Dr. Yann W. Lussiez: Hale, Hūlō and Healing

Guest writer Dr. Yann Lussiez explores how culturally responsive leadership can guide schools through hardship and foster connection.

In August 2023, the Lahaina fires devastated our school community on the island of Maui. Everyone was affected in some way—many experiencing the tragedy deeply through the loss of loved ones, property, employment or housing. Our school’s senior leadership team responded as we had during the pandemic, assessing the situation and creating communication and reopening plans. But this crisis was different, affecting our community in a more profound way. This fire wasn’t just another natural disaster. It exposed deep historical trauma, generations of environmental degradation, and the loss of native land, language and culture to colonization, greed and racism.

This was the beginning of my fourth year as lower division head at Kamehameha Schools Maui, an independent school for indigenous Hawaiian children. I am neither Hawaiian nor indigenous to America. My story begins in Lille, the north of France, where I was born, and it continues in Colorado, where I received the majority of my formal education. Like most immigrants, I grew up straddling two cultures and languages. My journey as an educator began with my Peace Corps service in the Central African Republic. It later threaded through public and private schools as a teacher and administrator in New Mexico, Venezuela and Turkey.

These experiences in diverse settings, coupled with my doctoral work in empathy and school leadership, instilled in me the belief that “all children laugh in the same language” and that a sense of joy, empathy and compassion needs to be the foundation of school leadership. Plainly put, we are here to build good people. As a scholar-practitioner, I have come to embrace a culturally responsive leadership framework as the best approach to meeting the school community’s needs.

Culturally Responsive School Leadership

What I appreciate about culturally responsive leadership compared to other leadership models is the focus on acknowledging, respecting and incorporating all our students’ and faculty’s backgrounds and identities into the school’s culture. We begin this work by building self-awareness of our own cultural values, where these values came from and how they were formed. Through cultural humility, we then seek to understand the values of our school community, acknowledging that these values may be different from our own. We must then be committed to continuously seeking cultural knowledge, especially with a focus on making our schools more inclusive.

Through self-reflection, empathy and compassion, we not only understand and acknowledge our community’s priorities but also foster a shared commitment to the change process, where both leaders and the community take joint responsibility for shaping the future of the school. Importantly, this relationship goes both ways. While we get to know the community, they also need to know us—not just as leaders, but as individuals who are open to learning.

As the reality of the Lahaina tragedy became clearer, our leadership team was deeply aware that our school community was looking to us to provide a sense of safety, to show that we had a plan to take care of our students. Culturally responsive leadership requires us to go further than traditional leadership models; it asks that we actively work to heal and respond to historical trauma, to understand how this history can complicate or impact a crisis. After all, a crisis is the ultimate test of an organization’s core values, of its leadership. And at the end of the day, families want to see their communities supported and honored at all times.

Embedding Cultural Knowledge

The emotions were heavy on that first day back with students and faculty in the gymnasium. Our kahu, or spiritual leader, brought us together through prayer and song, joined by our kumu, or teachers. Culturally responsive leadership understands that ritual, prayer, music and song are foundations of connection and healing.

Our head of school then welcomed everyone back, sharing his thoughts and highlighting the support mechanisms we had put in place. He embodied culturally responsive leadership by acknowledging the deep emotions felt by our community, offering words of solidarity and emphasizing that our collective strength would guide us through the healing process. But through it all, one symbol of hope stood out: our hale.

As part of our Hawaiian culture-based education framework, our fourth and fifth graders had built a hale—a traditional home or structure made from natural materials such as wood, grass and thatch. This project, spearheaded by two kumu with deep commitment and knowledge of Hawaiian culture and ancestral hale building, connected students with their kūpuna, or ancestors, by teaching them stories and traditional building methods.

The hale, later named Kūhāluapou, soon became the students’ passion project. They worked on it before school or over recess, practicing tying special knots over and over. They also dove into deep discussions on the proper location for building, correct cultural protocols and their intentions when working on the hale. After its completion, our kumu shared student reflections on the process and what they learned with the executive and senior leadership teams. As we listened to our students share how the project connected them to the land, their people and their kūpuna, there wasn’t a single dry eye in the room. Their voices highlighted the essence of what culture-based education and culturally responsive leadership is all about—rooting our students in their identities and supporting them in being seen.

