Dr. Carol Kelley: A Space for All Learners

How Dr. Carol Kelley is building equity in a diverse K-8 district

How Dr. Carol Kelley is building equity in a diverse K-8 district

Dr. Carol Kelley had never planned on becoming a teacher. In the early ‘90s, fresh from an M.B.A. program at the University of Virginia, she had landed a job in New Jersey, working in project management at Johnson & Johnson. She was a successful engineer with two degrees under her belt, but her heart was somewhere else.

“As I got into my mid-20s, I just wanted to do more to make our society better,” Kelley told SchoolCEO. “I was doing a lot outside of work, volunteering"—tutoring and mentoring boys from a nearby middle school who had been expelled for fighting.

Kelley says she’s always been “intrigued by the potential of public school.” She knows the system can work, because she’s personally experienced its benefits: invested teachers and mentors who saw her potential and gave her opportunities to succeed. “But I think it worked for me because I was able to fit,” she says. And as she saw firsthand through her volunteering, not every kid fits.

When Kelley’s book club read Jawanza Kunjufu’s book Countering the Conspiracy to Destroy Black Boys, it all came together for her. “Research was showing that these kids were coming into schools really enthusiastic, but over time, by fourth grade, they were totally disengaged, didn’t like school, had poor performance, high discipline rates,” she says. She knew it wasn’t the kids that were broken, but the system.

That’s why she ultimately felt called to teach: ”to create spaces where all learners could be successful.” In 1994, the principal of her local middle school—the same school that had expelled the boys she volunteered with—offered Kelley her first teaching job.

After seven years in the classroom, Kelley took an administrative position in her district. From then on, she ran the gamut through school administration: dean of students, principal, math supervisor, director of curriculum instruction.

In 2002, she returned to her undergrad alma mater, the University of Pennsylvania, to pursue a doctorate in education.

“I was not interested in the superintendency," Kelley told us—at least not initially. She had planned to apply for assistant superintendent of curriculum instruction, but a mentor encouraged her to go for the open superintendency at Branchburg Township Public Schools. She got the job, and brought her passion for equity with her.

“I started my first superintendency sort of as I did teaching, not because I was really seeking that position, but because of the promise of public schools,” she says. “My work has always been to try to create what I had for all kids, not just kids that fit in.”

