Community-Powered Innovation

Charging up your community to create lasting change

Innovation. It’s a buzzword in education these days, one we throw around to describe almost any successful district. For you, the word probably calls to mind educational technology, from SMART boards to one-to-one devices to your current remote learning program. But when it comes down to it, innovation means much more than a set of flashy tools. Innovation is a mindset, a process, and a culture you can instill in your district, no matter your budget or size.

As we inch closer to a post-pandemic world, the demand for innovation in education is exploding. We hardly need to tell you that the last year has revealed cracks in the structure of the traditional public school system, from persistent inequities to flaws in pedagogy. According to research from the National Parents Union, 60% of parents believe schools should be focused on rethinking how to educate students moving forward. Simply put, there’s no going back to the way things used to be.

Your school district needs to innovate to meet students’ changing needs. But what exactly is innovation? And what does it mean to be a truly innovative district?

Innovation solves existing problems.

Dr. Lisa Dawley has been at the forefront of innovation in ed tech for over 20 years. Author of the bestselling book The Tools for Successful Online Teaching, Dawley is a Stanford Fellow and the Executive Director of the University of San Diego’s Jacobs Institute for Innovation in Education. Dawley’s team doesn’t just investigate ed tech; they examine the ingredients needed to grow innovative schools.

For Dawley, “having an innovator mindset is about viewing things as problems that can be solved.” Innovations present solutions to previously defined problems—and can be applied to solve those problems wherever they exist, even in other schools or districts.

This may seem obvious, but it’s a crucial point: Innovation for innovation’s sake is no innovation at all. Introducing a high-tech product or program just because it’s trendy won’t do anything but cost your district lots of money.

Take, for example, one-to-one devices. In the wake of COVID-19, they’ve basically become non-negotiable. But there’s a huge difference between rolling out one-to-one devices to solve problems—inequity, lack of access to lessons—and rolling them out to check a box. The former is an innovation; the latter is not.

Matthew Miller, superintendent of Ohio’s Lakota Local Schools, calls this misconception the device delusion. “So many districts purchase devices and just hand them to their teachers, who hand them to their kids, and they think that’s the end,” he says. But the devices themselves don’t solve those inequities; “they’re just the tools.” Teachers—and students—must know how to use devices effectively, or the same issues will persist. “If we didn’t have the expertise built in,” Miller explains, “we would be wasting money on a one-size-fits-all solution.” When districts blindly implement technology without considering the problems they’re ostensibly solving, those solutions inevitably fail.

Innovation goes beyond technology; in fact, it doesn’t have to involve technology at all. When you begin by asking what challenges your community is facing—not what trendy new program you’d like to implement—you’re well on your way to true innovation.

What is inclusive innovation?

Seeing innovation as the solution to a problem is only the beginning. How do you know what problems need solving or which solutions will work best for your teachers, students, and community? The answer is simple: Bring them along. “Education has a history of top-down solutions, and we know that those don’t work,” says Dawley. “If you want truly sustainable, long-lasting change, it has to be owned by the people who are experiencing the problem.”

This idea is a major driving practice for Digital Promise, one of the nation’s leading organizations in equitable school innovation. In a 2019 report on the subject, they introduce the idea of inclusive innovation, “a process of ensuring people closest to the challenge lead, participate in, and benefit from innovation.” This type of innovation doesn’t just meet its community’s needs; it values them as experts with crucial insight into the problem at hand.

Engaging your community through every step of the problem-solving process will be difficult, no doubt. But if you want solutions that work, it’s the only way to go.

Inclusive innovation produces stronger solutions.

In his book The Medici Effect, entrepreneur Frans Johansson claims to have hit on the magic formula that made the Renaissance a boom of cultural, artistic, and scientific innovation. He tells it like this: Bankrolled by a few wealthy families in the area, a flurry of sculptors, scientists, philosophers, poets, and architects descended on Florence all around the same time. “There they found each other, learned from one another, and broke down barriers between disciplines and cultures,” he writes.

Johansson believes that this space where different fields come together and combine—what he calls the Intersection—is the birthplace of innovation. The more perspectives you consider, the higher the probability that you’ll find an effective solution.

In your work as a school leader, you’re probably used to solving problems with your executive team. That team may be extremely diverse in terms of gender or race, but you almost undoubtedly have one thing in common: You’re all high-level school administrators. While you approach an issue from slightly different angles, your range of possible perspectives is still pretty limited.

