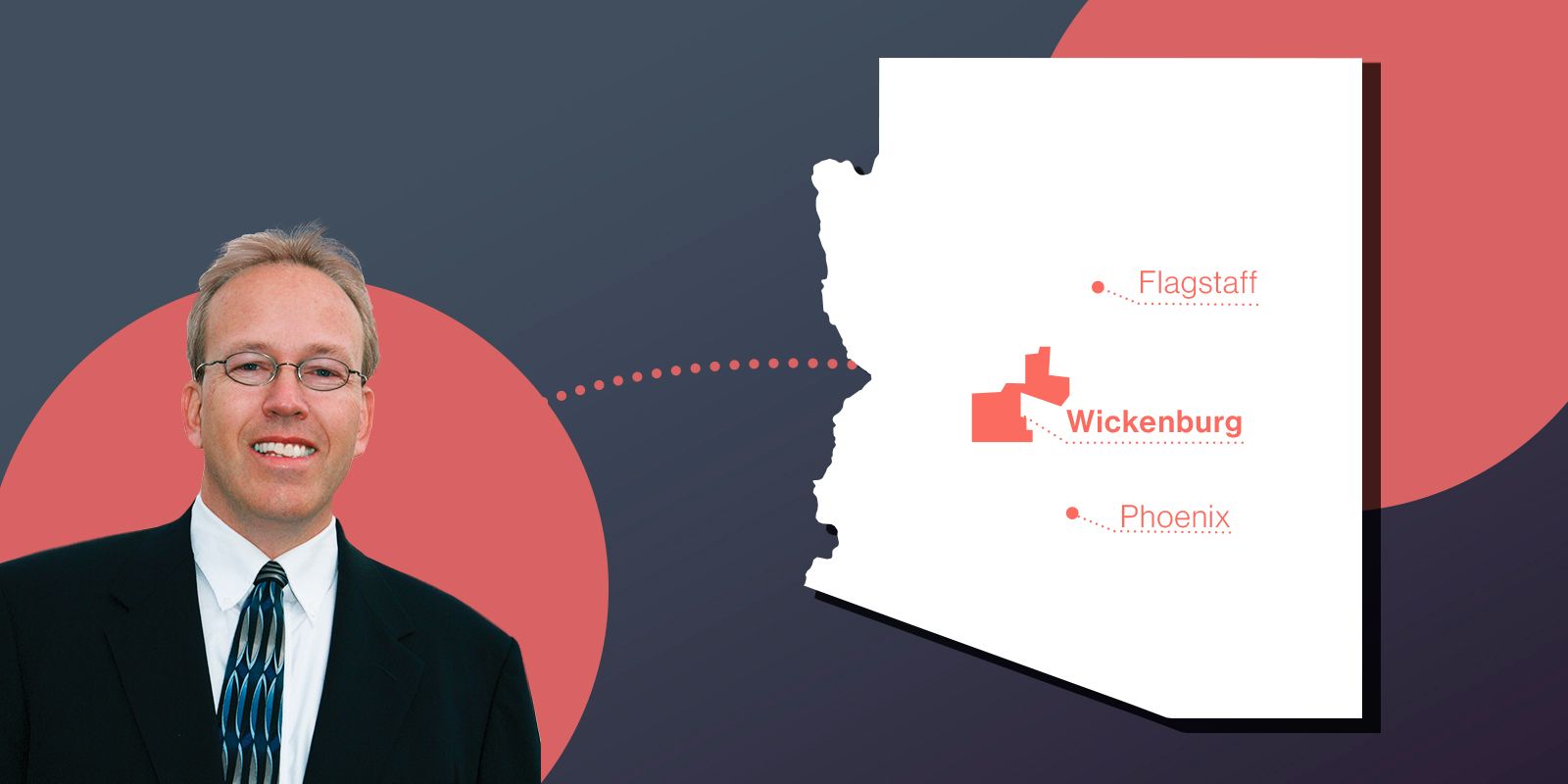

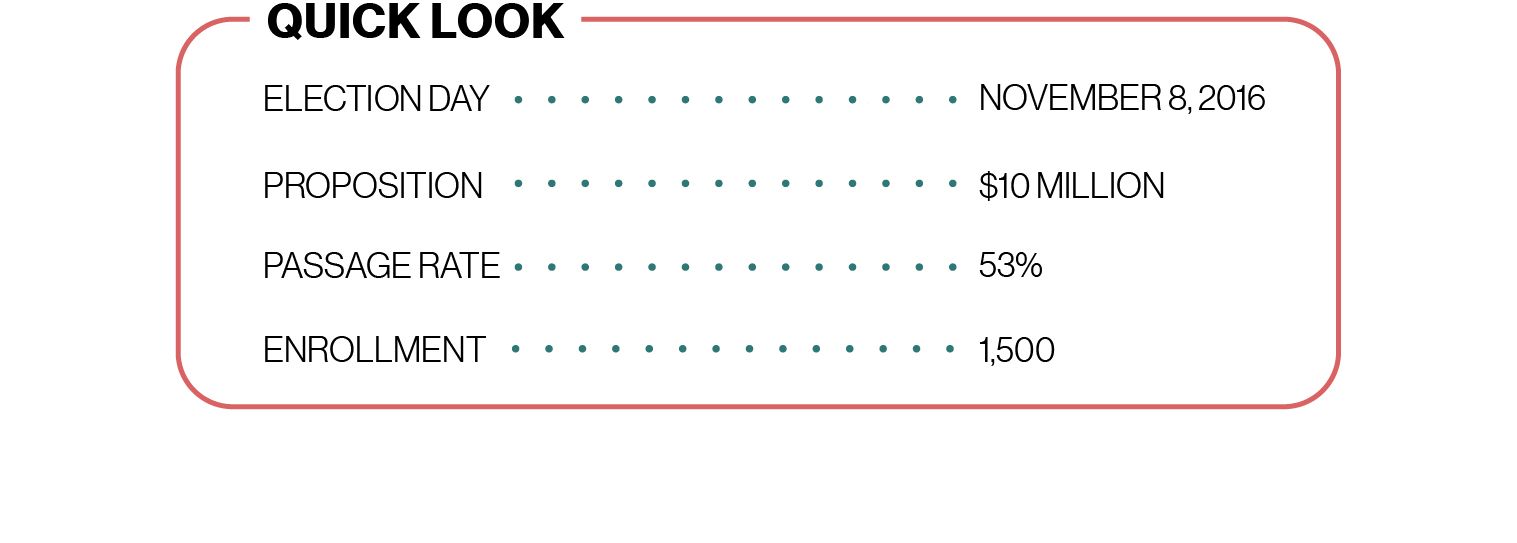

Bond Campaign Deep Dive: Wickenburg Unified School District

Recruiting the Team · Differentiating Messaging · Varying Communication Channels

Wickenburg Unified School District #9 covers an astounding 916 square miles—an area that could hold the entirety of New York City three times. And if the district’s geography weren’t challenging enough, Wickenburg also faced statewide budget cuts in 2009.

“At that time, 85% of the capital money for schools was cut,” Dr. Howard Carlson, Wickenburg’s superintendent, explains. “So districts suddenly weren’t able to take care of their repair and maintenance needs or replace equipment.”

In the years following the cuts, Wickenburg’s oldest facilities and equipment began to deteriorate. “We started to talk about the health and safety needs of the district,” Carlson says. “We had buses breaking down, stranding kids in the middle of the night coming home from a football game. We had air conditioning that was 21 years old.”

Something had to be done, so Carlson and his team started discussing a bond. Because of the district’s size, the team would need to consider two very separate communities. “The northern part of the district is a group that, in large part, is not as affluent,” Carlson tells us. The southern part, however, is home to a large population of retirees. Residents of the local retirement community are generally college-educated and tend to have more expendable income.

“You can’t treat all groups in your district equally; rather, you have to treat them equitably.”

Because of the differences between these two communities’ needs, Carlson knew that a one-size-fits-all strategy wouldn’t work for Wickenburg. “You really run two

different campaigns based on the geographic scenario you’re dealing with,” he explains. “By and large, those groups are separate entities. We were working with different people and tailoring different messages based on the two areas.”

Beyond location alone, the district also needed to communicate with different generations and demographics. Luckily, having served 17 years as a school superintendent, Carlson is no stranger to bond elections. He’s led different campaigns across states, even sharing his experience at a state conference with bond expert Dr. Don Lifto (check out SchoolCEO's interview with Dr. Lifto here).

Lessons from Wickenburg:

- Recruit an all-star team in your schools and beyond.

- Differentiate messaging.

- Vary communication channels.

Recruit an all-star team in your schools and beyond.

To Carlson, a successful campaign is all about who’s delivering your message. “When it comes to a bond or tax initiative, there’s an inverted pyramid,” he explains. In most cases, people would be listening to the superintendent. But in the case of a bond, the opposite is true. “They’re listening less to me because I’m the professional educator, and more to the bus driver or the food service worker or the custodian.”

