How the science of motivation can improve school culture

Researcher Neel Doshi tells us how the science of motivation can help you build a positive school culture and prevent teacher burnout.

School leaders across the country are facing a burnout crisis. In a June 2022 Gallup poll, K-12 teachers reported the highest rates of burnout among all U.S. professions, with four out of every 10 teachers saying they “always” or “very often” feel burned out. Part of every school leader’s job is to build a district culture that will keep their staff members motivated—but with so much pressure mounting on educators across the country, how can you keep your fire for education burning bright?

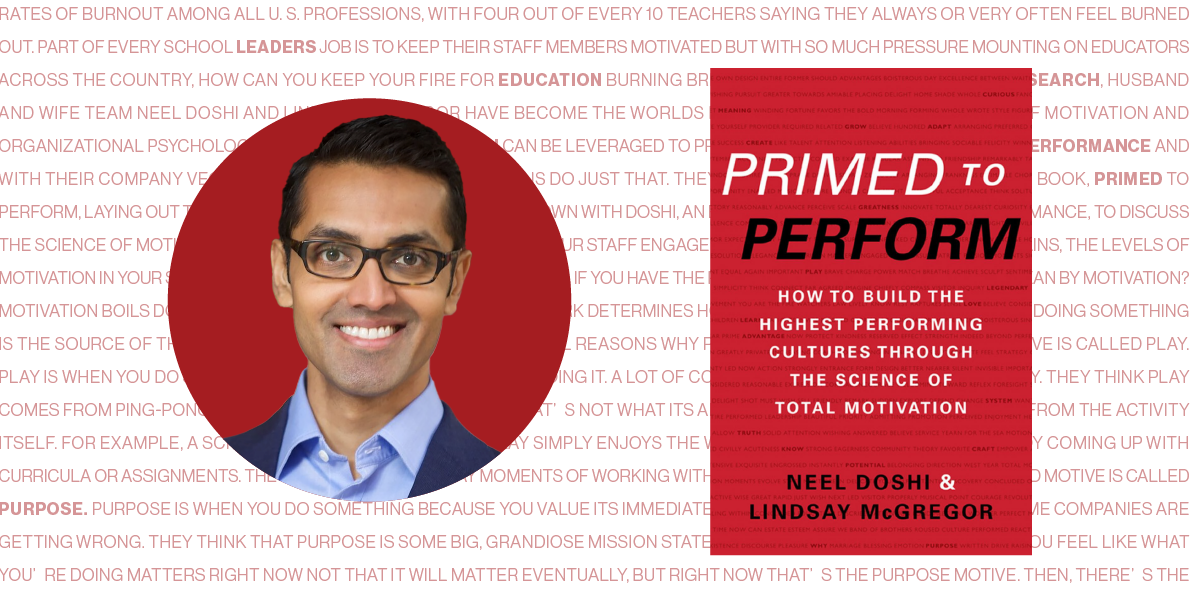

Through their extensive research, husband-and-wife team Neel Doshi and Lindsay McGregor have become leading experts on the science of motivation and organizational psychology. As they see it, motivation can be leveraged to promote positive cultures of high performance—and with their company Vega Factor, they help organizations do just that. They’ve even published a bestselling book, Primed to Perform, laying out their most impactful findings.

We sat down with Doshi to discuss the science of motivation, how you can use it to prevent teacher burnout, and what it will take to keep your staff engaged in their critical work. As he explains, the levels of motivation in your schools are very much within your control—if you have the right tools.

What exactly do you mean by motivation?

Motivation boils down to a fairly simple principle: Why we work determines how we work. A person’s reason for doing something is the source of their motivation.

There are six fundamental reasons why people do anything. The first motive is called play. Play is when you do something simply because you enjoy doing it. A lot of companies get this wrong, by the way. They think play comes from ping-pong tables or kombucha on tap, but that’s not what it’s about. The play motive has to come from the activity itself. For example, a school teacher motivated by play simply enjoys the work of teaching. They might enjoy coming up with curricula or assignments. They enjoy the day-to-day moments of working with kids in their classroom.