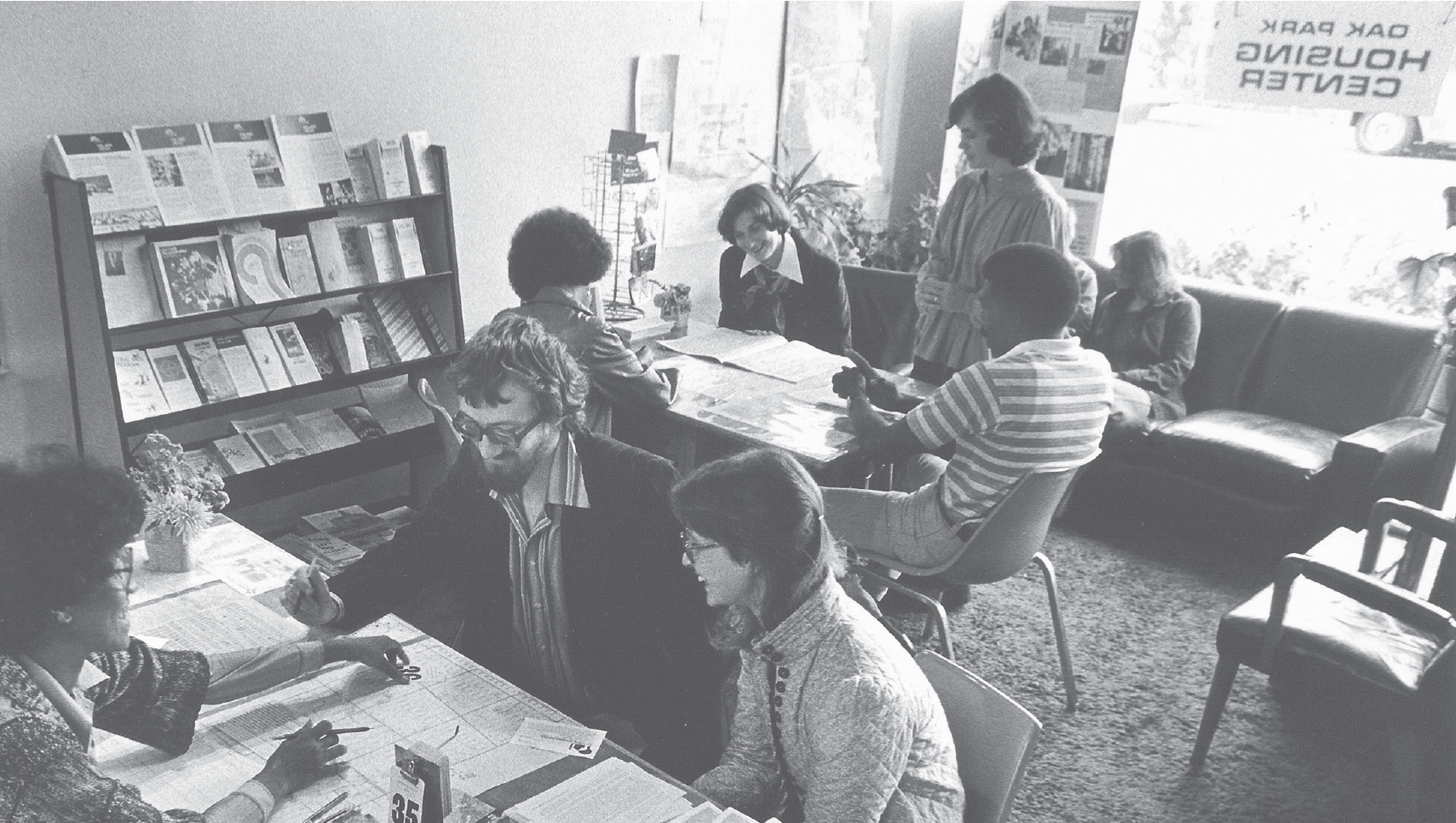

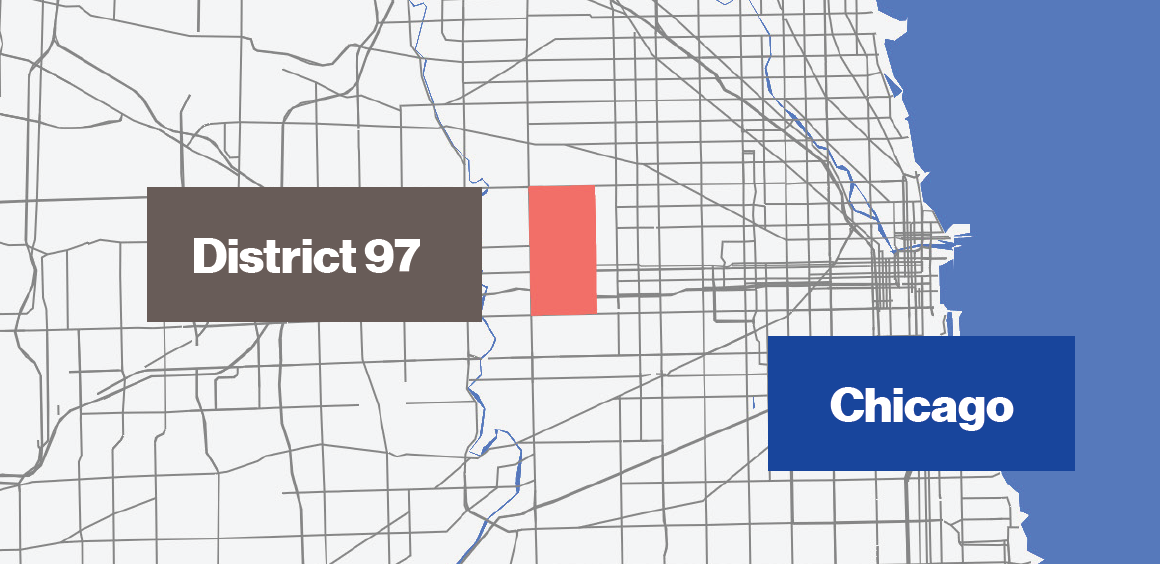

The issue of equity is baked into the history of Oak Park, Illinois, a village on the west side of Chicago. In the 1960s, neighborhoods around Oak Park—like nearby Austin—faced "white flight" and resegregation when they attempted to integrate. Many residents who were passionate about equity suspected that unless they intervened, Oak Park's integration would fail as well.

