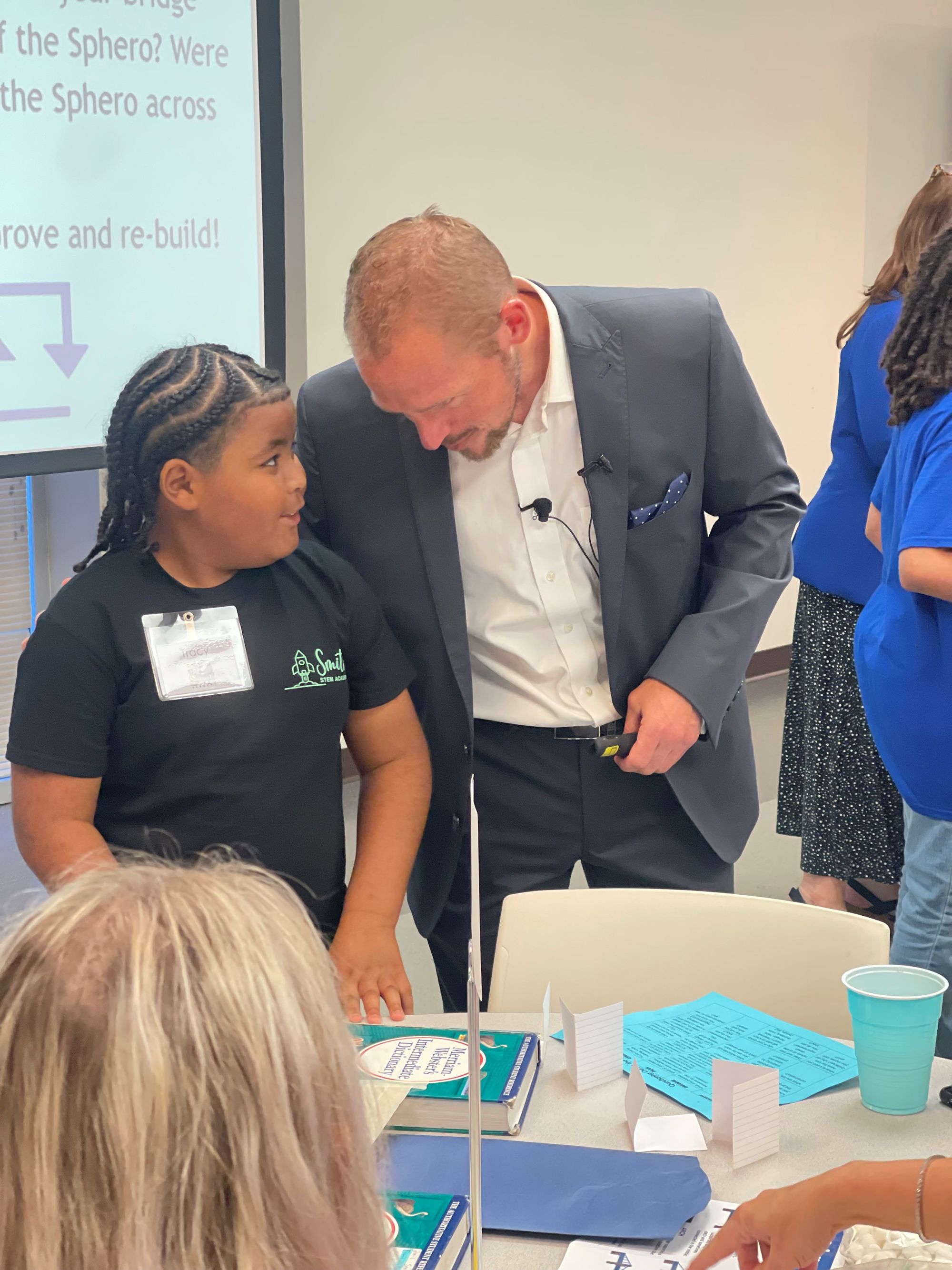

Dr. Quintin Shepherd's Relentless Compassion

How one Texas superintendent prioritizes people and refuses to give up on kids

When Dr. Quintin Shepherd entered his first superintendency, he was 27 years old. But just 10 years earlier, as a teenager on a farm in rural Illinois, he’d nearly left school altogether.

