Competing with Yourself

Managing intradistrict competition among your schools.

You’ve probably seen articles detailing the droves of students fleeing public schools for alternative education options like virtual classes and homeschooling. As to whether or not these numbers accurately represent the state of public education, the jury’s still out. One thing’s for sure, though: In the age of COVID-19 and school choice, competition is on everyone’s minds. But so much of what we hear is about competition between districts. What about schools under the same district umbrella?

If your district is large enough to have multiple schools at the same level—more than one high school, elementary school, etc.—then you’ve probably given this some thought. How can you keep your schools from overshadowing one another? How do you resist the narrative of “good school” vs. “bad school”? How do you make sure every student in your district gets the quality education they deserve without micromanaging each individual campus?

Part of the solution to building consistent excellence across your district is having each campus cultivate its own unique identity. By doing so, you encourage friendly competition between your schools, promoting innovation while still prioritizing your district as a cohesive team. Of course, in order for this to happen effectively, every building in your district must have equitable access to available resources.

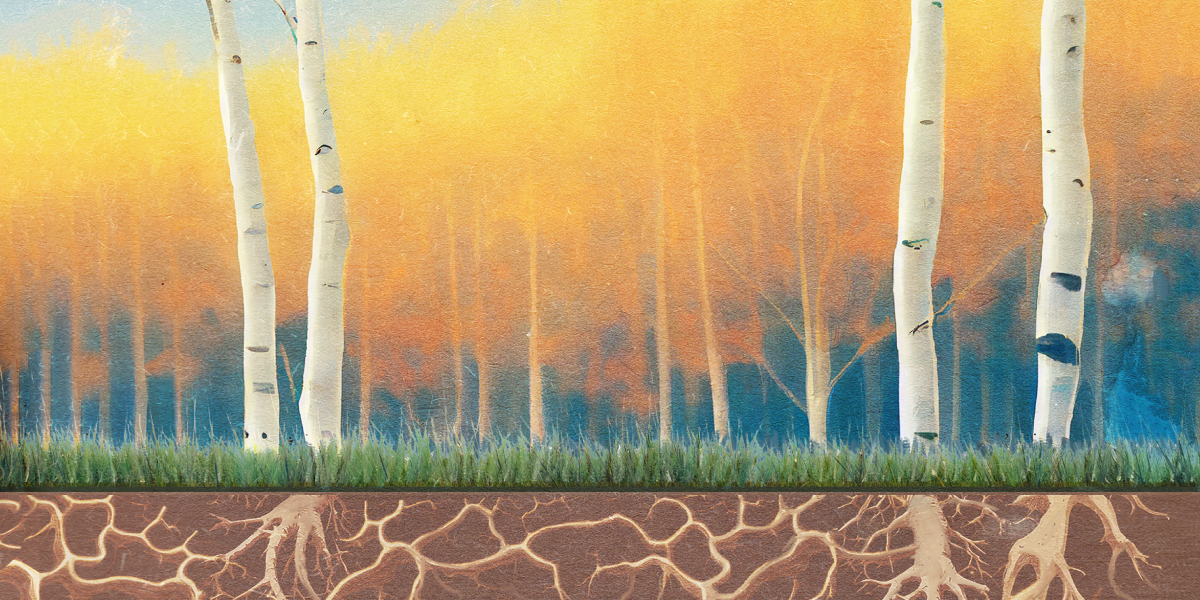

Think of your district like a grove of aspen trees. On the surface, you see singular structures standing alone. But when you look deeper, there’s an interwoven root structure tying everything together. Your schools are the same way. Each individual building is responsible for its own growth, but at the end of the day, you’re all one interconnected district—one organization. For a district to succeed, every school within it must succeed.

Studying Intradistrict Competition

While there’s substantial research into the effects of school choice between districts, there’s not nearly as much out there about the effects of competition within a district. What is available, though, is illuminating.

Take, for example, a study conducted by Lawrence Chisesi from the School of Business Administration at the University of San Diego. In his study, “Competition for Students in a Local School District,” he tracked the movement of students between elementary schools in a large district after its board implemented school choice policies. The study found that as schools began losing students to others in the district, their efforts to recruit students intensified.

