Dr. Joe Gothard: A Place to Call Home

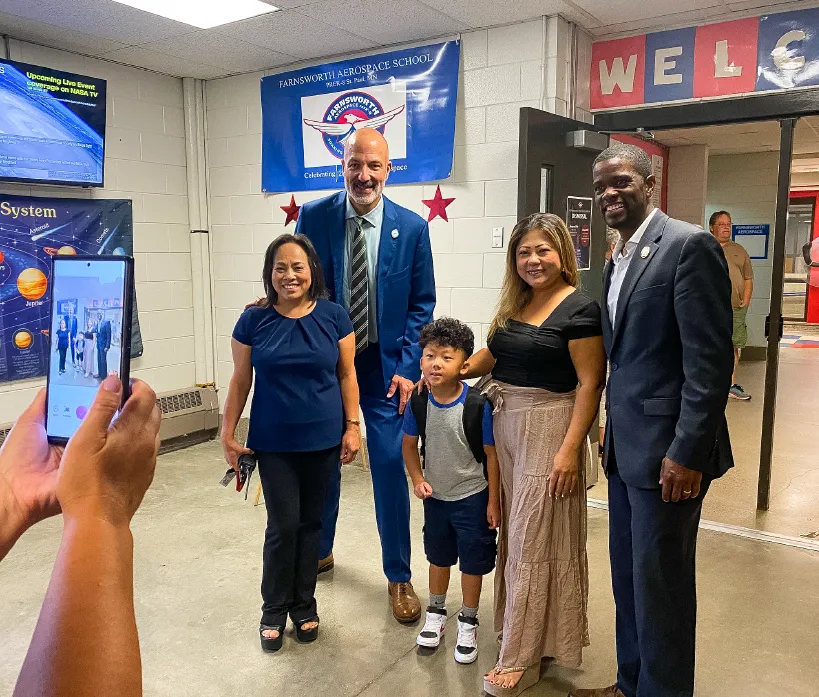

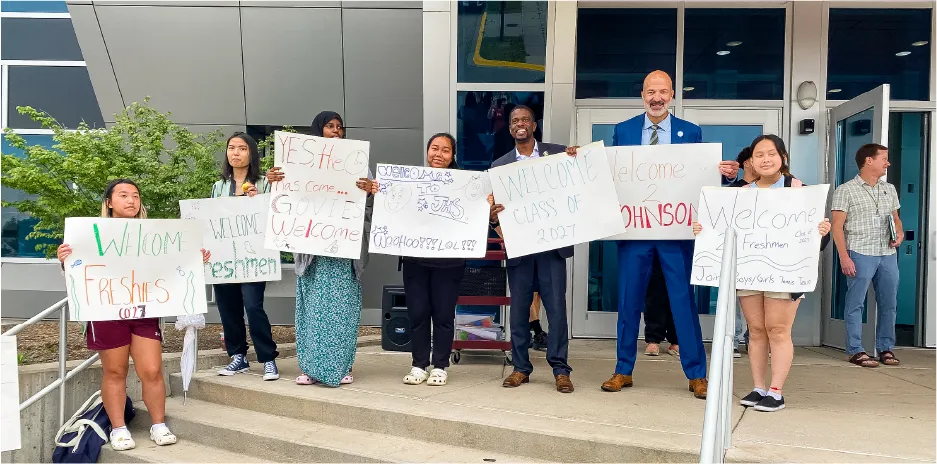

How Dr. Joe Gothard is meeting needs and building belonging in Saint Paul Public Schools

When Dr. Joe Gothard laid eyes on the city of St. Paul, it was love at first sight—or at least something close. “I’ll never forget it,” he says. “I was driving to a meeting, and all of a sudden, I look over, and there’s the Capitol.” Growing up one state away in Madison, Wisconsin, Gothard was, as he puts it, “a capital city kid.” And looking up at Minnesota’s State Capitol building, he felt strangely at home.