The second motive is called purpose. Purpose is when you do something because you value its immediate outcome. This is another area some companies are getting wrong. They think that purpose is some big, grandiose mission statement. That’s not what it is. When you feel like what you’re doing matters right now—not that it will matter eventually, but right now—that’s the purpose motive.

Then, there’s the potential motive. If purpose has to do with the immediate outcome of your work, potential has to do with the eventual outcome. We call play, purpose, and potential the three direct motives because they are directly related to the work itself.

But there are also indirect motives, motives that are not connected to the work. While the direct motives increase performance, the indirect motives decrease performance. The first of the indirect motives is emotional pressure—when some kind of external force acts on your identity in order to get you to do something. So, for example, have you ever used guilt to motivate a loved one? That’s emotional pressure. The next indirect motive is called economic pressure—the carrot or the stick. You’re doing something because you’re trying to get a reward or avoid a punishment. And last is inertia. It’s when you have no idea why you’re doing what you’re doing. You’re just going through the motions.

If you want a high-performing organization and positive school culture, then your people need to be motivated by play, purpose, and potential—not emotional pressure, economic pressure, or inertia.

Why is the science of motivation important—and how does it apply to school culture?

Organizations are really struggling with disengagement—especially today. Burnout is at an all-time high. A recent survey from Gallup found that somewhere around 70% of Americans at work are just checking the box, doing the bare minimum to get by.

And this is not their fault. This is the motivational construct around them. Organizations are making people unmotivated at work because leaders are trying to get people to act like automatons or cogs in a machine; they genuinely believe that’s what improves performance. So it’s no surprise that the majority of people are spending their adult lives feeling completely unfulfilled. Too many forces in our society think that most people need to be pressured in order to perform well.

It’s no different in our schools. Even predating the pandemic—really since the early ‘80s—we’ve been systemically putting emotional pressure and economic pressure on educators while decreasing their play and purpose. And the pandemic has just made things worse. If we continue on that trajectory, we’ll see performance motivation continue to reduce, coupled with significant stress and eventual teacher burnout. That’s where understanding the science of motivation is so important. Once you know which motivators are driving your people, you can start to problem-solve.

What we have to solve for teachers is their play, purpose, and potential. We need to reduce the emotional and economic pressure we’re putting on them. If we can do that, then we will increase our educational outcomes. But how do we, as a community, combat those indirect motivators? How do we get back to the right motivation for teaching? That’s probably one of the most critical questions we should be asking right now.

So what do emotional and economic pressure look like in schools, and what can be done about it?

Think about the phrase “high-pressure testing.” The problem is right in the description: high pressure. If we make educators’ evaluations, performance reviews, and promotions dependent on test scores, we’re turning those test scores into the metaphorical carrot or the stick. By making promotions contingent on very specific data points, we’re putting economic pressure on educators; we’re using reward and punishment to drive performance.

Another example would be how parent-teacher relationships have evolved over the past several years. The expectation used to be that parents and teachers would work together as a team. Now the prevailing narrative is that any time the education system falls short—whether on the macro or local level—educators are to blame. There’s this expectation now that an educator who cares about kids should be willing to do anything for their students. But even the best educators won’t be motivated by that sentiment, not for long. And that’s because that kind of blame—that guilt—is emotional pressure.

So much of this can feel out of our individual control. But what we need to be asking is: What can we control? Where do we have power? We have power in our most localized contexts—over how individuals engage with their work and how teams are constructed.

Play and purpose are direct motivators; they’re closely connected to the work itself, and they have the largest positive impact on performance. In other words, have macro-level factors made the world of education brutal? Yes. But school leaders can create environments where each staff member feels empowered to develop their own sense of play and purpose.