Test scores didn’t have as great of an effect on families’ choices as you might think. According to the study, families who chose schools outside their own neighborhoods seemed to gravitate toward schools with higher test scores than their own—but not the schools that had the highest test scores overall. In other words, test scores matter, but they aren’t the number-one priority for families.

The study also found that families’ choices are affected by socioeconomic factors. For example, minority populations are more likely to choice into schools with student bodies that reflect the identities of their children. Another study found that families in struggling areas are more likely to choose schools outside their own neighborhoods than families in affluent areas. And when families in prosperous neighborhoods do choice out, they travel farther than folks with fewer resources.

But, according to Chisesi’s study, “The most important finding is that schools that adopted alternative programming had more success in recruiting students.” Parents seemed to be most influenced by the varying approaches different schools took to delivering the same state-mandated standards. In other words, the most important thing a school can do to better recruit students is differentiate itself from the others in its district.

What does this mean for you? It means prospective families look for schools with unique identities. It means competition can breed innovation—and it can be leveraged to bring out the best in each of your schools.

Intradistrict Competition in Action

So what does it look like to encourage individual schools to cultivate singular identities? And how can you leverage competition while still keeping your district working together as a team? Here’s how two very different districts managed to do just that.

The GISD Effect

Garland ISD (GISD) serves approximately 53,000 students and supports 7,500 staff members. You’d think it would be impossible to get every employee from the large Texas district under the same roof—but that isn’t the case. Before beginning the 2022-23 school year, GISD hosted a massive convocation attended by every single staff member.

The event was a hit—complete with drumlines, light effects, and even glow sticks. Several staff members took to Twitter to document the success of the event. One popular tweet sported the caption: “Is it a rave? No, it’s #TheGISDEffect.”

Even though the event’s primary goal was to bring the whole district together, Executive Director of Communications Sherese Nix also envisioned it as an opportunity for different campuses to show off their school pride. In the videos GISD shared, staff members dance into the arena to the beat of high school drumlines, sporting their school colors and waving homemade posters. “We had people come with their mascots. They brought their school flags, and some had all the same T-shirts on,” Nix tells us. “We welcomed that. When you take ownership and pride in your school, that resonates with the students. It creates an environment where they feel proud to come to school.”

Then, GISD turned that sense of pride into a motivator. During their convocation, the superintendent recognized every campus that had earned A’s and B’s on their state report card. One school at a time, he invited staff members from the designated campuses to stand up as the rest of the district applauded. Because not every school had earned A’s and B’s, not every school was recognized. But the superintendent reminded everyone that even if they hadn’t earned the ratings they’d wanted, they’d have another chance next year.

It would be easy to assume the campuses that weren’t recognized felt disheartened. But that wasn’t the case. “Our staff went crazy cheering and clapping for the campuses that had received those ratings,” Nix tells us. Each individual school was proud of the successes they saw around them. They fed off the celebration, determined to be one of the schools recognized at the next convocation.

By encouraging campuses to cheer one another on, GISD was using one of the oldest tricks in the book: Recognizing individual success motivates every individual to be successful. If the convocation had only addressed district-level concerns, staff members might have tuned out.

Instead, GISD intentionally created an environment where staff members felt empowered to take ownership over the work happening in their schools. Then, GISD’s 7,500 staff members went back to their respective buildings motivated to make positive change in the coming school year.

A Monticello Buckaroo

San Juan Unified School District in Utah is another large district—at least geographically. Though it serves only 3,000 students, it covers a whopping 7,815 square miles. KC Olson, principal at Monticello High School—one of San Juan USD’s five high schools—says that while district families have the option to choice into different schools, most simply choose the one closest to them. That doesn’t stop San Juan USD schools from competing with one another, though. In fact, Olson tells us Monticello’s chief rival is San Juan High School, mainly because they’re the closest—only 25 miles away.

If you were to walk through the halls of Monticello High School, you’d see all kinds of posters emblazoned with the same three words: Respect. Responsibility. Integrity. According to Olson, being a Monticello Buckaroo means embodying these three values. Monticello decided on their core values as part of a district-led initiative. Because they wanted their community to feel represented by the school’s values, they included faculty, parents, and students in the selection process.