Add teachers into the mix and your range of perspectives widens, though it’s still limited to the field of education. But your support staff—custodians, food service workers, bus drivers—have experience outside the classroom, opening up a completely different set of perspectives. With a wide array of careers and backgrounds, families in your district can also bring their own valuable viewpoints to the table.

Of course, your district’s students should always play a crucial role in your innovation process. At McAllen ISD in Texas, Superintendent Dr. J.A. Gonzalez knows this well. Several McAllen students from all grade levels serve as “district ambassadors,” representing their schools to the administration. “We work with principals to find students they believe could represent their schools,” Gonzalez explains. It’s not just student council presidents—it’s everyone. “We have kids from all walks of life, with regard to disability and background and socioeconomic status,” he says. “It’s a good cross-section of our student body.”

Whether you’re working with students, families, or outside community members, having that diverse representation is critical. Each new voice you add to the conversation adds a new way of thinking—and therefore new potential solutions that you and your team might never have considered. It may be a cliche, but it’s true: We are stronger together.

Inclusive innovation promotes equity.

Think back to what we said previously about your executive team. They may be diverse in terms of gender, race, economic background, and so on—but then again, they may not be. This is why it’s crucial to engage all sectors of your community—especially marginalized groups—in your approach to innovation.

Dr. Deborah Gist, superintendent of Tulsa Public Schools, has a reputation for innovation—so much so that she was named one of Time Magazine’s 100 Most Influential People in 2010. She, too, believes in letting those closest to a challenge lead the charge. But that’s a lesson she had to learn the hard way, beginning early in her career at Tulsa.

Gist saw a real problem with equity in her district: an under-resourced seventh-grade center in North Tulsa. With only about a hundred kids in the building, the McLain 7th Grade Academy was financially unsustainable—but more importantly, cost restrictions were preventing students from receiving the same quality of education as their peers at other schools. So Gist proposed what she thought was a simple solution: combining the academy with a nearby junior and senior high school.

“The reaction was so strong,” Gist tells us—strong and negative. The North Tulsa community hated the idea, insisting that it wasn’t safe and disparaging Gist for having already “made up her mind” without them. As she watched her stakeholders react to the proposal, a realization dawned on the superintendent. She’d been searching for a more equitable solution, but she hadn’t reached that solution in an equitable way.

“North Tulsa is a part of our city that has historically been oppressed, not represented in decision-making,” she explains. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, more than 35% of North Tulsa’s population lives in poverty, compared with just 17% everywhere else in the city. The area’s unemployment rate is more than double that of the rest of Tulsa. What’s more, the closure of the 7th Grade Academy would be one more addition to a long list of North Tulsa school closures, all of which had been unpopular with the community. “There was a lot of mistrust,” says Gist, “because we had not served their children well for a very long time.”