In 1968, Oak Park passed a fair housing ordinance, outlawing discrimination in the housing market. Beginning in 1972, the Oak Park Regional Housing Center worked to expand housing options for minority families and fight segregation. The result, 50 years later, is an extremely diverse community, socially, economically, and racially. Its schools—including Oak Elementary School District 97—are no different.

When Superintendent Al Roberts announced his retirement from District 97 in 2015, the newly open position caught Kelley’s eye. She had been at Branchburg for three years, but this Illinois district offered “the potential for transformative change," she says, "which is what you need for an equitable and inclusive community."

Once the job opened, 48 candidates from 11 states applied to be District 97’s next superintendent—including Kelley. That June, she got the job. The school board’s decision was unanimous.

“She strikes me as an individual who leads with integrity, one who’s committed to equity and excellence,” Roberts told the Chicago Tribune after Kelley was hired. She's proven herself to be just that.

Household Income Distribution of The Village of Oak Park — 2018

From the beginning of Kelley’s tenure at District 97, she’s prioritized equity. “For me and for the district, equity means attempting to provide a learning environment—a culture and a climate—where every student can reach their fullest potential,” Kelley says. In a truly equitable school, she explains, neither race nor economic background nor neighborhood should be reliable predictors for a student's academic performance. Every kid should feel that the faculty sees their potential, and that support should drive students to believe in themselves. Most of all, all students should feel "that they are welcome and that they have a sense of belonging,” Kelley says.

Equity is "not the same as equality, where you’re trying to provide the same experience to all students,” she points out. “We’re trying to give all students what they need to be able to be successful.”

It might sound simple, but the reality of creating this kind of environment is much more complicated. “I think one of the challenges for all schools, but particularly here at Oak Park, is that the school is just an example of the larger picture of society in America,” Kelley says. “There are institutional systems in place that prevent students from experiencing life in general the same—whether it’s housing, whether it’s healthcare, whether it’s the employment market.”

Those same institutional barriers bleed into the school system. Take the issue of tracking, for example. Study after study shows that even at diverse and nominally progressive schools, AP and honors classes are filled with predominantly white students, while students of color remain behind on the basic track. Examining these patterns in their book Despite the Best Intentions, researchers Amanda E. Lewis and John B. Diamond consider the historical basis for tracking.

“The history of tracking in American public schools is rife with racist strands, deeply connected to Social Darwinism and the eugenics movement,” they write. The prevailing belief that non-white, low-income children had less intellectual potential than their white, affluent counterparts drove schools to create separate, more “proper” tracks that prepared these students for the workforce, not further learning.

Population Breakdown by Race

Although the language we use to talk about and justify tracking has changed today, the effects are, for the most part, the same—even in diverse districts like Kelley's. “In many instances, because of the systems that are in place in our schools, we basically reproduce the inequity we see in society as a whole,” Kelley says.

This issue reared its ugly head in the district’s Gifted, Talented and Differentiation (GTD) program in 2017. According to Oak Park's Wednesday Journal, only 10 of the program’s 329 students that year were black. Just 14 were Latino; 219 were white.

In August 2017, Kelley got to work. With the help of an outside expert, she formed and facilitated an ad hoc committee, made up of parents and community members, to analyze how the GTD program selected students. The district began requiring cultural competency trainings for its teachers. Instead of shuffling GTD kids away to separate classrooms, teachers began giving their specialized instruction in the regular classroom, allowing students who aren’t in the program to benefit as well.

The GTD program brings up an important point, one central to Kelley’s approach to equity: it’s not kids that need to be “fixed.” It’s the system itself.

“To eliminate the inequities, it takes some systemic examining,” she says. “What are the barriers causing these large gaps? Let’s break down those barriers.”