Olson tells us that in a district as large as San Juan USD, students are more likely to identify with their specific schools than with the district as a whole. “So it’s really important that our school building also has an idea of what our identity is,” Olson says. “My efforts are focused on making students proud to be Buckaroos and giving them the expectations that come along with it.” And because those expectations are at the heart of Monticello’s brand, each student and staff member who walks through the school’s doors knows exactly what it means to be a Buckaroo. By tying everything back to their values, the school has built an identity their community can own.

As you might expect, Olson wholeheartedly believes that Monticello is the best high school in San Juan USD—and he’s always keen to prove it. Monticello often enjoys a bit of friendly competition with San Juan High. During the holidays, they compete to see who can collect the most change to purchase gift cards for under-resourced students. The winner gets to decorate a Christmas tree in the other high school’s lobby. “So if we win, they end up with an orange and black Monticello High School tree,” Olson says.

But competition between the two schools isn’t always planned. Olson and the principal at San Juan High like to keep each other on their toes. It’s not uncommon for one of them to pick up the phone and call the other with a challenge. It could be anything from a friendly bet on an upcoming volleyball game to a more academic challenge—like which school will have the most honor roll students at the end of the quarter. For impromptu challenges like this one, the losing principal’s punishment is always the same: wearing the other school’s colors for a given amount of time. In fact, each principal keeps a T-shirt from the other school in his closet at all times—just for challenges like these. But even when one school loses, it becomes an opportunity to celebrate the other school by sporting their colors. After all, they’re both a part of San Juan USD.

By creating space for your schools to differentiate themselves—whether by wearing school colors to a districtwide convocation or establishing a shared set of values—you’re setting the stage for the kind of healthy competition that can motivate your schools to give every day their best.

Remaining Unified

So what role should you play in helping your campuses establish unique identities? As a district leader, it’s your job to establish the kind of positive culture that keeps staff motivated while also promoting a sense of solidarity and shared ownership.

Think back to GISD’s convocation. Yes, individual schools were congratulated on their achievements, but every campus got fired up by the district’s collective success. The convocation never would have happened at all if the district hadn’t prioritized a culture of celebration. “We hadn’t been together as a family in four years,” Nix tells us. It was important to use the opportunity to make every staff member feel special, while also reminding everyone of the district’s central goal.

Nix also intentionally struck a balance between campus pride and district unity by doing something GISD had never done before. Instead of having a keynote speaker at their convocation, she organized the event around stories from people within the district: students, teachers, and principals. “The GISD Effect is us,” Nix says. “There is pride in the community and pride in the schools, but at the end of the day, we are all GISD, and we’re here to support all of our students.”

And what about Principal Olson’s rivalry with San Juan High School? Those friendly challenges would never happen if the principals in San Juan USD weren’t just that: friends. And that type of relationship usually results from a district culture of collaboration.

Even though Olson is determined to be number one in his district, he and other building-level leaders are always picking each other’s brains. They even read over one another’s handbooks to offer feedback on improving certain policies. “The goal is for me to take what I learn and improve Monticello,” Olson says. “And they’re going to do the same. We’re going to keep fine-tuning our practices so that our ideas and our work become higher and higher quality as time goes on.”

Pushing Each Other Forward

When it comes down to it, encouraging school pride can lead to productive, healthy competition—but the ultimate competition for each of your schools will always be with themselves. Their primary goal shouldn’t be to score slightly higher on standardized tests than the school down the street. It should be to continuously improve—to challenge themselves to keep growing.

However, that doesn’t mean your schools won’t ever rely on others in the district to keep pushing them forward. At the end of our conversation with Olson, he shared a story about his son, a three-time state championship wrestler. “His coaches told me that the only time they ever saw him mad was when his practice partner wasn’t working hard enough,” Olson says. “He’d take it as an insult.” Olson’s son knew that he could only keep getting better if his partner did the same.

Olson says that’s exactly how he sees his relationships to the other schools in his district. The success of his school depends on the success of the schools around him—it depends on everyone doing their best. “At the end of the day, I want to be better,” he tells us, “and I hope they want to be better, too—because that’s what’s going to keep driving us.”

Ultimately, pride in your school and pride in your district are two sides of the same coin, and you need both in order to promote student success. “The common denominator is our students,” Nix says, “and, as a district, if one campus fails, then we all fail.” Students are the root structure connecting each of your individual schools, and as your campuses push themselves and one another to strive for success, education will improve for every student in your district.

Subscribe below to stay connected with SchoolCEO!