It was the 1980s, and Shepherd’s family was caught up in the chaos of the Farming Crisis—the worst economic crisis in agriculture since the Great Depression. “Everybody in the Midwest was losing their farms,” Shepherd tells SchoolCEO. “Our family struggled like any other farm family.” In the midst of this hardship, his family suffered an even more crushing blow: Shepherd’s father was in a major car accident. “Somebody pulled out in front of him on a country road. Dad never even touched the brakes,” Shepherd says. “There was a chance that we were going to lose him.”

The accident left Shepherd, a junior in high school, with a heavy weight on his shoulders. It was autumn, and the livestock needed tending to before the long winter months. “That meant the burden of responsibility fell to me,” he says. “I had to step up.” For a while, Shepherd tried to do both—go to school and keep his family afloat. But “trying to live two lives was impossible,” he says. “And family was the priority.”

That time running the farm could have determined the rest of Shepherd’s life—had it not been for the support of his teachers. One in particular stands out in his memory: an educator named Fred McLaughlin. “Every time he saw me, he was relentless about not giving up, not quitting,” Shepherd says. But McLaughlin and his colleagues did more than just encourage Shepherd; they helped.

“I’ll never forget when Fred McLaughlin showed up at our house, unexpected, with a trunk full of groceries the teachers had collected for us,” Shepherd says. “They knew us. They knew our situation and what we needed.” McLaughlin brought school books, too, “but those were secondary,” Shepherd tells us. “Like any good teacher, he recognized that basic human needs are most important.”

Shepherd’s father went on to recover, and Shepherd did graduate from high school. But those experiences on the family farm would continue to shape his philosophy of leadership even decades later. “I know what it feels like to not know when your next meal is coming,” he says. “After that, you lead differently.”

On the Way Up

Shepherd’s path to the superintendency was lined with mentors, people who believed in him more than he believed in himself. First was Dr. Elizabeth Wehrman, a music professor at Western Illinois University. “I actually started college as a pre-med student, but I really had no interest whatsoever in entering the medical profession,” he explains. “I took music classes because I love music.” Wehrman piqued his interest in music education, and he earned his teaching license in his final year of college. “She’s the reason I became a teacher,” he says.

After graduating, Shepherd taught music to grades pre-K through 12 while earning his principal credentials. After about five years, he applied to exactly one principalship, at an elementary school in Amboy, Illinois. He didn’t really expect it to pan out. “I thought, Maybe they’ll give me an interview, and if nothing else, at least I’ll practice interviewing,” he says.

The interview went well, and afterward, the school board president walked him out. “He said, Look, typically the people we get here are either on their way up or on their way out,” Shepherd recalls. “I see you as somebody on their way up.” Not long after, Shepherd got the call. He’d gotten the job.

Amboy was small, with fewer than 1,000 students across three schools. Shepherd spent one year as the elementary principal, moving to the high school the following year. About five months into that job, he was pulled into the superintendent’s office. The board president was there—the same one who had hired him two years before. “I just figured I was going to get fired,” he says, laughing. Instead, they asked him to be the district’s next superintendent.

Shepherd was shocked, to say the least. “I was like, I’ve been a principal for less than two years, and they’re wanting to give me the keys to the district?” he says. “But they had an unshakeable confidence in me—probably more than I had in myself.” Shepherd refused at first, but they kept asking. Finally, he applied and got the job. He became Amboy’s superintendent at 27 years old.

After four years at the helm, Shepherd left Amboy better than he’d found it. “The district had started to stumble academically and financially,” he explains. “But because I knew the people and built on those relationships, we were able to make some pretty significant changes.” Academics improved, and the district earned the Illinois State Board of Education’s highest rating for financial health.