Social psychologist Claude M. Steele takes the title of his book Whistling Vivaldi from an anecdote by Brent Staples, a columnist for the New York Times. As a young, black graduate student, Staples found that when he walked down the streets of Chicago’s Hyde Park at night, negative stereotypes flurried around him. “I became an expert in the language of fear,” Staples writes. “Couples locked arms and reached for each other’s hands when they saw me. Some crossed to the other side of the street.”

Of course, Staples meant no one any harm—but because of powerful stereotypes, people in Hyde Park expected young black men to be violent, dangerous. This not only kept Staples from moving comfortably through the world, but also damaged his self-concept. “I did violence to them just by being,” he writes. So he found a way to deflect the stereotypes: he walked down the street whistling classical music. When he did this, “the tension drained from people’s bodies,” he says. “A few even smiled when they passed me in the dark.”

Negative stereotypes exist everywhere. And as Steele goes on to explain in Whistling Vivaldi, the fear of conforming to a negative stereotype about one’s social group—whether it’s race, class, gender, or something else—can lead to poor performance. Kelley is determined to mitigate the effects of stereotypes in her district.

This school year, District 97 is reading Whistling Vivaldi as a district. Everyone from administrators to students to parents is invited to participate. “It’s been a really good book for us to explore how stereotypes, or even the things students have in their minds about themselves, can threaten them from putting themselves out there in the classrooms,” Kelley says. Through a “slow chat” on Twitter, she’s encouraging the community to engage with the book, and directly apply its lessons to the district. “Black students at one small prestigious campus that Steele visited gave him the sense that ‘campus life was racially organized,’” one tweet reads. “Is D97 also ‘racially organized’? Where, specifically, can you see that?”

Kelley has already begun incorporating some of the book’s ideas into district programming. For example, Steele suggests that to break down stereotypes, students of different backgrounds need to interact with each other.

“He was sharing these examples of study groups,” Kelley says. “The black students in his graduate program were thinking they were the only ones struggling with the learning material.” But in the integrated study groups, they learned this wasn’t the case; the white students were struggling just as much. “It helped them break down the myth they had in their heads,” Kelley says—the idea that the white students were somehow smarter or more capable.

So in District 97, Kelley is spearheading more ways to bring students together. Alluding to its mascot, the hawk, Holmes Elementary has started “nests”—small meeting groups made up of students ranging from kindergarten through fifth grade, led by a faculty or staff member. Other schools are implementing mentoring programs to get kids to venture beyond their cultural comfort zones. “We’re just trying to break down the barriers that sometimes exist even with the kids, where they don’t go outside their circles,” Kelley says. “Helping them to expand their circles, so they can demystify some of the myths they’ve heard about students of other cultures”—and about themselves.

Kelley’s advice to other school leaders who want to build equity in their districts? “Pray for patience," she laughs. It might be easier for people inside an organization to make changes, but if (like her) you’re coming into your district from the outside, it will take time. “You’re going to have to spend a lot of your time just building social capital in the community,” she says.

Even four years into her superintendency, Kelley is still continuing to build that social capital. She hosts monthly Community Cafe events at local coffee shops, and actively promotes the district on Twitter.

“I look at what I’m doing on Twitter as being a classroom teacher, but my students now are the community,” Kelley says. “It’s an opportunity for people who follow me to learn about what we’re doing and why it’s important.” She gives the example of Holmes Elementary's "Leader in Me" program, designed to build more equitable environments by helping students advocate for themselves. “When I say, ‘We’re really trying to help students use their voice,’ that’s hard,” she says. “You can communicate the vision, but sometimes people need to see actual examples of what it looks like.” When community stakeholders get those concrete examples, they trust Kelley, and the district, more.

Kelley also emphasizes the need for a support system external to the district: other superintendents and school leaders embarking on the same kind of equity work. “You’ll need a support team,” she says—people who can provide you with not just technical resources, but encouragement and a listening ear.

But what you need more than anything is drive—something Kelley certainly has. You can hear it in her voice, the way she talks about the kids, every kid. You can tell she feels a sense of responsibility to the work.

“I believe every person has a gift, something that’s intended to help others,” she says. “I think this might be my gift."

SchoolCEO is free for K-12 school leaders. Subscribe below to stay connected with us!