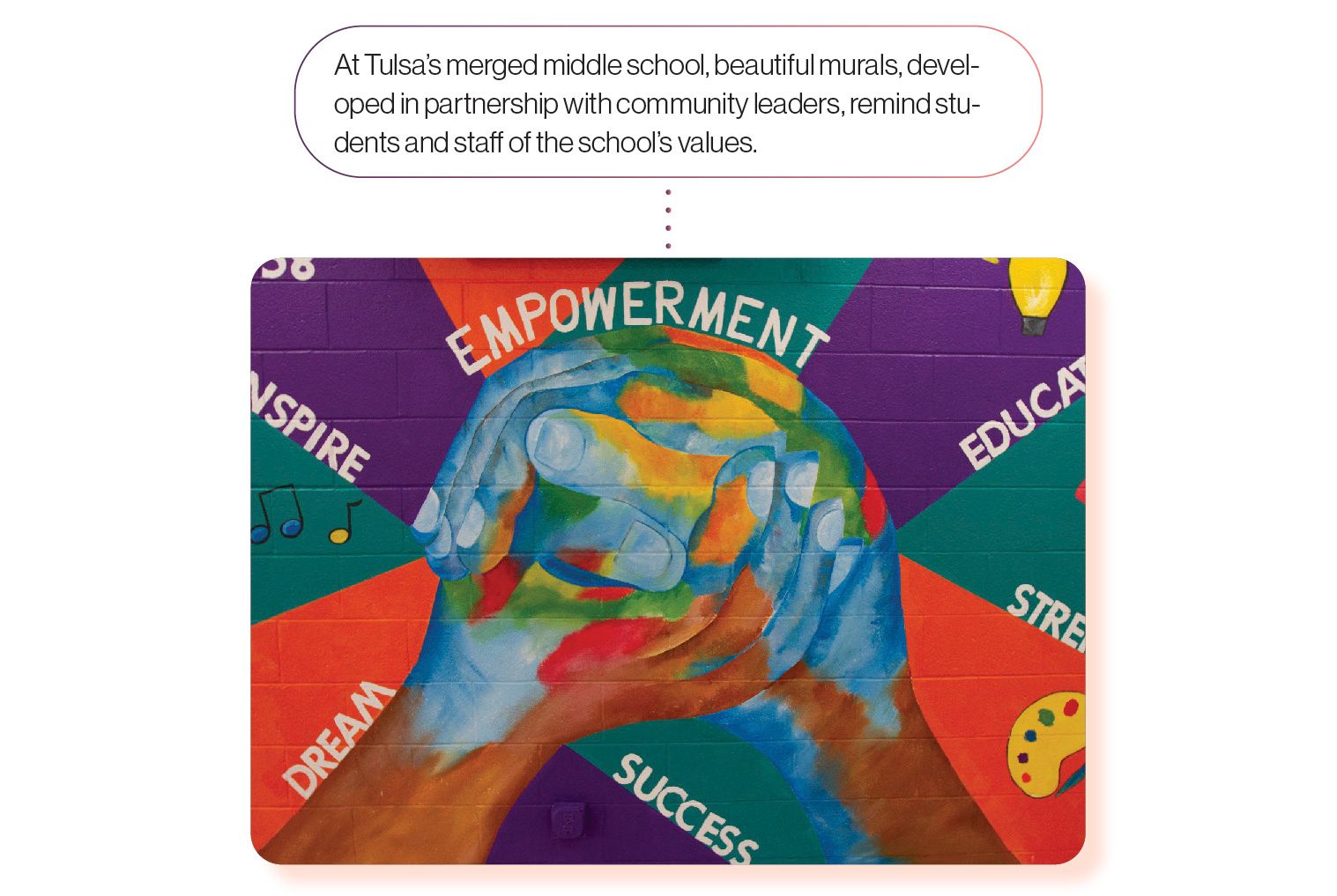

In order to find a plan that worked, Gist needed to reverse that pattern—to empower the North Tulsa community rather than leave them on the margins. So the TPS team gathered a task force of community leaders to propose their own solution. Whatever the community wanted, Gist and her team would work to make it happen.

The resulting plan looked much different—and more elaborate—than Gist’s original vision. The 7th Grade Academy was merged with the Monroe Demonstration Academy, a magnet program that became the neighborhood’s 6th-8th grade middle school. Based on the recommendations of the task force, the school now offers rich programming, including swimming, chess, debate, boxing, and dance. It even has a nearby parent resource center. Three years later, the task force is still leading and serving as a crucial sounding board for district administration.

Of course, building a new school program from scratch cost TPS a great deal more time and effort than simply shifting one grade to another building. But by letting the community lead the way, they provided an even better result for North Tulsa students—not just equity, but excellence.

In their report on the topic, Digital Promise makes an important point: “The power of inclusive innovation is that it doesn’t just invite underrepresented voices and perspectives into the innovation ecosystem; it places them at the center of it.” It empowers marginalized groups not only to express their needs, but to take leadership roles in creating solutions.

Start with relationships.

Inclusive innovation “begins with real relationships and partnerships,” says Dawley. “It’s getting out and talking to the community you’re serving, trying to understand what their needs are and what potential roles you could play in a partnership.”

More likely than not, you’re already doing this. After all, the work of a school leader is practically impossible without building strong relationships within your community. Nearly every superintendent we’ve interviewed has mentioned beginning their tenure with listening tours, serving on boards for community organizations, and visiting school campuses as often as possible.

What you may not be doing is connecting this work with the innovation process. As you learn more about what your families, students, and community members need, you’re also discovering opportunities for innovation; you’re identifying problems that need solving.

At this stage, it’s crucial to build relationships across racial and socioeconomic lines, taking care to focus on typically underrepresented members of your community. These stakeholders, more than others, are likely to have needs that have previously gone unheard.

Dig deeper.