But “in Illinois, the story they tell you as a superintendent is that if you’re any good, you’ll get recruited up to the Chicagoland area,” he says. “That’s where all the action is.” And that’s exactly what happened to Shepherd. An executive recruiter pointed him in the direction of Skokie School District 69, a suburban system northwest of Chicago.

At the time, Skokie 69 was struggling. “They were in all kinds of financial turmoil, and their student achievement scores were tanking,” Shepherd says. Over the previous decade or so, the community’s demographics had drastically changed, but the district hadn’t changed with them. While the population had once been homogenous, the area had since become a major center for refugees, creating a boom of cultural diversity. “There were 115 languages spoken,” Shepherd explains—but the district’s ELL programming hadn’t kept up with this shift. The community’s economic makeup had also shifted; “there was tremendous poverty,” Shepherd says, “but they were still operating as though it was a wealthy district.” The superintendency at Skokie would not be an easy one. But Shepherd was, as he puts it, “up to the challenge.”

Compassionate Leadership

During Shepherd’s five years there, Skokie 69 flourished. The district’s restructuring of its ELL program garnered recognition from both the Illinois Association of School Administrators and the state board of education. Further restructuring, along with grants, improved the district’s financial standing by several million dollars.

It was during his time at Skokie that Shepherd realized he wanted to be a different kind of leader. “When you first start in this job, you play by the rules as they are handed to you,” he says. “I was doing leadership the way I was taught to do it, the way I had seen other people do it—but it was like a suit that didn’t quite fit.”

As Shepherd sees it, traditional leadership focuses on competence. “Competence is transactional leadership,” he says. ”If I’m judging you on your competence, then it’s a transactional relationship. I’m thinking about what you can do for me.” But increasingly, Shepherd found himself less interested in competence and more interested in compassion.

If you take it back to its Latin roots, “compassion” most literally means “to suffer with”—and Shepherd has taken that definition to heart. “A compassionate conversation is one where we suffer together,” he says. “You share how you’re suffering in your world right now, and I’ll share how I’m suffering in mine. We can connect over our suffering.”

This idea transformed the way Shepherd led in Skokie. “We were the first district in the state of Illinois to move away from a traditional salary schedule, and we did it with union support,” he explains. “The reason why was that for the first time, I went to the union and shared my suffering—and I asked them to share their suffering.” Shepherd opened up about the difficulty of being constrained by limited state funding and local taxes, about how much he hated cutting programs and letting people go. The district’s teachers, in turn, were frustrated at not knowing what they were going to be paid the next year—and felt that their experience and education weren’t being valued.

Together, they made the decision to move away from a traditional salary schedule with a set pay matrix. Instead, raises would be based on a percentage of a teacher’s current income and level of educational attainment. The new model would also allow Skokie to negotiate raises after state funding was set, giving them the flexibility to lower raises in tight financial years. With this wiggle room, they could avoid layoffs and program cuts. “We didn’t get there through force of will, hierarchies, or power,” Shepherd says. “It was just sitting down with the union and saying, This is hard for all of us, and we’d like to make it better. We connected around that suffering.”

“That became a hallmark of my leadership,” Shepherd tells us. “I will suffer with the community, I will suffer with a student, I will suffer with a family—and I’ll ask that they suffer with me. As a superintendent, I have these amazingly complex problems that I don’t have the foggiest idea how to solve: when to run a bond, when to open a school, how to make an ELL program more effective. So I made a commitment as a leader. Anytime I’m faced with a complex issue, before I try to come up with my own solution, I go to the community and share my suffering. It’s amazing to me how many people jump forward to help.”

What I Want For You

After five years in Skokie, Shepherd made the leap across state lines to lead Iowa’s Linn-Mar Community Schools. He stayed there three years before an executive recruiter approached him yet again, asking him to check out Victoria ISD (VISD) in Texas. As had been the case at Amboy, it was the school board members who made the strongest impression on him.

