Loud and Clear

Successful student leadership initiatives have a few key components in common: processes, relationships, follow-through and inclusivity.

Loud and Clear

How Student Leadership Can Impact High-Level Decisions

If there’s one thing we know about educators, it’s that they believe vehemently in the power of education. But unfortunately, students aren’t always able to match that enthusiasm. In the 2021-22 school year, 30% of students nationally were considered chronically absent, and in a pre-pandemic Gallup survey, two-thirds of high school students reported feeling disengaged at school.

There are nuanced reasons for this reality—including everything from a loss of enrichment funding to the alarming decline in student mental health—and a number of those reasons may feel completely out of your hands. That’s why we’re here to remind you that getting students excited about school is possible. Research shows that one way to increase a student’s sense of self-worth, give them a feeling of purpose at school and improve their academic motivation is to give them a voice. So if you want to get students more engaged at school—try giving them a voice in their education.

Effectively implementing student leadership initiatives can be difficult; it can take significant time and effort. But, if done well, it’s worth it. Time and again, we’ve seen that the district-level initiatives that manage to include student voice successfully have four key components in common:

- They implement clear and organized processes.

- They cultivate meaningful relationships between students and adults.

- They highlight the importance of follow-through and district-level accountability.

- They prioritize inclusivity.

Let’s take a look at how these elements have played out in three different districts across the country. Maybe you’ll be inspired or—even better—see a way beyond some of your own hesitations.

Student Leadership in Denver Public Schools, CO

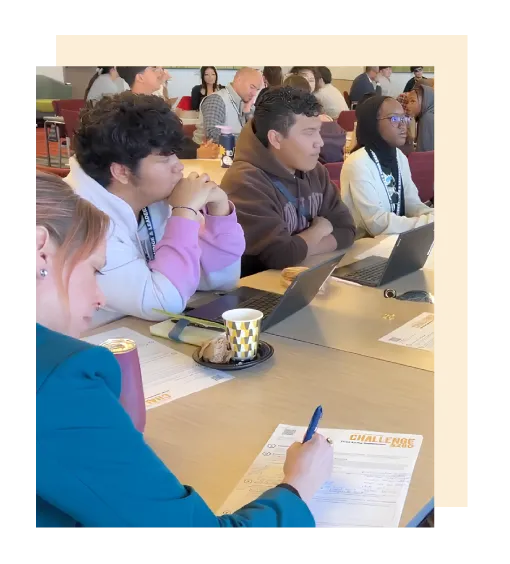

In Colorado’s Denver Public Schools (DPS), student leaders are spearheading progress—from leading a PD unit on culturally responsive teaching to implementing a curriculum review board for teachers to get student feedback. It’s all thanks to an innovative initiative called Challenge 5280.

According to the DPS website, Challenge 5280 is “an opportunity for student leaders to present policy solutions, facilitate educational workshops and generate a call to action for their school communities.” Rooted in a student-centered, project-based learning plan known as an action civics curriculum, Challenge 5280 is guided by a set of clear and repeatable processes proven to effect real change. The program is housed under the umbrella of DPS’ Student Voice and Leadership (SVL) office—which is itself an example of how the district centers student voice.

Every year, Challenge 5280 unfolds across three events. The first takes place in the fall, when students come together with experts in the community to deepen their understanding of a specific issue they’ve identified within the district. “Sometimes students are trying to address something that there’s already a solution for,” says SVL Director Magnolia Landa-Posas. “Maybe there’s already a resource out there, and their focus doesn’t need to be a policy change, but more of a campaign to educate the rest of the student body. Or maybe there are blind spots the students don’t know about. Maybe they have biases they need to consider.”

Students then move into the research and data collection phase of the process. Challenge 5280’s second event is the spring roundtable, where students meet with district experts to get feedback on their research process, data analysis and policy ideas. “We also see the roundtables as an opportunity for students to develop meaningful youth-adult partnerships,” says SVL Specialist Jade Evans. Those relationships are not only crucial to the work happening with Challenge 5280, but they’re also a way to, as Evans says, “create avenues for students to work directly with key power players in the district and community.” Finally, the third event is the culmination of all this work: the Challenge 5280 Summit. There, students propose the policies they’ve developed throughout the year.

One of Landa-Posas’ favorite examples of a successful student-led policy initiative resulted in the reunification of West High School. In the early 2000s, some of DPS’ larger high schools splintered into smaller schools that could be housed in buildings with free space. This meant that in some of the district’s buildings, multiple high schools operated under the same roof. During Landa-Posas’ first year with DPS, students said they wanted to focus on community-building because there was animosity between the two schools co-located in the West High School building. In their research, the students learned about the 1969 West High School Walkouts, in which a group of majority Hispanic students demanded better educational opportunities. Not only had West High School once been one unified school, but it had played a pivotal role in the history of student advocacy.

Learning this, the students decided that they didn’t want to be split anymore. They wanted to, once again, all be part of the same unified student body. So they pitched reunification, and the board went for it. “We sometimes forget how involved and central our youth were to making that happen,” Landa-Posas says. “Yes, the board technically made it happen, but all the legwork, all the community-building, all the reparation started with our youth.”