As leaders, we must recognize that culture shapes all aspects of human experience and actions. It influences our mindset, feelings, behaviors and how we relate to one another. Culture is the lens through which we view and interpret the world. Quite simply, I know I am a better leader when I embrace culturally responsive leadership and indigenous ways of knowing. Ignoring or avoiding culturally significant opportunities signals that our community’s cultural identity lacks value or relevance. It suggests to parents that we are not fully accepting, open to personal growth or willing to confront our own limitations and discomfort. Leading with humility is essential to fostering genuine connections.

Amid the fierce winds that fueled fires in both Lahaina and Kula, on the western slopes of Haleakalā near our school—uprooting trees and toppling power poles—the hale stood strong: untouched, unchanged and truly a symbol of resilience amid destruction. Recognizing that a sense of place is integral to Hawaiian culture, I emphasized to our community those first days back that the hale was more than just a culture-based, hands-on assignment. It stood as a testament to the strength of ancestral wisdom and a reminder of what we could achieve together as a community. For many, the hale’s strength was evidence that we weren’t alone; the kūpuna were with us. Culturally responsive leadership takes cultural knowledge like this into account, opening the window to compassion and empathy while taking purposeful actions to support and empower those we lead.

Compassion at the Core

Compassion is at the heart of culturally responsive leadership. As leaders, we need to see our students as complex, diverse and, in some cases, wounded individuals in need of healing. In times of emotional strain, compassion calls for creative and innovative ways to bring people together and lift spirits.

I have always embraced the use of humor and playfulness in leadership. I’ve been known to dress up as one of my “cousins”—Butch, Opera Man or Chef Pierre—to sing “Happy Birthday,” tell a funny story during our school broadcasts or share jokes with students during lunch. The students at Kamehameha particularly liked “Auntie Gertrude,” an elderly British woman who goes on and on about the importance of tea and the historical relationship between Hawaii and Britain. In particular, Auntie Gertrude likes to highlight that this early friendship between the two resulted in the Union Jack being incorporated into the Hawaiian flag. Maybe Auntie Gertrude was so popular because students loved seeing me in a dress and gray wig.

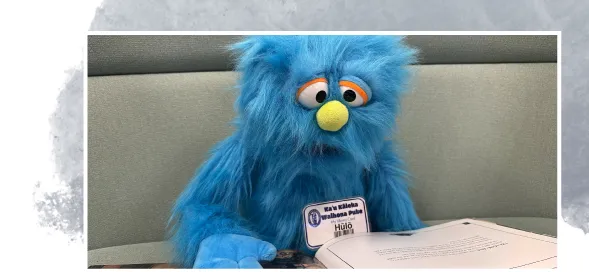

As the weeks progressed and we began to return to our daily routines, I realized our students and staff were emotionally drained. We needed something new to unify us. Students needed uplifting imagery and voices to contrast the tragedy of the island, which inspired me to introduce a new character: a bright blue ventriloquist puppet. He made his debut during our schoolwide morning broadcast “Wake Up Warriors,” run by our fifth graders.

In his first episode, the puppet interrupts me at my desk, and we soon discover he doesn’t have a name. The puppet learns that in Hawaiian tradition, names are given with deep meaning—often passed down through generations or inspired by dreams, ancestral wisdom or significant events—and that these names often highlight personal characteristics or one’s lifelong responsibilities. The students submitted suggestions, voted on a name and selected Hūlō, which is an expression of joy, like “yay!” or “hooray!”

In the weekly episodes that followed, Hūlō learned lessons like the importance of reading, where to seek help when sad, the proper behavior on the bus, safety on the playground and how to check out library books. What was especially inspiring was not only how quickly the students embraced Hūlō, but how the kumu also jumped in to be interviewed, share insights or teach life lessons. While the original intent was simply to bring joy to the school, Hūlō soon developed into a more culturally sensitive character. The students began creating their own episodes—teaching Hūlō how to count in the Hawaiian language ‘Ōlelo, telling jokes, sharing student stories written in ‘Ōlelo or showcasing their art focused on local wildlife.

These videos became concrete evidence of student engagement, honoring their ideas, culture and interests. By blending humor and compassion, we helped students process their emotions while giving them a voice in shaping Hūlō’s journey. This collaborative storytelling aligns with the Hawaiian tradition of passing on wisdom, underscoring that culturally responsive leadership is indeed a two-way street—where both leaders and the school community contribute to a shared narrative.

