Dr. Hank Thiele: From Scout to Super

In the Scouts, Dr. Hank Thiele learned to solve problems on the fly—and he hopes to instill the same skill in his students.

From Scout to Super

How Dr. Hank Thiele learned to figure things out as he went

If you look at the curriculum guide for Community High School District 99 in suburban Chicago, you’ll notice it looks a lot more like a college course guide. The first two years of high school, students in Downers Grove, Illinois, are expected to take traditional core courses like math and science. But in their junior and senior years, they have a large variety of subjects to choose from, giving them the opportunity to dig into the areas they’re interested in—just like college. The goal is to give them more ownership of their education while also preparing them for the next stage of their lives, explains Superintendent Dr. Hank Thiele, a 30-year veteran of K-12 education. It’s the kind of experience Thiele wishes he had received when he was in high school.

“Nobody was talking about the why. Nobody was asking what we wanted to do after high school,” says Thiele of his own experience. Instead, students were expected to graduate because, well, they were supposed to. As Thiele tells it, that disconnect between his classes and his interests affected his performance. He was engaged in the subjects that interested him but “barely compliant” in the subjects that did not. “I was not a very good student at all,” he admits. “I wasn’t able to really tailor my learning to the things that I was passionate about. I was just working toward one thing at the end.”

Be Prepared

So how did a “bad student” with middling grades end up in the education field? A Scout since he was a young boy, Thiele took a leadership role in his Eagle Scout troop during high school. Every week, he would perform the role of teacher—creating a meeting agenda and designing a lesson plan for his fellow Scouts. As a result, he started paying more attention to his teachers’ lesson plans at school—and thinking a lot about how he would do things differently if he were in charge.

He didn’t know it at the time, but he later realized the Scouts follow a competency-based microcredential system. “The whole badging system of Scouting is advancement-oriented. You advance in degrees based on your skills,” Thiele says. And he appreciated that Scouts had a choice about what lessons they learn. “You can become an expert in certain areas that interest you and then build your overall credential by doing those things,” he says. “It was so different from school.”

While Thiele felt high school did little to prepare him for the real world, there’s a reason the Boy Scouts of America’s motto is “Be Prepared.” Scouts taught him to figure things out as he went, gaining independence and resourcefulness in the process. “It’s stuff that you could definitely see yourself using. You’d learn something during the week that you would use that weekend on a camping trip,” says Thiele. What’s more, Scout leaders regularly checked in to see how Thiele was doing and to offer individual support.

Although Thiele was taking note of his instructors’ teaching styles at school, he didn’t consider education as a career until one fateful night at a regional Scouts meeting. “There were a hundred kids in the room. I built the whole lesson, and I ran the whole thing,” he tells us. “At the end some guy came up to me and told me he was an educator. He said, ‘A lot of people in my field can’t put together a lesson plan as tight as you did tonight. You should really think about going into education.’” Thiele did think about it—and decided he agreed.

Harmonizing Teaching Styles

Two of the subjects that actually engaged Thiele in high school were science and band, so he went on to study science and music education in college. After he graduated, he landed his first role, teaching both subjects at James B. Conant High School just outside of Chicago. Before long, Thiele noticed that science, a more traditionally academic subject, was treated with more respect by parents and fellow educators than performance-based classes such as music.

But like the Scouts’ microcredential system, Thiele says the method of music education made more sense to him. “Classes like art, music, P.E.—students have to actually demonstrate what they have learned,” he says. “But then over in the science classroom, they take a multiple-choice test and it’s run through the Scantron machine. And that’s supposed to tell me if they know science?”

So Thiele started incorporating more hands-on lessons in classes like geology. If they were studying rocks and minerals, for example, he would ask his students to demonstrate mastery of certain learning objectives—like identifying common minerals—by identifying actual rocks and minerals, not by shading in circles on a test. He found that students learned subjects better—and faster—with tangible lessons.

Which is not to say Thiele eschewed traditional lessons entirely. His science classes influenced his band classes as well. “My music instruction was more academic than some of my peers. Even in the band room, we would study music theory,” he says. “I had conversations with kids in a band setting that were very academic, but to me those things blended.”

