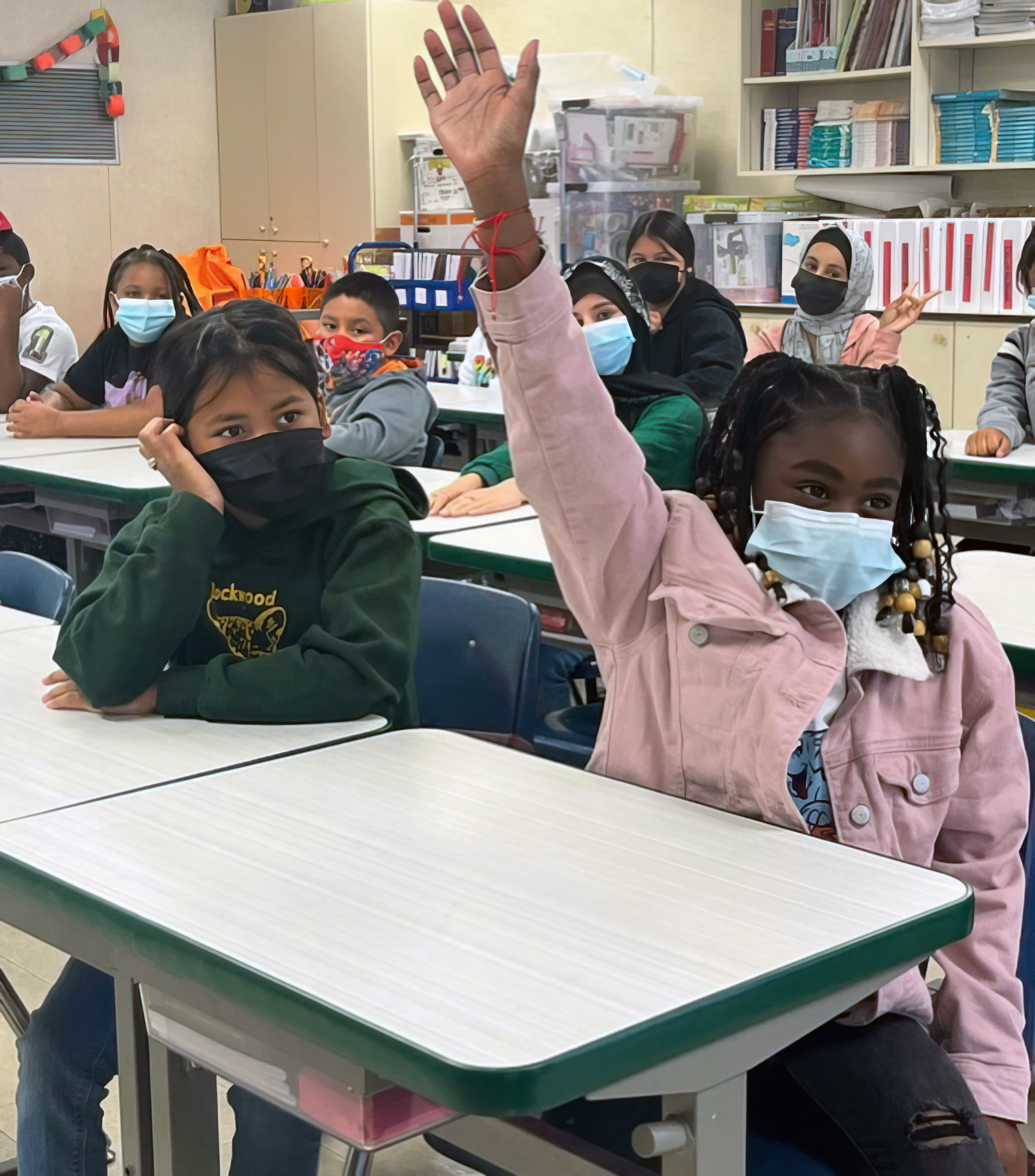

States like California are working to change that through the community schools model by incorporating wraparound services beyond their core academic offerings. If you take a walk around a community school, you might see a student getting a toothache looked at in a dental clinic (a la Los Angeles Unified’s Murchison Street Elementary) or parents studying English as a Second Language (like in Anaheim UHSD’s Sycamore Junior High). The overarching goal is to support the whole child. After all, schools cannot accomplish their mission without addressing the barriers students (and their families) face outside the classroom.

California’s legislature recently set aside funds for the biggest investment in community schools to date. The California Community Schools Partnership Program is awarding $649 million dollars in grants to districts with established programs as well as those just getting started.

While your state may not have the same funding opportunities, the values and experiences of those doing the work in California offer important lessons for anyone looking to implement community schools in their own districts. What’s more, you probably already have some experience in this work. Over the past few years, for example, schools have taken on the monumental task of feeding students regardless of whether they’re on campus or not. The promise of the community schools model is the opportunity to systematize the extracurricular supports your campuses already offer, allowing you to fully lean into supporting every learner’s needs.

The Four Pillars

In setting up their new program, policymakers in California have defined four values that make up a successful community school:

- Collaborative leadership

- Integrated student supports

- Family and community engagement

- Extended learning time

These four pillars describe how community schools should operate and what should drive their work. Integrated student supports, for example, encompass not just academic needs but students’ physical, socioemotional, and mental health needs as well. The form these supports take depends on the community. Campus leadership has one perspective on what their students need, but parents and learners themselves should also have a voice in what schools provide. That’s where collaborative leadership comes in.

Laying a Strong Foundation

“Relationships and collaborative leadership are the throughlines for community schools,” Aronn Peterson tells us. Peterson is the community schools coordinator for San Diego Unified, one of the California districts using state funding to launch their own community schools program. San Diego’s work in this area spans all the way back to 2020 with the creation of their Community Schools Implementation Team. This group laid the foundation by defining job responsibilities, ironing out funding details, and establishing how site coordinators will work with campus leadership.