Now, Gothard is in his seventh school year at the helm of Saint Paul Public Schools (SPPS) and his 30th in public education. It makes sense, really, that he went into teaching. After all, school was one of the first places he ever felt comfortable—in his own skin or in the world around him. “It really begins with my middle school teacher, Lois Bell, the first and only Black teacher I ever had,” he tells us. Her influence was eye-opening for Gothard, the child of a white mother and a Black father. “She was able to help me confront my racial identity in a way that nobody had,” he says. “It’s a defining moment in my life.”

Following his teacher’s example, Gothard has made a career of seeing and meeting students’ unique needs. That work has garnered attention from both local and national media, and in December, he was named a finalist for AASA’s National Superintendent of the Year. In St. Paul—the site of the nation’s first public charter school—Gothard has learned that being inclusive of all kids isn’t just the right thing to do; it’s also the best way to compete. That’s why he’s striving to create a district where any student, regardless of their background, can feel at home.

Alma Mater All-Star

Gothard began his career at his alma mater, Madison’s Robert M. La Follette High School, teaching biology and coaching football. “Gosh, I loved it,” he says. “I mean, I got to teach in one of my former classrooms. I think back now, and I’m like, Why did I ever leave that?” And truth be told, he didn’t really intend to ever leave teaching. “It was never part of my plan to become a principal, an assistant superintendent, or a superintendent,” he says. “But my home community saw something in me, and they convinced me that I could lead.”

One of those community members was Dr. Mike Meissen, the principal who had hired him at La Follette. “Dr. Meissen saw in me an ability to have a deeper reach in the school community in terms of leadership,” he says. So when Meissen recommended he leave the classroom, take on a new role as dean of students, and start working on his master’s, that’s just what Gothard did.

From there, Gothard continued to grow and take on new challenges, all within the warm embrace of his hometown. He worked as a middle school principal for two years—a “humbling experience,” he says—before returning to lead the school he’d graduated from. With the encouragement of two other mentors, Dr. Pam Nash and Dr. Jane Bellmore, he began working toward his doctorate and superintendent certification. Then, after four years as principal at La Follette, he became the assistant superintendent of secondary schools at Madison Metropolitan School District.

Gothard hadn’t been in that position long before a new opportunity emerged. “The superintendent I worked for in Madison was caught in some really difficult and challenging work,” he says. “Community groups were not on the same page, and the board became divided as well.” After Gothard’s second year there, that superintendent left, leaving the top job open. “So of course,” he says, “I decided to apply.”

That would have made a great ending to the story—a hometown kid, the first in his family to go to college, becoming the superintendent in the district where he grew up. But it just wasn’t in the cards. The position went to someone else.

“I was really at a crossroads in my career,” Gothard says. “Did I want to stay and work with the new administration, or did I want to look for other opportunities?” Would he stay in the community that had raised him or move his three kids away from their home—from his home?

As Gothard puts it, “I’ve always taken the leap to learn and grow.” It was time to take the lessons he’d learned at home and bring them somewhere new.

A New Home

The following year, Gothard found himself in Burnsville, Minnesota—“a place I’d never heard of,” he says. “But in looking at their district, the characteristics made me feel like this was somewhere I could go and learn and lead.” He accepted his first superintendency at Burnsville-Eagan-Savage School District 191, just outside of St. Paul. “I had four incredible years there,” he says, “learning how to be a superintendent, immersing myself in a new community, and doing some pretty exciting work.”

Once again, it wasn’t Gothard’s intention to leave—but opportunity came knocking. At District 191, he had quickly established himself as a transformational leader, someone who could heal divides and unify communities around a common vision. “I was in the first or second year of a new contract when the St. Paul position became available, and many people in this region really wanted me to apply,” he says. In 2017, he took the helm as superintendent of SPPS, and he’s been there ever since.