To find what Carlson calls “key communicators,” the district looked for formal and informal leaders from different voting groups. The team consulted school board members, colleagues, and other community members. Then, to recruit, they paired with an influential member of the targeted individual’s community to make the ask. Generally, recruits were more likely to accept when asked by someone they knew beforehand.

Carlson was also mindful of district staff. “What we did,” he tells us, “was make sure from an internal standpoint that we were getting out to each employee group, making sure they had the correct information, and answering any of their questions so that, in the end, they could be our key communicators.”

When the planning process came to a close, the district had accumulated quite a team of supporters. “We really ended up with two PACs—a northern and a southern one,” Carlson tells us. Two separate PACs meant two separate campaigns with unique messaging.

Differentiate messaging.

Carlson’s team took their time developing the campaign’s core messaging. “We tried to show how the bond would benefit our kids,” he explains. They focused on safety, even calling the measure a “Health and Safety Bond.”

“Obviously, that was branding,” Carlson says. “There’s no such thing as a health and safety bond in Arizona, but we used that as a marketing strategy to categorize it and give it meaning.”

This core message became a compass to formulate messaging that better fit each of Wickenburg’s local communities. Instead of guessing what each community valued, the district conducted surveys. “You have to make sure you’re looking deeply at the data in order to ultimately get your message out,” Carlson explains. They found that messaging that garnered a positive response in the northern part of the district effectively bombed in the southern section.

“The tax piece was definitely an overarching item to focus on in the northern part of Wickenburg,” Carlson explains. “In the southern part, the message was more balanced.” With a higher population of educated residents with more expendable income in the southern section, messaging was focused less on the bond’s tax impact and more on an opportunity to support students. This group, Carlson says, was also more likely to care about problems that affected students—like a bus breaking down with kids on board.

Carlson also kept various demographic groups, like retirees and parents with young children, in mind. “We then differentiated and broke down the different groups in the district demographically and developed marketing strategies for each,” Carlson explains.

Ultimately, the district ended up delivering messages specific to retirees, families, and the greater Wickenburg community. “As an example, retirees were most concerned about taxes. So, we talked about taxes with them,” says Carlson. “For families, it might have been related to the fact that we want to keep their kids in a good learning environment.”

Still, targeted messaging was only the starting point in Wickenburg’s communications strategy. Throughout the campaign, Carlson was also conscious of ways different groups receive information.

Vary communication channels.

“In this day and age, we need to understand that you have multiple generations out there,” Carlson explains. “From Baby Boomers all the way down to Generation Z, the bottom line is that each of those groups consumes and gathers information in different ways.”

For Carlson, distinguishing between these groups is vital for any bond effort. “You have to differentiate,” he says. “You can’t treat all groups in your district equally; rather, you have to treat them equitably.” That way, various groups in your community are getting the same information, but from different platforms.

“It was a matter of looking at how each of those groups consumes information, and then making sure we used the proper channels to get them the information that they needed,” Carlson explains. For retirees, the district focused on print media. They shared videos on social media to engage younger families. To reach the broader community, the Wickenburg team connected with service groups like local Rotary clubs and chambers of commerce.

Wickenburg also targeted key communicators in every sector, asking community leaders to give informational presentations on the district’s behalf. “We understood that those groups relate more to their own people than to someone from the outside,” says Carlson.

The district’s job, then, was to prepare materials for those community presenters that were factual, accessible, and easily understood. “Bottom line, we were producing information that could be used publicly by the district, and then the presenter could speak to it from there,” Carlson says. Sometimes, this meant adjusting materials to fit the community’s needs.

To engage Wickenburg’s Hispanic community, for example, the district translated materials into Spanish. Presentations were also given by key communicators

from within this community—“individuals who were well-respected,” explains Carlson, “because we wanted to make sure we had key communicators who were a part of this committee and the PAC.”

At Wickenburg, adjusting communication tactics to fit the community’s needs isn’t limited to a referendum campaign. “It’s not just bonds, levies, or overrides,”

Carlson says. “It’s a shift in how districts should communicate. They now have Facebook and Instagram and Twitter, but they are not strategically looking at how the messages might differ between a 45-year-old and a 23-year-old.”

It goes back to making sure all stakeholders can connect with the district, he explains. “Because that’s how you provide equity.”

SchoolCEO is free for K-12 school leaders. Subscribe below to stay connected with us!