This collaboration with building-level leaders is very important, argues Peterson. If there isn’t a strong sense of buy-in from principals and their teams, important work could wind up being siloed. Getting everyone on the same page involves connecting the work of community schools with the overall vision for each campus. The same can be said of the district as a whole. “The vision of community schools isn’t much different from the vision of most superintendents,” Peterson tells us. “How are we supporting our kids? How are we removing barriers? How are we building equitable systems? Those are the main tenets.”

Another important point is that there is no template for what a community school should look like. In San Diego, five campuses have been selected to be the district’s initial community schools—and each one is being treated as completely independent from the others. That’s because each school’s community is different. Stakeholders ranging from teachers to parents to students are consulted about their own unique needs.

The timeline for Peterson and his team starts with laying the groundwork in the first year. Internally, this includes training and learning as much as possible about each school’s respective community. Externally, the team conducts a needs assessment that includes the voices of the community, teachers, staff, and students. In Years Two and Three, the real work of addressing current systems and building new programs begins.

But the work of community schools isn’t about tackling every single issue students and their families face. The key is to focus on addressing the needs your community identifies as most important to them. “All is not always best; be strategic,” says Andrea Bustamante, Oakland Unified’s executive director of community schools and student services. “If the need is around mental health, find a really great mental health provider and make sure they reflect your community. It’s about balancing the right supports and services for your students.” The district’s main role is ensuring that the proper resources are there to support the work.

In San Diego, that’s where site coordinators and Peterson’s role as district coordinator come into play. This team builds connections with community partners who can help ensure each school’s success. And just because each campus is focused on their own projects doesn’t mean they’re working alone. The whole system is stronger because of the collaboration between site coordinators and the district. What’s more, San Diego is able to learn from other California districts already in the process of running community schools, such as Riverside Unified and Chula Vista Elementary School District.

In Oakland Unified, one of the state’s most established community schools networks, any campus has the authority to hire a community school manager. The district’s community schools leadership coordinator then helps principals through the hiring process. Bustamante tells us that these site coordinators come from a variety of backgrounds. Some are former teachers or social workers, while others have worked in family engagement or after-school programs. Many are also alumni of Oakland Unified. Whatever their prior experience, it’s important that these hires look and sound like the students—and communities—that they’ll serve.

From a Campus to a Network

Scaling community schools involves a few important factors. Aside from funding, the biggest key to long-term success is patience. The barriers to learning that create disparities in education outcomes haven’t cropped up overnight. As Peterson says, “We need patience to be able to build relationships, understand the issues, and then go in and problem-solve.” One year of attending a community school might not move the needle on a student’s test scores—but that’s okay.

Data on lagging indicators such as attendance levels and reading scores absolutely does matter—and improvements there will come with time. In the short term, what matters more is evaluating and responding to campus and community needs. How’s relationship-building going? What are family engagement and involvement like? The answers to these questions will hint at success in other areas down the road. This is where opening up strong lines of communication among building-level leaders, teachers, and families pays dividends.

Another factor in successfully scaling community schools within a district is the actual growth pattern itself. Which campuses become community schools—and when—matters for your district’s feeder pattern. It could be jarring if a student transitions from a community school to a traditional one. Continuity of services makes a difference. After all, a student’s needs don’t change when they move from one school building to another.

Part of that continuity of services also means setting up staff members at each community school for success. Peterson says one strength of San Diego’s approach has been the focus on capacity building. As part of their onboarding, all site coordinators are trained on the four pillars and what they look like for the district. This ensures they are ready to pursue the goals of the community schools model once they are enmeshed in their individual campuses.

What’s more, San Diego is piloting an instructional coach role at one school to work directly with the principal. The goal is to help campus leaders embrace the tenets of collaborative leadership, which are vital to the whole endeavor. At the end of the day, principals and community schools liaisons should work in concert. As Bustamante says, these employees “allow the principals to focus on learning and instruction while the community school manager helps with the other supports students need. That way, kids can get to the classroom ready to learn.”

In any implementation effort, there are going to be mistakes—strategies that don’t work out or don’t fully address the challenges at hand. However, any misstep is also an opportunity to learn, adjust, and pivot. Foundational changes won’t happen overnight, but that’s what the community schools model is all about. As Peterson describes it, “At its core, it’s about ensuring equity for our students. We’re removing barriers. We’re looking at fundamentally changing how we do school.”

Currently, 66 campuses in Oakland Unified (three-quarters of the district) have dedicated community school managers. The goal doesn’t have to be 100% adoption at the campus level, however. Over time, practices from community schools can become part of your entire district’s standard practices. According to Bustamante, Oakland views all of their campuses as community schools because each one now has a coordination of services team and an attendance team to support students. The work of making sure all students are successful doesn’t just belong to one position or department. Supporting students is everyone’s job, and that mindset can be a powerful motivator across an entire district.

Getting to Work

Whether today or tomorrow, there’s never a bad time to start building the relationships that lie at the core of successful community schools. However, when thinking about this work, remember that community schools are not an all-or-nothing endeavor. You don’t have to solve every problem; just focus on where you can chip in. Partner with the local health department for a vaccine clinic, or team up with a food bank to offer meals over the summer.

While the community schools framework may sound like something you’ll have to build from scratch, that’s really not the case. The good work your campuses are already doing for each and every learner is the starting point. Community schools simply offer a way to double-down by building a systematic approach to caring for students. With a little collaboration and an open mind, you’ll be well on your way to building even stronger bonds between your campuses and their communities.

Subscribe below to stay connected with SchoolCEO!