As proud as Landa-Posas is of what has been achieved, she’s also careful to remind Challenge 5280 participants that not every policy pitch will be successful. “We tell our young people that sometimes you might do a great piece of work, but there isn’t any appetite from the adults,” she says. Still, Challenge 5280 has seen enough successful policy pitches that student participants know they can rely on district leaders to follow through on their suggested changes when possible.

But perhaps the most special aspect of Challenge 5280 is its emphasis on inclusivity. Often, student leadership opportunities “privilege students who have performed well academically, who aren’t experiencing any behavioral issues and things like that,” says Evans. “But we really want to be open to any student who wants to participate. That’s why we don’t have any prerequisites or other requirements for participating in the program.”

“We do everything we can to ensure there’s no barrier to entry,” Landa-Posas adds. “And that’s important because the young people who are experiencing these inequities and injustices in the school system are most primed and knowledgeable when it comes to identifying solutions.”

Student Leadership in Napa Valley Unified School District, CA

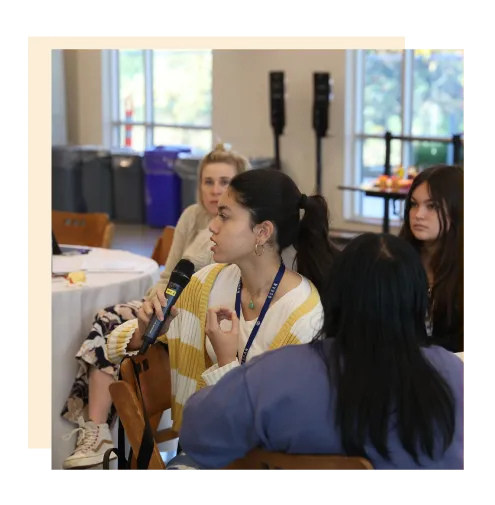

“Those who will be impacted by any change should have a role in shaping that change,” says Dr. Rosanna Mucetti, superintendent of California’s Napa Valley Unified School District (NVUSD). “We don’t want our vision and plan to happen to those who will be most impacted. We want them to create it with us.” Mucetti and Julie Bordes, NVUSD’s chief communications and community engagement officer, both knew students would be the ones most impacted by the district’s strategic plan. So, in partnership with consulting firm Prospect Studio SF, they carefully organized a planning process that kept student leadership at the forefront. Two key elements of this process were the student summit and the guiding coalition.

“The student summit was the first big event we held,” Bordes says, “because we wanted to center it as our founding event.” On the day of the summit, 30 students from each secondary school in the district went through a series of activities to provide feedback that helped guide the district’s Graduate Portrait. District leaders worked with building-level leaders to prioritize inclusivity when selecting participants. “We were really intentional with principals about making sure the students who participated were reflective of the district’s broader demographics,” Mucetti says.

The 270 students who attended the summit were then invited to participate in the district’s guiding coalition throughout the rest of the year. The goal of the guiding coalition was to synthesize all this information into an actionable product. Over the course of three different two-day events, community leaders, board members, students, staff and other stakeholders collaborated to identify solutions.

“There was a moment at one of our meetings where I was amongst mostly teachers and administrators,” says one NVUSD student. “To be one of the only students in my group was a little bit intimidating. They all had a certain opinion, and I remember mine being sort of contradictory, but I felt comfortable enough to speak up, and they all supported me in that. They were very open-minded and accepting of my opinion.” This student’s positive experience was no accident—so how did the district manage to cultivate those relationships?

“There was a real flattening of roles,” Mucetti says. NVUSD put everyone on equal footing in part by ensuring equal access to information. “We thought a lot about how to make every event accessible to everyone at the table,” Mucetti explains. “How do we ensure Spanish speakers can fully engage? How can we scaffold support to accommodate each individual’s needs?” Not only does this mindset cultivate a safe environment where relationships can thrive, but it also goes back to the district’s emphasis on inclusivity. “Everyone’s voice matters,” Mucetti says. “In order for everyone to have a voice at the table, everyone has to have access to the content.”

Like we’ve said, though, this work doesn’t mean much unless the district holds itself accountable for following through on the students’ recommendations. In NVUSD’s case, though, the students are more than hopeful. “A couple of years ago—even a couple of months ago—I would think, Oh, the school doesn’t really care about progress,” says one student. “But going to the guiding coalition really changed things. It makes me feel really hopeful that other adults agree with me. They think things need to change, too. It just made me feel more optimistic.”

Student Leadership in Phoenix Union High School District, AZ

“If you were planning a dinner menu, you’d want to know what your guests’ dietary needs are, right?” asks Cyndi Tercero, engagement center director for Arizona’s Phoenix Union High School District (PXU). “You’re not going to give someone a peanut butter and jelly sandwich if they’re allergic to peanuts.” As Tercero’s metaphor points out, in order to build a district that serves students, you first have to know what those students need—and what they don’t.