“One of the most interesting things in education, to me, is the school board,” Shepherd tells us. “Who are these people? How do they work together? Are they willing to trust a superintendent who leads a little bit differently? Are they courageous? Are they vulnerable?” What he saw in VISD’s board impressed him. “I knew they were interviewing me, but I interviewed the hell out of them, too,” he says. “And the more questions I threw at them, the more I started to like them.”

A key question Shepherd had in mind related to that dichotomy of competence versus compassion. “I had already decided that at my next job, I wasn’t going to tell people what I wanted from them—I was going to tell them what I wanted for them,” he explains. “What I want from you is all about your competence. It’s transactional. But what I want for you, again, speaks to that compassion, suffering together. I want compassionate relationships with the people I work with.”

So in his first interview, he invited VISD’s board members to have that conversation. And they did. “They were super uncomfortable at first, but they really opened up and shared some beautiful things—things like, We want for you and your family to feel like an integral part of our community,” Shepherd explains. “They focused on me as a human being, and that made me want to do the best work of my life.”

Now, Shepherd has been at VISD for five years—and though there’s been some turnover in membership, he still has those compassionate relationships with his board. “It’s a love fest,” he tells us, laughing. Maintaining those relationships over time, of course, requires “a relentless focus on communication,” he says. He points to the words of George Bernard Shaw: The single biggest problem in communication is the illusion that it has taken place. “Better to over-communicate than under-communicate,” he says.

But that close-knit board culture stems in part from a mutual effort to understand one another, right from the get-go. “You don’t run for the school board without having an agenda, so share that with me,” he says. “Share what you don’t like about the district or what you want to change, and I’ll share the struggles that we’re dealing with and the great things that are happening. That’s how we connect and get closer.”