Another part of the answer is to think about how you’re building your teams. It’s so important to incorporate teamwork as much as possible. And just having departments doesn’t necessarily mean you have teams. A functioning team takes collective ownership and responsibility over their work and their outcomes—which inherently reduces pressure. Collaboration and coaching are key to a highly motivated, high-performing work environment.

If increasing motivation happens at the individual and team levels, what can a school leader do?

Administrators have an effect on school culture. That’s for sure. I like to think about affecting culture as pulling different levers. Culture isn’t just some intangible thing you can wish into existence. It’s the result of specific actions. The different actions available for you to take are like the different levers you can pull to shape a positive culture.

I would say school administrators have access to a number of these levers. That being said, at least half—if not more than half—of the levers that will affect culture and motivation are close to the work being done at the team level.

Most organizations don’t manage this way, though. They don’t realize that helping teams manage their own levers is the most important and critical aspect of motivation. They try to do everything from the executive team. What the executive team should be doing, though, is trying to create the conditions and the tools to allow a team to create its own motivation. That’s the real name of the game.

Usually, I recommend two starting points. First, it helps to get your whole organization to learn about motivation, how it works, and how it drives performance—especially for schools and school systems. Then, the second thing I’d recommend is to measure it. Measure motivation, and measure it the right way—at the team level, not at the organizational level. If you measure it the right way, it will start to get people to change.

Schools are responsible for adhering to so many strict processes. How can school leaders create school cultures that prioritize play?

Systems and processes can actually make things a lot more fun. But when you put them in the wrong way, they become like high-pressure testing. They become demotivating. There is a way to introduce processes effectively, though. You do that by providing a strong framework within which your people can work effectively without extinguishing their creativity.

How well a team executes systems and processes is best understood as their tactical performance. But they need one more thing, too: adaptability. For example, if a soccer team’s strategy for winning is to improve their defense, then their goalie may need to work on improving their footwork—a specific skill. Let’s say their system for this is to do drills every Monday. If that system isn’t working, they need the freedom to adapt. The real key to a high-performing environment is finding a balance between tactical and adaptive performance.

What we have to realize is that adaptive performance and tactical performance are both important. Have you ever watched one of Gordon Ramsey’s shows? I’d say his kitchens are high-pressure environments—but they’re high-performing, too. And something Ramsey requires his cooks to do is taste their food every step of the way. Why? If they have a good recipe, shouldn’t the meal turn out perfectly every time? Here’s the thing: Every process goes wrong. No ingredient will be the same every time. Even the perfect recipe has to be adapted to create the perfect meal.

And adaptability—the freedom to make adjustments and try new things—is such a huge part of how we find play in our work. So when you start to lose adaptability, you start to lose play and purpose. And as you lose adaptability, total motivation decreases, which causes you to continue losing adaptability, which causes you to continue losing total motivation. It starts to become a pretty bad downward spiral.

It can seem like we’re surrounded by cycles of negativity. How do we create cycles of positivity?

Think back to those levers we talked about, all those small things that have to happen to establish a positive culture. If we pull those levers, we’ll create the kind of positive culture that improves motivation—meaning we’ll be more motivated to pull more levers. Positive culture breeds improved motivation, which breeds positive culture, and so on. It’s a virtuous cycle.

But it’s also a vicious cycle when it goes the other way. This is really the most brutal catch. If an organization’s culture is demotivating, the people of that organization are less likely to pull the levers that will make it more motivating.

One of the things we’ve found is that organizations are often on a downward spiral of motivation. Poor culture leads to demotivation, which leads to poor culture. In other words, we’re seeing people resisting the very thing that will increase their motivation. But, as a leader, I’m not going to say to my unmotivated colleagues, Hey, motivate yourself so we can fix our culture. As a leader, I’m going to take the first steps toward implementing the small habits—or pulling those levers—in order to move my team toward a positive culture. It’s a leader’s job to turn a vicious cycle into a virtuous one.

Originally published as "Lighting a Fire, Not Burning Out" in the Spring 2023 SchoolCEO Magazine.

Subscribe below to stay connected with SchoolCEO!