Developing strong relationships with your community, especially those on the margins, will undoubtedly uncover challenges that need addressing. Maybe students of single parents are having trouble learning online and caring for their siblings at the same time. Maybe families who don’t speak English are facing language barriers when it comes to communication with their kids’ schools. Whatever the challenge is, now is the time to dig deeper.

“Thoroughly research the problem, everything you can learn about it,” Dawley advises. As you’d imagine, this involves a lot of traditional research: examining hard data, seeking advice from outside experts, and learning what models have worked elsewhere. But a central part of inclusive innovation is valuing and prioritizing the lived experiences of those most impacted by the problem. “That involves empathizing with them, interviewing them, talking with them, collecting data with them,” says Dawley.

Once you’ve identified a challenge that needs solving, zoom in. Leverage the relationships you’ve already developed to learn more about this specific problem. You need to understand this issue not just as a general concept, but within the specific contexts of your community members’ lives.

A few years ago, Gist knew TPS was facing a problem. In the 2017-2018 school year, the district’s graduation rate was 76.9%—up from 63% a few years prior, but still about 11 points below the national average. Only 33% of students were meeting the SAT’s College and Career Readiness Benchmarks in both reading and math. “I really believe that high schools have not worked for most kids for a long time,” she tells us.

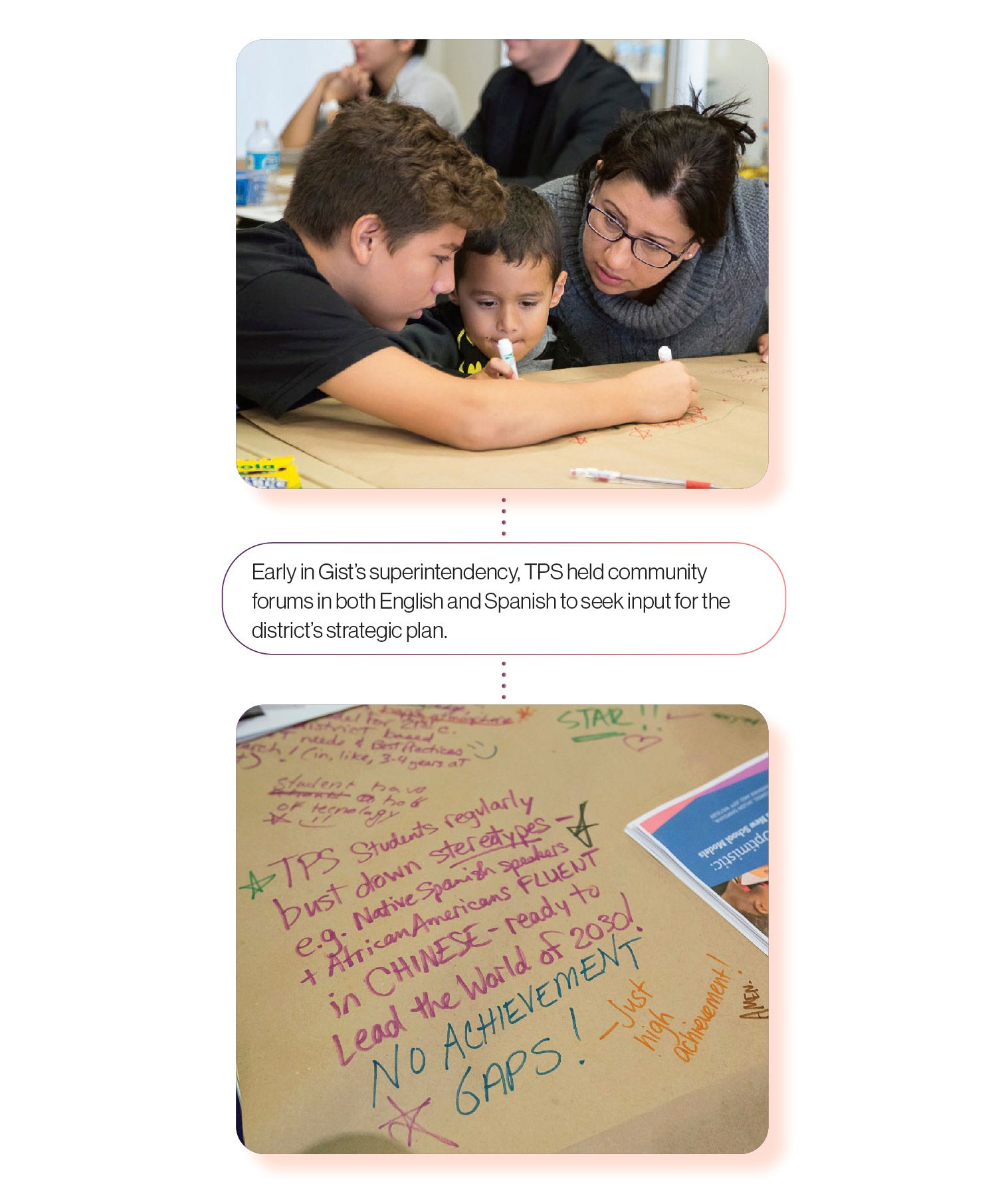

As Gist and her team began the process of solving this difficult problem, they went straight to the Tulsa community, conducting something called empathy interviews. “In the early stages, you’re really understanding people’s experiences,” Gist says—from current students to families to alumni.

TPS isn’t the first to conduct empathy interviews; they’ve long been a foundational part of design thinking processes. The idea is to have an open-ended, one-on-one conversation, discovering how someone feels about something and, more importantly, why. You keep it neutral (ask, What do you think about the way high school is structured?—not What problems do you see in the traditional high school structure?). You avoid simple yes-or-no questions. You encourage your interviewee to share stories about their experiences, not just their opinions. Most importantly, you continually ask why, drilling down into the underlying reasons people feel the way they do. This is why empathy interviews are so effective—they uncover insights and feelings participants might not have been consciously aware of beforehand.

Gist and the TPS team conducted 150 empathy interviews in their community, in addition to more traditional methods of engagement like focus groups and surveys. All in all, they received input on the high school issue from about 5,000 people—but that’s not where their inclusion process ended.

Collaborate to design solutions.

At this stage in the process, you’ve come a long way. You can be confident that you’re tackling challenges your community really needs solved, and you’ve even gained some insight into where those challenges might stem from. Unfortunately, it’s not uncommon for some school leaders to stop engaging their students and families here, satisfied that they’ve gathered enough community input. But this next step is actually the key to creating innovation that works and lasts.