Building Relationships and Trust

The spontaneity of Hūlō’s segments required minimal planning, especially when the students took the lead in writing the episodes. Using just an iPhone, quick edits and a simple upload to a private YouTube channel, we brought joy to the school community. Hūlō provided me with a unique platform to build positive relationships with the students, empowering them and bringing relevancy. Hūlō was theirs. Students often came to my office so he would “wake up” and give them a hug. They would sometimes lose themselves in conversations with Hūlō, forgetting they were talking to a puppet. These interactions helped break down barriers, allowing students to address difficult issues or complicated feelings.

Traditional Western school structures are hierarchical, where the adults hold great authority over students. This limits opportunities for student voice and can lead to feelings of disconnection or alienation. As culturally responsive school leaders, we need to create a school culture that places value on collaboration and mutual respect.

Hūlō’s playful yet sincere interactions helped break down these traditional barriers between leaders and the community, creating connection and trust in a fun, approachable way. He became a symbol of comfort and familiarity during trying times, allowing students to feel heard and included. Students often told me they watched the episodes over and over with their families. On a few occasions, parents asked me to send special video messages or birthday greetings from Hūlō for their children. By the end of the year, Hūlō had his own dedicated yearbook page, a testament to the connections that had been built.

Puppetry may not be a traditional leadership tool, but it was exactly what our community needed at that moment. Drawing on my passion for theater, I utilized puppetry as a way to highlight that our school wasn’t all about academic rigor; it was also a place where culture and well-being were prioritized. Hūlō evolved into more than just a weekly puppet show; he became a bridge between me, the students and their families. This experience underscored the importance of self-awareness and community awareness in leadership, demonstrating how such strengths can bring joy to our schools.

Culturally Responsive Communication

Culturally responsive leadership can be as intricate as building a hale or as simple as introducing a ventriloquist puppet. As culturally responsive school leaders, whether in Hawaii or anywhere else, we are tasked with approaching our work with humility, openness and an eagerness to grow—as well as a commitment to learn about, embrace, legitimize and uplift the diverse values and traditions of our community. As part of this work, we recognize the importance of strategically embracing these cultures’ traditions in our school communications.

For example, in Hawaiian culture, elders are revered. We embraced this by launching Lā Kūpuna, or “Grandparents’ Day”—in which grandparents were invited to school for breakfast, lots of coffee, performances and quality time with their grandchildren. This was wildly successful, with over 400 grandparents coming to campus—some even flying in from neighboring islands.

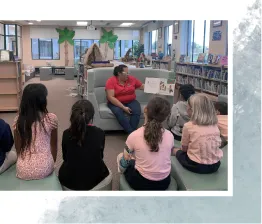

We also launched Wā Mo’olelo, or “Story Time.” Twice a month campus administrators, high school students, parents or community members were invited to come share personal stories rooted in Hawaiian culture or read their favorite children’s books. This was especially powerful when our local firefighters came to share, providing an opportunity for faculty and students to express their immense gratitude for their service during the Kula and Lahaina fires.

Embracing the principles of culturally responsive leadership—and, in this story, Hawaiian culture—has profoundly transformed me as both a leader and a person. This journey of discovery, connection and growth requires the courage to self-reflect and honor the cultural values of families in our schools. When families see their traditions embraced—through initiatives like building a hale or honoring kūpuna—they feel reassured that their children are in a safe environment that nurtures their identities, especially during times of loss and uncertainty. Ultimately, I have come to understand that culturally responsive leadership goes beyond managing logistics or ensuring academic progress; it’s about embedding the community’s values into the DNA of the school.

Becoming a Culturally Responsive School Leader

- Assess how your own cultural beliefs and biases influence your decision-making and interactions with your stakeholders.

- Take the time to learn about the values, histories and needs of the cultures in your school community.

- Evaluate your organization’s cultural responsiveness through surveys, focus groups or community meetings.

- Involve students, families and community members in decision-making processes to ensure diverse voices shape school policies and programs.

- Provide opportunities to allow students and families to share and celebrate their heritage and histories, like Wā Moʻolelo and Lā Kūpuna.

- Create platforms where students can lead initiatives, voice their concerns and propose culturally relevant projects.

- Foster spaces where students can physically engage with the environment, like a hale, community garden or other dedicated space.

- Make cultural responsiveness an ongoing journey for you and your employees by regularly reflecting on and adjusting practices based on feedback and new cultural insights.

Dr. Yann W. Lussiez is an assistant professor in the Teacher Education, Educational Leadership Program at the University of New Mexico. He can be reached by email at ylussiez@unm.edu.