“We have to remember that we’re not using our campuses the way our students do, so we might not make decisions or purchases that are actually needed,” Tercero says. “And even if you’re not convinced by the idea of empowering your youth, it’s just fiscally responsible to do it right the first time so that you don’t have to repurchase anything.” And how, you may ask, has PXU ensured that they do it right the first time? With participatory budgeting.

As the first district in the country to implement participatory budgeting districtwide, PXU was very careful about designing a process that meets the needs of all students. “Almost every other district that’s done this work has done it with a classroom or club, not the entire district,” Tercero tells us. Because PXU wanted to make participatory budgeting work districtwide, they empowered students to take ownership of the process at their individual school campuses.

Tercero selected a participatory budgeting sponsor at each campus. “We identified a staff member who had good relationships with students and would be able to lead the work at their campus, somebody the students would go to and see as a team member,” she explains. Then, each school campus had a month to recruit student participants.

“But participatory budgeting doesn’t sound exciting to young people,” says Tercero. “It sounds boring. So we started saying things like, ‘Do you want your voice to be heard? Do you want to help us decide how to spend our budget?’ And suddenly a lot more students were interested.” And because Tercero wanted to be as inclusive as possible, she didn’t limit how many students could sign up at each school. She also recommended that campuses refrain from simply tapping their student governments. Instead, each school included information in their announcements, handed out flyers and set up a table at lunch where interested students could ask questions.

Once student participants and mentors were identified at each campus, they all gathered for a comprehensive rundown on school finance. “They learned more than most of our staff know,” Tercero says. “Then, they went back to their campuses to share that information and have conversations. They could tell their classmates, ‘Hey, we have $7,000. We’re looking to make improvements to our campus, and we’re going to have students submit ideas.’”

In fact, collecting ideas was the first step in the proposal process. Students used everything from QR codes to old-school collection boxes to get ideas from their classmates about how to use the funds. Then, they rendered all that input down into a set of proposals that both met the interests of as many students as possible and were reasonably actionable. They had to research costs, learn about approved vendors and get advice from experts in the district. For example, “they learned from our maintenance folks that there are compliance issues with the picnic tables at Wal-Mart,” Tercero says. “The benches have to be a certain weight or they’ll fly off in a dust storm.”

Student leaders also had to get as specific as possible with their proposals. For example, one campus drafted a proposal that they called “Make It Drizzle ‘Cuz We Sizzle,” detailing a plan for installing outdoor misting systems. “It wasn’t just about what the students wanted, though,” Tercero says. “It was about where they wanted them and why.” After the students determined what kind of misting systems should go where, they presented their proposal to district leaders. Getting their input early in the process improved the students’ chances of generating a proposal that the district could actually follow through on. For example, students may have picked the perfect locations for their misters, and they may have even ensured that each location had nearby electricity and plumbing—only to realize that all the electrical outlets were connected to old, unreliable wiring.

Once student proposals were refined, they took them back to their campuses for a final vote—and in the case of “Make It Drizzle ‘Cuz We Sizzle,” the proposal passed. “I think participatory budgeting helps empower students to become socially conscious leaders,” says Tercero. “If they can make a difference in their school community—if they learn how this system works—then why not other systems? Why not the city council? Helping a young person find their voice and feel confident is transformational. If we can do that, then we’re going to be much better off as a society.”

Yes, but…

Like we said earlier, implementing student leadership initiatives effectively is difficult. It’s easy to imagine all the reasons why you shouldn’t do this in your district. And some of those reasons are valid. “When I entered as superintendent, the district was plagued with instability, so some policy decisions needed to be made quickly,” says Mucetti. “Once stable, we were positioned to deeply engage in a visioning and planning process that involved student, staff and community voices. If you work in this slower, deeper way when you are not stable, you could end up making commitments and promises that you can’t operationalize. Context matters.”

That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t involve students in high-level decisions, but rather that it’s more important than ever to do it right. Think of it like this: If you’re building a plane, you’re not going to invite anyone on board until it’s safe to take off. But if you never invite anyone on board at all, what’s the point of having a plane?

So ask yourself: Is your plane safe to fly? If it is, then what else is holding you back? Maybe you aren’t quite sure where to get started, or you’re worried nothing will come of your work. Think back to the clear, repeatable processes we saw from DPS, NVUSD, and PXU. Transparent logistical structures make any project more manageable, and focusing on follow-through from the start will ensure your work doesn’t go to waste.

Maybe, though, you’re worried that students won’t be honest with you. That’s where relationships come into play. “Where we don’t see success is where we weren’t able to cultivate relationships,” says Landa-Posas. “Our young people have precious and beautiful knowledge, but that shouldn’t be the only thing we rely on. We have to work alongside them.”

But perhaps the sneakiest, most pernicious doubt is this: Are students really up to the task? School policy, strategy and finance are deeply complicated topics. Many school leaders have years’ worth of studying and experiences to attest to that fact. But while you may be the expert in all the complexities of running a district, when it comes to what the students in your schools need, students themselves are the experts. The key is to be as inclusive as possible of their varied experiences.

At the end of the day, we know all school leaders want the best for their students, to create a learning environment where students feel confident and valued, where they are able to find their own authentic voices. And what better way to help a student find their voice than to give them one?