It’s not enough to let your community guide you to the root of an issue. After all, the same limitations you faced at the beginning of the innovation process—cultural blindspots and limited perspectives—still exist. To create effective solutions that serve everyone, you have to engage everyone, especially underrepresented members of your community. As Dawley says, “If it’s their problem, it has to be their solution.”

After conducting their initial research, the TPS team continued down this path, including their community every step of the way. “Instead of taking that information and saying, Now we know what we need, let’s change it, we took it to the experts,” Gist says—”students, families, teachers, and school leaders.” TPS formed design teams, comprised of basically anyone in the community who wanted to join. The only prerequisite for participation was commitment to the process.

Of course, adding more people to the design process presents new challenges. How can you truly collaborate with your community on solutions without the conversation devolving into chaos?

Foster team relationships.

There’s a reason you’re tempted to make decisions within your cabinet, to consult only people you know well, to stay inside your own bubble. Our bubbles feel safe—and after all, you’ve hired a great team for a reason. Bringing together a diverse group of people with different backgrounds, perspectives, and ideas creates an environment ripe not only for creativity, but also for conflict. That’s why it’s crucial to build trust among members of your design teams, just as you would a professional team.

“At the beginning, a big part of it is team-building,” says Gist. “You want them to really get to know each other well, to understand each other’s stories, what drives them, why they’re part of the work.”

This will involve setting a few parameters on your process, not to stifle creativity, but to make sure it can flourish. “For starters, it is important to depersonalize conflict,” suggests Johansson in The Medici Effect. “People should be able to disagree with anyone in the group—but not without a reason.” Make sure your participants are offering specific criticisms of an idea, not just vague rejection. This not only makes for stronger ideas, but also keeps members of the group from feeling personally targeted.

“It is also important to maintain an open environment where all ideas get a fair hearing,” Johansson continues. This is, of course, crucial to producing stronger solutions—and, most importantly, more equitable ones. For true innovation to take place, Johansson says, “we need as many opportunities for random combinations of ideas as possible. A team of diverse people who feel free to exchange and combine their ideas is exactly what can make that happen.”

Try to say Yes.

According to Gist, a crucial part of the design process is offering your participants a “space where they can make decisions and have autonomy“—what she and her team call the sandbox. Remember, the process of inclusive innovation is about elevating your community as experts. That means valuing their ideas—not micromanaging or placing hard limits on their brainstorming. You don’t have to implement every idea your design teams develop, but don’t shoot them down before you’ve given them a chance.