The Best Work of His Life

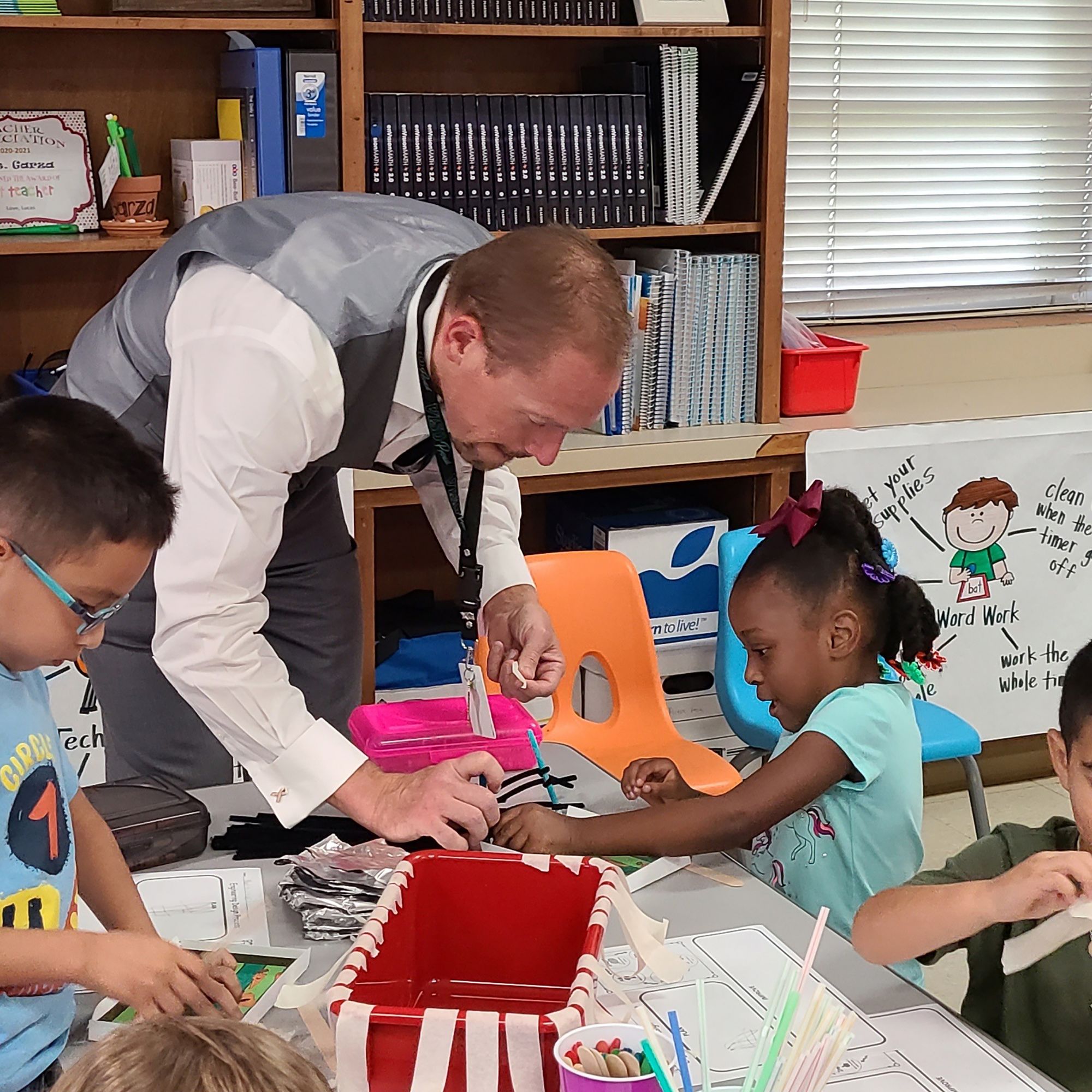

Multiple times over the course of our conversation, Shepherd referred to his work at VISD as the best work of his life. Much of that work centers on caring for students as people—on sharing and understanding their suffering, then working to alleviate it. “We have made such amazing leaps and bounds in terms of student well-being and student achievement, especially for kids who have typically been underserved,” he says. “Pre-pandemic to post-pandemic, we increased the percentage of kids who are taking dual credit and AP coursework significantly—and their achievement scores went up at the same time.”

Given his history, it’s no surprise that Shepherd is particularly passionate about students at risk of dropping out. “When you take students who are in credit recovery, there’s a group of kids who can’t do well and a group of kids who won’t,” he says. “The kids who won’t are self-sabotaging, and they need a different kind of support. But for kids who legitimately can’t, who have honest-to-God barriers in their lives—what if we put every effort we can imagine into removing all of those barriers?”

That’s exactly what the district does for credit recovery students at its VISD Success Academy, a partnership with nearby Victoria College. Students in the program attend classes on the college’s campus in VISD’s six rented classrooms. “Some of these kids have zero credits through high school. They’ve historically struggled with discipline or attendance issues,” Shepherd says. For many of these students—much like Shepherd in his high school years—life has gotten in the way of education. Some felt it necessary to leave school to support their families. Others have struggled with mental health or other medical concerns.

The Success Academy aims to take care of those life concerns for students, allowing them to refocus their attention and energy on school. “This is the deal of a lifetime,” says Shepherd. “Our students get emotional support, academic support, coaching. We even cover their food costs. Our goal is to enroll as many of them as possible in college by the time they’re done.”

At the partnership’s inception in 2021, VISD placed 120 kids on Victoria College’s campus. By the end of the year, all 120 were enrolled in college. “It’s the whole person approach,” Shepherd says. “It’s looking at these kids and saying, We love you, and we’re not going to give up. We’re going to find a way to make this work.”

It’s not hard to see where Shepherd got this mentality. It started when he was a junior in high school, when a teacher brought him a trunk full of groceries and a bag of books. “You just don’t give up on kids, ever,” he says. After all, no one gave up on him.