It wasn’t just the familiar feel of a capital city that drew Gothard to St. Paul. “The racial and cultural demographics of St. Paul really spoke to me,” he says. The Twin Cities metro area is well known for its cultural diversity. In fact, it’s home to the country’s largest urban population of Hmong Americans, as well as the nation’s highest concentration of Somali Americans. And the district is no different; the majority of students at SPPS are people of color. “We have over 125 languages spoken in our schools,” says Gothard. “It truly is a global school district.”

And SPPS sees their diversity for the asset it is. “The diversity does make us much, much stronger,” Gothard says. “One of our greatest strengths is the way this community embraces and manages dynamics of difference. In some places, that would be a call to divide, but that isn’t how things happen in St. Paul. We really like to come together.”

But Gothard was also attracted to the challenges his new district would present—one being enrollment. “St. Paul is the birthplace of public charter schools, so there are choices here,” he says. “There are about 20,000 school-aged children in the city who do not attend Saint Paul Public Schools, and a large percentage of them attend public charter schools.” To this day, one of Gothard’s primary concerns is making sure SPPS is a place any student can call home.

Innovating for the WINN

As he looks back on his time in St. Paul so far, a few key victories stand out in Gothard’s mind. One of these successes began to take shape during a time of deep hardship: the COVID-19 pandemic. In November 2021, SPPS received more than $200 million in ESSER funds thanks to the American Rescue Plan. “Our systems were not built to take in that kind of money,” Gothard says. “We were not going to be able to do with that money what we’d always done—so there was an opportunity to do things differently.”

For Gothard, “different” meant creating an Innovation Office at SPPS, “a brand-new team with new eyes, new procedures, new protocols,” he explains. “This team of specialists could implement strategies, measure them, and report our successes back to the community.”

Now, the Innovation Office oversees more than 50 strategic initiatives aimed at addressing long-term outcomes for SPPS students. Each aligns to one of the six focus areas outlined in the district’s strategic plan, from “Systemic Equity” to “Safe Schools.” “We have project charters. We have teams that monitor progress. We have teams that are meeting and reviewing data cycles,” Gothard explains. “Through the Innovation Office, we’re determining whether or not our funding is meeting the goals of the various initiatives.”

Perhaps the most successful of these initiatives is their science of reading program, WINN—short for “What I Need Now.” Like so many districts nationwide, SPPS saw dramatic drops in state reading test scores during and following the pandemic; in 2022, 50% of the district’s students saw declines in reading scores or remained below grade level.

So the district has pulled together a cohort of 72 educators with expertise in reading instruction. These WINN teachers join every reading class in the district to provide support for students who need it—all during their regular class time. This way, classroom teachers get a little extra help, and students don’t have to be pulled out of class for reading intervention. “You wouldn’t even know during flexible reading groups that some students are receiving extra support from a teacher,” says Gothard. “That makes me feel so good from an equity lens, because our students aren’t stigmatized, and they’re not missing the social interactions that their peers are having.” As a result, 20% of the district’s early grade students are getting reading help through WINN.

But even more unique than the district’s reading program is the accountability plan created by their Innovation Office. Through a public dashboard on the SPPS website, anyone can easily see how much funding the district is allocating to each strategic initiative—including WINN—and how successful they’ve been so far. This doesn’t just hold the district accountable for how it spends its money; it also allows SPPS to make changes in response to data. “We’re making real-time decisions to either add to, support, or stop those initiatives,” says Gothard. “It’s been really effective.”

So is WINN actually working? The data says yes. According to scores from the 2021-22 school year, WINN students—especially second and third graders—are showing great progress. Gothard has seen this growth firsthand, observing in classrooms and reading with students himself. “It’s one of the most successful strategies I’ve seen in my career,” he says. “It’s one of the things I’m most proud of.”

Thanks to this data, SPPS will have great justification for continuing to fund WINN work even after ESSER funds run out in September 2024. “This is working,” says Gothard. “And because of the progress monitoring that they’ve been able to do, I can say to our board and our community, We’re going to continue this strategy, and here’s why. Here’s the data that supports it.”