At Lakota Local Schools, Miller looks for ways to say Yes to his school community, especially his staff and students. “I believe our best ideas come from the classroom—whether it’s from our kids or from our teachers,” he tells us. “I like having the ability to say Yes to educators when it’s something that’s going to both benefit their kids and make their lives easier—something that they’re passionate or excited about.” Miller trusts those ideas because he trusts his staff as experts on what their students need. “We want to invest our resources with our teachers, not some outside provider who might not know our kids or our community,” he says.

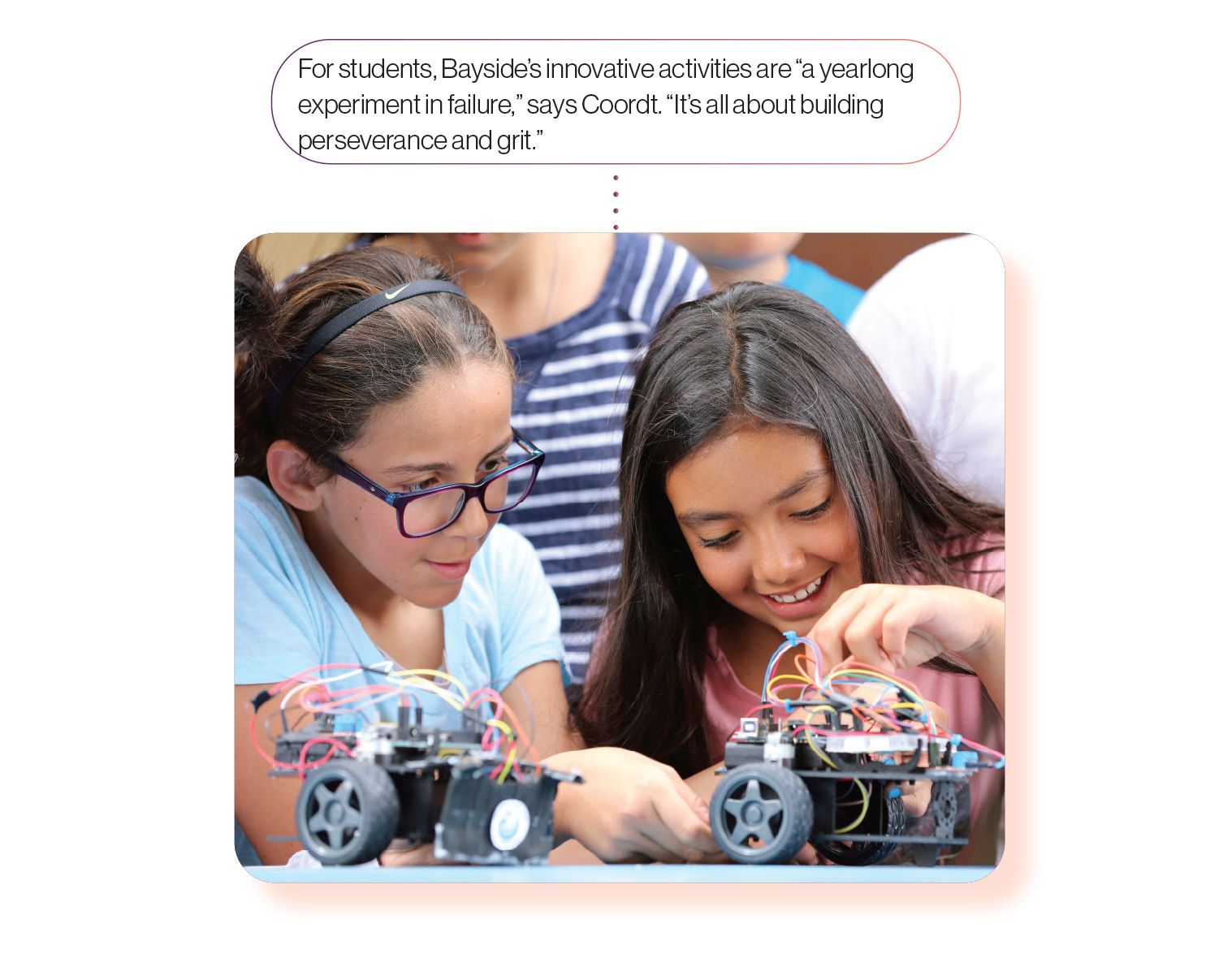

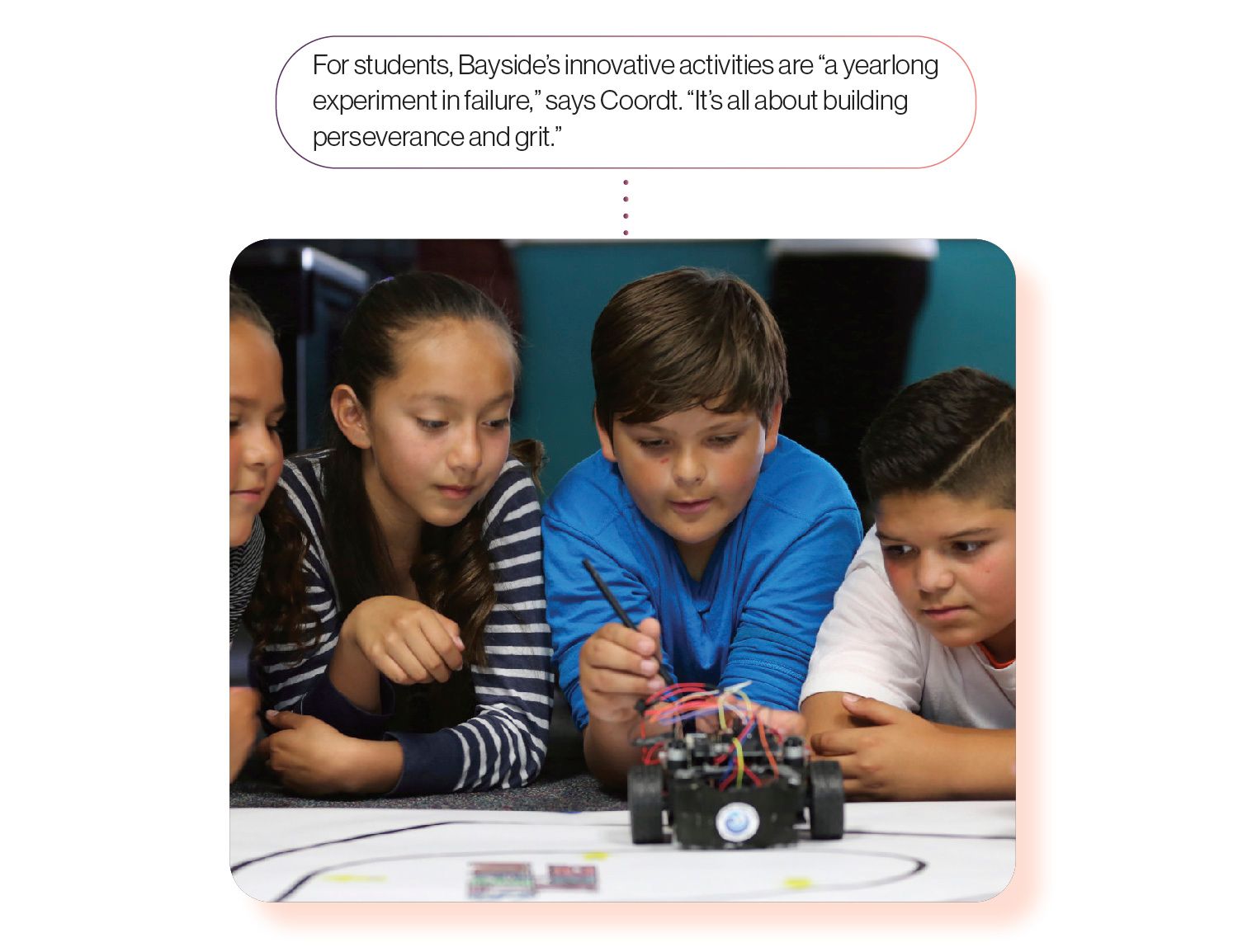

Kevin Coordt gets to say Yes more than most. As the founding principal of Bayside STEAM Academy in San Diego County’s South Bay Union School District, he’s looking for nontraditional approaches to education—and encouraging his teachers to bring their passions to the classroom.