A Bird’s-Eye View

Another subject that held Thiele’s interest from a young age was technology. “I was always really geeky,” he says. When computers started to show up in schools, Thiele became a technology coordinator at Conant. “This is when you still wheeled computers out on carts,” he laughs. At first, the position was voluntary—helping out fellow teachers where needed and figuring things out as he went along. After eight years he moved from teaching into an instructional coach role, but he continued to run the tech department at the same time. He says he viewed many of his responsibilities as a coach “through a tech lens,” training teachers to use technology and thinking about ways it could assist with teaching.

“I was like a free agent. Wherever somebody needed help, I went and helped them. And my understanding about how teachers worked exploded. I started to better understand teaching as a whole,” Thiele says. After a few years as a coach and running the tech department at the building level, he accepted the director of technology position in Maine Township High School District 207.

One of the very first technological hurdles Thiele encountered at Maine was the lack of an effective system for messaging students. “It was like sending memos back and forth to each other electronically,” he says. “One of the first things we identified was that we needed an email system for students that actually worked.”

Thiele had been keeping a close eye on the development of Google apps for some time, seeing the potential to use these free tools in a K-12 setting long before the rest of the field caught on. They were untested, so naturally there were some reservations among faculty and school board members—but Thiele says working in tech taught him to be experimental. “I was like, ‘Let’s just try stuff, and if it breaks we’ll try something else,’” he says. It goes back to how he operated in his classroom—trying a mastery-based approach that allowed students to learn better and faster. “If it works, great,” he says, “and if it doesn’t, we’ll figure it out.”

Maine Township started using Gmail at the beginning of the 2008 school year—making it the first K-12 school district in the nation to use Google apps. In addition to Gmail, Google offered a variety of other free products, such as a word processor and a calendar. By spring break the whole district had moved over to Google because the teachers realized the kids had better tools than they did. Because Maine Township was such an early adopter, the district soon became partners with Google. “We were influencing Google, and Google was influencing us,” Thiele tells us. As a bonus, he says the success of that experiment revolutionized the whole mindset of the district. It became: “Don’t let perfect get in the way of good.”

A Learner and a Leader

As the director of technology at the district level, Thiele moved from building to building and office to office to help solve tech issues. Over time, his role shifted to assistant superintendent of technology and learning, once again giving him a bird’s-eye view. This time, he observed how every part of a school district works—and works together. “One minute, I was working with the HR department to help them move forms to a digital format. The next, I’d be working with the grounds crew because they had a new sensor to measure chlorine in the pool, and somehow it had to connect to a computer and a network,” he says.

Thiele’s tenure in the technology field coincided with a rapid innovation period for the industry. He found there was no way a single person in an organization could keep up with it all, so he quickly learned the value of professional learning networks. “You had to have friends in the industry, in different districts,” he says. “You had to be a learner and a leader at the same time.”

In 2016, Thiele accepted the role of superintendent at his current district, Community High School District 99. Moving into the superintendent’s office was an adjustment for Thiele—he found that collaboration and crossover weren’t the norm the same way they were in tech. “That was not at all how superintendents worked. The office was very siloed,” he says. “They were afraid to talk about what didn’t work for them, but they didn’t want to share what was working either because then you might take it. There was more of this business competition mindset.”

Thiele decided to challenge the norm and ushered in a new era of transparency and cooperation among area school districts—along with a “let’s just try it” attitude toward problem-solving. So when Thiele began hearing complaints that graduates of District 99, even the most high-achieving ones, were struggling with problems like time management and decision-making at college, Thiele set about trying something new.

But the district couldn’t try a whole new approach to education while their facilities languished in the past. With Thiele’s help, the district passed a major bond initiative in 2018 to modernize district facilities and redesign both high schools in a style that supported their vision. Before their makeovers, he says, the buildings looked like schools from the ‘60s, ‘70s and ‘80s. They didn’t even have working air conditioning. Now, both of District 99’s high school campuses center around a large common area in a layout reminiscent of many college campuses, and informal gathering spaces with tables and chairs were added inside for students to use.