A Place of Pride

Another highlight of Gothard’s career at SPPS came just a few months ago, with the opening of the district’s brand-new East African Elementary Magnet School. The school, open to grades pre-K through fifth, incorporates the diverse cultures and languages of the East African diaspora into its regular instruction. It’s the first of its kind in the nation.

Why an East African school? “We listened to our families when they said what they wanted for their children,” Gothard says. “Through our research, we understood that there were enough families in St. Paul who wanted this type of educational experience.”

About 7.5% of St. Paul students are of East African descent—but many families had been leaving the district for charter schools that catered to their specific cultures, contributing to declining enrollment. “I want our school district to be the destination choice for families in our area,” says Gothard. “It’s a shame that families would have to hop on a bus and go across town—or even leave our city—for an experience that we could offer right here.”

For months, a task force made up of staff and community members had been discussing the possibility of opening an East African school, and in 2023, the time seemed right. Low enrollment had forced SPPS to close or merge a few schools, leaving multiple buildings empty. Plus, the district’s own research indicated that the audience for such a school existed. “We identified the right leader,” Gothard says—Dr. Abdisalam Adam, a 27-year veteran of SPPS and a prominent leader in the Somali community. Teachers who’d served on the task force were ready and willing to join the new school’s staff, and families were enthusiastic about the idea. “It became really clear to me that we were ready for the school,” says Gothard.

At the start of the 2023-24 school year, the East African Elementary Magnet School opened its doors to 260 kids—a number that exceeded the school’s initial enrollment goal. About 80% of those children attended a school outside of SPPS the year before. The promise of the school drew them in, but it’s the experience within its walls that will determine whether they stay.

That experience hinges not just on academic rigor, but on the school’s understanding and celebration of the distinct cultures of its students. “It’s incredibly diverse,” Gothard says. “Sometimes we get such a narrow perspective of what a region means, but from language to customs, there’s a lot of different cultures within the East African community.” The magnet school focuses on the cultures of nine countries—Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia, Sudan, South Sudan, Tanzania, and Uganda—as well as six East African languages.

And the school’s students see themselves reflected in more than just the curriculum. While the staff is diverse overall, about one-third are East African. All those years ago, Gothard saw something of himself in Ms. Bell; now, these students will see themselves in their teachers.

“The East African school is open to any student,” Gothard clarifies. “A student does not have to be of East African descent to attend. But we wanted to create a place of pride for our East African families, where they could come together and see their children learning their languages and cultures as part of their school experience.” In other words, a place where students and their families could feel at home.

Leading and Listening

When asked about his leadership style, Gothard replies imply, “I’m a good listener.” Never content to rest on his laurels, the superintendent is constantly trying to deepen his understanding of what SPPS students need—and that means listening.

Last spring, following an emergency at one of the district’s high schools, Gothard decided to convene a meeting with ninth through twelfth graders from across the district. “For nine full days, we bussed students to a community center here in the city, and I spent the entire day engaged with them,” he says. “It was by far the most beneficial thing I ever did.”

Given the context, Gothard expected to mainly hear his students’ safety concerns. “And safety came up, don’t get me wrong,” he says. “But their experiences as students, as individuals, as a community came up far more. Students wanted to be heard. They wanted me to know what their days are like, what they’re facing, what they experience, what they’d like to see in their schools.”

The conversations were, in a word, eye-opening. “It was really the researcher and the human in me connecting with our students, trying to understand how I can ensure that the experiences we’re offering are what they need,” he says.

This has been the through line of Gothard’s three decades in education—meeting needs, improving experiences, making SPPS a place students can call home. Ms. Bell gave him that, and now he’s paying it forward. “There’s nothing like a school community that can really see all of its students,” he says. And in St. Paul, that’s exactly the kind of community he’s building.

Subscribe below to stay connected with SchoolCEO!