“As we were building the Academy, some people wanted to outsource the STEAM piece,” he explains—to bring in outside instructors and programs. Bayside did hire some new teachers and silo out a few classes. But Coordt wanted all his teachers to take ownership of the new school and bring STEAM into their classrooms—even those who weren’t immediately comfortable with the idea. He started asking staff members, “What’s your passion? We’ll develop a class around that.”

So a fourth-grade teacher who loved photography ended up teaching a course on it. A kindergarten teacher even worked her love of fairy tales into STEAM engineering, building the Three Little Pigs’ houses of straw, sticks, and stone to see which stood strongest. Instead of telling his staff how to teach, Coordt lets their interests inform the curriculum—and the results are excited teachers and more engaged students.

Of course, you may have to impose some restrictions on the innovation process—and that’s okay. After all, every sandbox has walls. “It’s important for design teams to know the guiding principles,” Gist explains. “For our design team, it was basically the expectation that students be college and career ready. That is non-negotiable.” But once you’ve built your sandbox, walls and all, let your designers run free within those parameters. You never know what they’ll come up with.

Test it out.

Once you’ve collaborated with your community to design an innovation, it’s time to put it to the test. But even at this stage, your stakeholders play a key role. Who better to gauge a solution’s success than its main beneficiaries?

As we’re sure you know, no implementation process is perfect. Even a grassroots innovation, developed with your community, is unlikely to go off without a hitch right away. “The smartest managers and best-trained teams understand that failure is part of innovation, and they therefore expect it to happen a certain percentage of the time,” Johansson writes in The Medici Effect. “Many assumptions you make during development will be wrong. This is why you must not only expect failures but plan for them.”

As you implement your innovation, stay in constant communication with your stakeholders, keeping your finger on the pulse of what’s working and what’s not. Don’t hesitate to change course if your original plan isn’t solving the problem.

“I’m a big believer in changing course if things are not working out well at Lakota,” says Miller. “If we have to go back and change our initial thought or plan to make something better, I’m okay doing that. We’re not going to wait until the end of the year to fix it. We’ll fix it as soon as we can.”

At Bayside, the goal has never been to avoid failure—only to “fail forward,” says Coordt. “Some people want efficient innovation, but that’s an oxymoron, because innovation by nature is iterative. It’s full of failure, it’s messy, it’s wobbly, and we had to embrace that from the very beginning. We had never started a STEAM school before! So we just had to embrace the mess and the uncomfortableness of not knowing.”

Take, for example, something the Bayside team calls exploration time, an hour of class time where all students—from kindergartners to sixth-graders—pursue electives of their own choice. “So if you’re in kindergarten, you have four different classes you can take,” Coordt explains. “Everyone gets to pick a different class for the trimester.” Options range from a birding class in partnership with the local Audubon Society to a science course involving miniature submarines.

Understandably thrilled by the incredible opportunities they could offer kids, Coordt and his team bit off a little more than they could chew. “I think one of my particular mistakes was that I was so excited about this exploration time that I said, Hey, let’s do this four days a week, and kind of cajoled our teachers into doing that,” he tells us. “But eventually, they had to say, This is too much for us.” Coordt listened to that key part of his community—his staff. Over the last few years, Bayside has scaled exploration time back to two days a week. “That was a better, more comfortable pace for everyone,” he says.

Modeling this willingness to fail and change course is more than good strategy; it’s part of Bayside’s philosophy. As a STEAM school, they’re training the next generation of innovators—and those students need to learn early that it’s okay to fail. “We want our kids to take risks,” Coordt says. “So as the adults in the building, we’ve got to take risks, too.”

Make it last.

Like any system, product, or program, the innovations you create with your community will require constant refinement. As situations and contexts shift, you’ll need to check in with your stakeholders again and again, ensuring that your solutions are still working as planned.

But here’s some good news: Unlike most initiatives spearheaded by your administration, inclusive innovations will likely survive without you. “They become more sustainable because the people are bought in for the long term,” Dawley says. “Then your role becomes that of a partner instead of a savior.” When you retire or move on from the district, the solution won’t fall apart—because it didn’t start with you in the first place.

When you recognize your community as the experts they are and put the problem-solving power into their hands, an incredible chain of events is set in motion. Your district will solve the right problems. You’ll better understand why those problems occur. You’ll land on stronger solutions, and you’ll know how to recalibrate those solutions when they fail. Most importantly, you’ll have created lasting change in your district—because that change came from the district itself. The innovation belonged to your community all along.

SchoolCEO is free for K-12 school leaders. Subscribe below to stay connected with us!