A World of Uncertainties

In addition to the physical renovations, Thiele envisioned a whole slew of changes to the curriculum and class schedule for District 99’s high schools, but a worldwide pandemic threw a wrench in those plans. However, as a technology professional, Thiele had learned to be nimble on his feet. “Every day something changed; everything was problem-solving in real time. Your whole district became a help desk,” he says. “As awful as the pandemic was, because I worked in tech, I was uniquely prepared for a world of uncertainties. We would think, We don’t know what we’re doing, but maybe we can make today better than yesterday.” Thiele’s particular skill set also gave him an advantage when it came to reading all of the changing requirements from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). After all, he was used to breaking down complicated technical documents and putting them into action.

Thiele shared his interpretation of CDC instructions with his peers in other districts—when he found a solution to a problem, he didn’t keep the fix to himself. He discovered that his peers became more willing to share their insights with him as well. “The best thing coming out of the pandemic was that a lot of those walls that were built up across school leaders—not just superintendents—all came falling down, and we all had to work together,” Thiele says.

Freedom and Flexibility

Thiele is very aware that students who participate in extracurricular activities or work after school have very little time to take care of all of their responsibilities. In addition to District 99’s newly renovated high schools, replete with collaborative workspaces inside and outside, both high schools adopted a new bell schedule to give students more time during lunch. Students can use that time to do homework or access any number of resources important to their academic success, health and well-being. Surrounding the common areas in both schools are a tutoring center, counseling services, the athletic department, the library and the cafeteria.

Additionally, the students (and teachers) were given a 90-minute block of free time one day a week. This gives busy students even more time to use as they see fit and frees up busy teachers to do professional development during work hours. Juniors and seniors in good standing have the option to spend that free time at the school or off campus. “In the world of work and college, people need to know when they need to be on site and when they don’t,” says Thiele.

All of these changes were designed to give students more independence—and more support should they need it. With freedom comes responsibility, and Thiele admits a few students demonstrate poor judgment about how to spend their free time. But he argues that they have to let students make poor choices sometimes to learn and grow—to figure things out as they go.

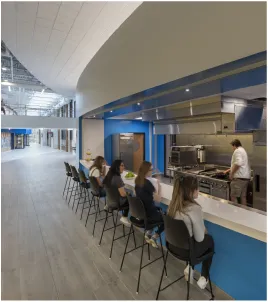

Future-Focused

In addition to its high schools, District 99 is also home to the Transition 99 Center, which offers continued educational services to 18- to 22-year-olds with special needs. It’s yet another effort by Thiele and the district to prepare all of their students for the real world. The center offers some students practice in independent living skills and provides job training for students who are more self-sufficient. For instance, students can practice working in food service roles by actually serving guests at a restaurant on campus. They can then go on to shadow restaurant workers on the job.

“I have five brothers in my family. The youngest was in a near drowning accident, and we spent our lives working through that same pathway that many students and families are working through there. It’s something that I’m very passionate about,” Thiele says. And the center has made it a district of choice for many families living outside the community. “It takes a lot of community partners, a lot of dedicated staff and the vision of a board that wants to support it,” Thiele says. “But it’s one of the crown jewels of this district. It’s a point of pride for our entire community.”

Thiele’s time in the Scouts and then as a technology expert taught him to figure things out as he goes. Of course, he needed the support of his Scout leaders and the cooperation of his tech peers to do so. Consequently, as a superintendent, he is committed to giving his students the freedom to make their own decisions—along with the tools and support they need to make smart ones. It’s a commitment reflected in the district’s strategic plan: “Future-Focused, Future-Ready.”

As Thiele prepares for his own future, he says he is proud of his accomplishments but acknowledges he is just one segment of his district’s story. “I am not District 99. I think I’ve done good work while I’ve been here, but I can only take it so far. When I retire, somebody else has got to come in and look at it differently. That’s how an organization’s supposed to grow,” he says. “The job is not about me—it’s about this community, its students, its families and what they need.”